When you’re nearly 40 and unmarried, and you realize you’re going to be okay.

A few weeks ago my best friend’s nine-year-old daughter and I were playing. Our play consists of her sometimes weaving pink ribbons through my hair or me helping her assemble an imaginary set for a show she’s intent on producing (she’s creative, this one). That day, after I affixed one of the many glittery crowns she owned on her head, she asked, Are you ever going to have children, Felicia? I admired her moxie, the way in which she’s able to navigate terrain that one could consider a minefield. Adults exercise politeness and discretion in a way that can sometimes be numbing, and it was such an odd relief to hear a child ask something so plainly–just because I’m the only woman she knows who doesn’t have a child of her own. My best friend and I exchanged a look, and I replied, No, C. I don’t plan on having children. She appeared pensive, and after a few moments she nodded her head, said, okay, and we continued on with our play.

I did love, once. Yet it was love that was easily altered, one that had slowly come apart at the seams. But for a time we lived a terrific photograph, and spoke of glinting diamonds, me swanning about in a white dress and children winding around my calves. This life, while part of a defined plan I had for myself, felt distant, foreign–an uninhabited country for which I needed a visa and complicated paperwork for entry. I never took to the idea of being owned by someone else; I never considered changing my name. I never imagined myself in a white dress (I prefer blue), and I’ve never truly felt the maternal ache and tug as many of my dear friends who are mothers, describe. Back then I viewed marriage as less of a partnership and more of a prison, but I imagine that had much to do with the man in my life. Back then I slept on top sheets rather than between them, and I was forever poised for flight. Back then I didn’t want children because I was certain I wouldn’t be any good at it considering my history.

After a couple of years of playing house, this great love and I experienced a drift and while he went on to marry and have a family of his own, I never once thought I’d missed out on my chance, rather, I was relieved. I treasure my solitude, my freedom. I didn’t want to be harvested. Back then I had so much work ahead of me, work on my self, my character, that I knew I wouldn’t be much good to anyone else. I knew I had to make myself whole and complete before I gave even a sliver of myself to someone else.

“I believe I know the only cure, which is to make one’s center of life inside of one’s self.” — Edith Wharton

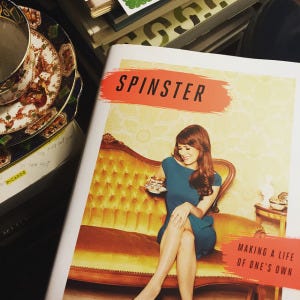

I came across Kate Bolick’s Spinster not from her widely-read Atlantic essay (I miss out on everything), but serendipitously through a Times book review. I nodded along with Bolick, and found her to be an “awakener” (a riff off Kate Chopin’s The Awakening), much like the ones she describes in her book. Over the past few years I’ve been so consumed with cultivating a good life, in living through the questions, in being a sponge when it comes to knowledge and culture, that I hadn’t stopped, not even for a moment, to consider the fact that I’m in my late 30s and am still not married. I’ve witnessed scores of my friends fall in love, marry, bear children, and I feel joy for them, rather than envy. And I’m also privy to the unseemly side of coupling–of people who talk about being incomplete without having a partner, people who feel like a failure because they haven’t fulfilled a role ascribed to them, and my heart breaks because no one person will ever complete you. It doesn’t work that way. You’ve got to come into the game, whole; you’ve got to hold your own cards, be willing to play your own hand.

It doesn’t make sense to come to the table with a few cards rather than a deck.

Nearly all my friends my age are married–most, happily so. Acquaintances congratulate engagements and pregnancy announcements with a welcome to the club message, as if these points in time gain you access to some sort of privileged society, which rings odd and exclusionary, at best. I don’t view marriage, or the decision to have children, as checks in a box or private clubs where one is finally granted trespass, rather I think of them as individual choices we make. We meet a great love and decide to marry, or not. We meet a great love and decide to have children, or not. We never meet a great love and the world as we know has yet to collapse. Or, perhaps, we don’t make love a vocation. Maybe we just live our best lives and play out the hand.

“She was the only one of the lot of them who hadn’t gone off and got married. She had never wanted to assert herself like that, never needed to.” — Maeve Brennan

It occurs to me that I’m not certain I’ll ever get married, and I’m okay with that. While I like the idea of a partner, a companion, someone with whom I’m besotted, somehow the vision of me in a dress surrounded by people applauding me down an aisle makes me cringe. The idea of me trading one man’s name for another feels false (I’ll keep Sullivan, thank you). And I’ve come to realize that I’m a better friend, sister, and lover because I choose not to have children.

All I want to do right now is create, to see everything that hasn’t been seen. To know what I don’t know. And if in that journey I meet someone, cool. However, if I don’t, that’s cool too.