Every morning at 7 a.m., Matt Mullenweg wakes up in Houston, Texas, and reads a book. After a chapter or so, he scrambles some eggs, grabs a couple bottles of Hint water, and wanders over to his office—a desk a few feet away. This is the executive suite from which Mullenweg runs his three companies, a venture-backed startup, a nonprofit foundation, and one of the world’s largest open source projects.

He logs into the internal project room where team members post discussions about what they’re doing. It’s buzzing with hundreds of updates from employees working from their homes in Europe, Asia, Australia, and the East Coast. Most of them only see each other once or twice a year.

Mullenweg turns on some jazz and starts reading. There will be no formal meetings today, or on any day this month. And only rarely does anyone communicate using email. He keeps his Skype connection open in case anyone wants to chat one-on-one while he trolls the discussions—which continue to update in almost real time.

In one of the posts, Mullenweg notices something out of sync and starts typing. Twenty seconds and 30 words later, he punches the “Post it” button. The pattern continues for the next several hours. A programmer is not thinking holistically about a particular feature. A team is getting off track from the broader product vision. On the side, he chats with a dozen people about how they’re feeling, and touches base with a few key employees. Course corrected.

Then he closes his web browser and goes to dinner.

And that is how Mullenweg, creator of WordPress, founder of Automattic, and chairman of The WordPress Foundation, runs 22% of the Internet.

Every second, somewhere in the world four babies and two WordPress blogs are born. When those babies are old enough to blog, Facebook might not be the dominant social network anymore. But WordPress, the 11-year-old open source blog software, might just be their publishing platform.

One-fifth of all websites currently use WordPress. Facebook, by comparison, consumes the lives of about a third of Internet users. But while Facebook has 6,818 employees, WordPress is run by just 230 people. Facebook is valued at around $150 billion. Mullenweg this year closed a $160 million investment round for his WordPress hosting company, Automattic. He plans on using the money to increase the size of his staff, to 2,000 people.

Every day, Automattic’s nine data centers push an astronomical 450 terabytes of data around the globe. (The much-anticipated WordPress Version 4.0 just launched on Friday, with millions of downloads already.) However, “I think we can do four times what we are now,” Matt Mullenweg, recently told Fast Company. “Seventy or eighty percent of the web.”

Yet even at that scale, Mullenweg is committed to continue running the WordPress ecosystem as a bizarre blend of non- and for-profit, meritocracy, and dictatorship. At the helm sits Mullenweg, playing “jazz director” and preaching open source, while carefully puppeteering every detail of his organization.

When management guru Scott Berkun “showed up to work” at Automattic in 2010, he worried that what made him good at other jobs wouldn’t transfer to the chaotic, impersonal coworking dynamic for which Automattic was famous. “My best leadership tricks depended on being in the same room with people,” he wrote. He wanted to know how such a successful enterprise had grown without emails or meetings or managers, and if it could continue to grow that way.

“At times I felt like a capitalist in a socialist country,” said Berkun, who spent an ethnographic 18 months inside of WordPress and wrote a book about the company’s unique culture, called The Year Without Pants, which was released last September.

By the time he arrived, WordPress had become the web’s dominant blogging and content management platform. At around 60 employees, the company finally added some structure: The company split into a dozen small teams to work on individual projects together. Berkun joined the “social media” product team.

He quickly discovered that the famous Automattic chaos was actually quite organized. People had confused cultural freedom with disorganization, but to the contrary, Mullenweg had created a highly efficient process. Hours on the clock, employee location, managers—Mullenweg’s philosophy was that these kinds of things were moot if the work itself got done, and that most companies engaged in a lot of unnecessary “metawork” because of these. He believed that if you removed those things, along with efficiency-destroying interruptions like email and phone calls and meetings, work could proceed more quickly and with less pain.

And though it sounds crazy, he replaced all of those things with one simple thing: blog posts.

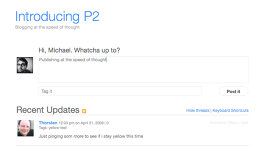

Automattic’s secret sauce is a WordPress theme called P2 that every employee publishes posts on all day long. At the top of a P2 blog post is a blank box. When you enter something and hit submit, your update appears in a list below, essentially forming a big, group comment thread. Each P2 post gets its own URL, which can be referenced in other posts. Every project, question, idea, complaint, and conversation gets its own P2, and anyone who wants to can participate.

There are no private P2s. Everyone, from intern to CEO, can weigh in on anything. Most people aren’t interested in most posts, of course, but if ever someone at Automattic needs to know about something—in any project and from any point in history—a P2 record is there.

Each Automattic employee checks the P2s all day long. Instead of email, which decays over time and empowers the sender, P2s are permanent and empower the group.

The radically transparent P2 method virtually eliminates politics. It keeps remote employees in the loop on everything in the company—it’s their fault if you don’t know about something, because that means you haven’t read. The P2 system encourages healthy debate (which happens often), and reinforces the idea of meritocracy. Automattic also tracks employees’ actual work (support tickets closed, code written and deleted) and puts it on a public scoreboard, so everyone knows how everyone else is doing. This creates internal pressure to achieve results and avoid that dreaded metawork.

Though the system does have downsides (some conversations need to be real-time and involve fewer people, threads can be hijacked by tangents, and blog posts lack visual data like tone and body language), Berkun came to believe that the P2 method rendered Automattic’s product development process and remote organization rather shatterproof. “It’s very resilient, just not in the same predictable way that classical management or engineering would define resilience,” Berkun explains. “It seems completely insane. But if you have smart people that you’re working with it’s actually liberating.”

When forced to publicly document everything, the disparate team members became that jazz ensemble, each player improvising his or her own notes, but making music without skipping beats. (Automattic embraces the analogy by naming its product releases after jazz musicians.)

The great irony in this, of course, is Mullenweg himself. In the jazz ensemble, Mullenweg’s notes overrode everything. “I’m married to WordPress,” he told me. All the high-stakes decisions for all three organizations were made by him—and often low-stakes ones as well. Employees jokingly referred to the following common occurrence as “Matt bombing,” writes Berkun:

“This was when a team was working on something in a P2, heading in one direction. Then late in the thread, often at a point where some people felt there was already rough consensus, Matt would drop in, leave a comment advocating a different direction, and then disappear.”

On the P2 boards, the personally charismatic founder who friends variously describe to me as “calm,” “wise,” and a “gentleman,” recalls Berkun, “earned a reputation for being terse, occasionally cryptic, and, to some, quite intimidating online.”

Yet it worked. WordPress kept growing. And Automattic employees were happy.

As product visionary, Mullenweg was able to use P2s to scale himself beyond the effectiveness of a typical manager.

“If I were just dropping into a meeting like a regular manager, I would only have a few minutes of context,” Mullenweg explains. “With the P2 structure, I can read [about] everything leading up to it and get a deep context.” Instead of delegation, he simply had to be good at reading.

Mullenweg thinks his unconventional management system should be adopted by businesses everywhere. Still, with 190 employees by the time Berkun’s book was published, it was a wonder Mullenweg had been able to keep micromanaging the Automattic team while running the open source project and the WordPress Foundation.

In truth he did have some help. Toni Schneider, an executive who early Automattic investors brought in as CEO eight years ago, managed business and revenue affairs while Mullenweg did his jazz-product thing.

That is, until January when Schneider stepped down.

Back in 2005, it became clear that WordPress couldn’t be supported at scale through the generosity of starving programmers alone. Security and infrastructure would become increasingly disaster-prone as more people used it. Mullenweg believed fanatically that software should be free, and he created a for-profit side to WordPress to solve that problem. “Nonprofits can do amazing things but their reach is often limited; for-profits often do amazing things, but often their vision is limited,” he says. “I thought if we could take the best of both, a complementary for-profit and nonprofit and create a wider ecosystem, we could create something bigger than them both.”

So, he established Automattic, a corporation that provided web hosting and premium services to WordPress users who wanted the free software but were willing to pay someone else to run it for them. Mullenweg raised $1.1 million in venture capital and brought on Schneider, an experienced CEO who’d sold his webmail service, Oddpost, to Yahoo in 2004 (Oddpost became Yahoo Mail), to take care of business while Mullenweg focused on the product and community. Automattic would use some of its profits to ensure the continued development of the free WordPress code—especially unsexy components like security and infrastructure.

A fuzzy line separated the corporation (wordpress.com, which Automattic claimed) and the open source project (wordpress.org). “There were some people who were involved in the community who wanted to get jobs at Automattic but who were not offered jobs,” said Siobhan McKeown, a WordPress historian who works for Mullenweg’s personal investment company. Plus, she says, “Whenever there’s a media story, they say ‘Automattic, the makers of WordPress,’ and people get frustrated with that.”

Rich Bowen, an early WordPress.org contributor, and several others led a group in 2006 which split off from WordPress’s codebase to form a rival blog tool, Habari—having grievances with Mullenweg’s top-down decisions. “The perception was that people would work hard on patches, and he would accept or reject them in a somewhat capricious manner,” Bowen says.

As if to make things more confusing, Mullenweg also created a 501(c)(3) called the WordPress Foundation, with the mission of democratizing publishing through open source software. Its charge was to protect the WordPress trademark and educate the public about the benefits of open source.

Mullenweg himself made it all work. “Subsequent history has shown that he must have been doing something right,” Bowen admits. Through sheer charisma and micro-management, Mullenweg calmed the community and orchestrated the coders and volunteer educators within boundaries he set. He came to describe himself as a “benevolent dictator,” helming the nonprofit, the open source project, and the commercial product offerings himself. Meanwhile, Habari and other splinter projects floundered, with little resources and direction.

As Automattic’s revenue grew, he recruited work-from-home programmers from various corners of the world with the promise of freedom and flexibility, so long as they followed his process of no meetings and no email, and no hierarchy but “Matt.”

The most important difference between Mullenweg and, say, Mark Zuckerberg is one of philosophy. Mullenweg keeps WordPress open source, because he believes it keeps him honest and shows that his intentions are pure—and that keeps the community building his software for free, despite what some outsiders see as a conflict of interest. “People could pick up [the code] and start their own WordPress,” Mullenweg says. “That’s sort of how it started in the first place.” Despite the dictatorial nature of his management, it’s Mullenweg’s genuineness and vision that keeps WordPress’s contributors contributing, Automattic’s employees from churning.

On the other hand, Facebook’s founder has put business before users enough times to make “we promise not to screw you for 2 years” the big reveal at his recent F8 summit. So if we had to entrust one of the two men with three-fourths of the web, I think a lot of people would pick Mullenweg.

Yet, if Zuckerberg dies, Facebook users won’t notice. If Mullenweg moves on, WordPress won’t immediately crumble, but its spiritual fire may die. No remote work, open-source-based organization in history has grown as big as Automattic intends. But as Berkun points out, “The oldest, largest companies today all began much like Automattic, with ambitious youth, big ideas, and high thresholds for change.” And Mullenweg adds, “I get excited when people say things can’t be done.”

Having been coached by Schneider, Mullenweg may no longer need adult supervision to run his three-headed organization. But despite his remarkable ability to influence and manage unwieldy programmers, Automattic is at a turning point. Mullenweg says he’s ready to be CEO of a big company, and he doesn’t want the distributed team or open source nature of the firm to change. But he admits that he’s going to need good lieutenants and to shift his management style—P2s or no—if he’s to get to 2,000 employees.

Last September, I asked him, “What if I offered you, personally, a billion dollars right now to sell me WordPress?” He laughed. “I would say I’m very flattered, but we have a lot of work left to do.”

Shane Snow is the author of Smartcuts: How Hackers, Innovators, and Icons Accelerate Success.