Is Scurvy The New Diabetes? — Matter — Medium

Right now, there’s about a cup of orange juice in my gut, sloshing around and mingling with my stomach acid as it delivers all the vitamin C that I require for the day. I’ve got some major bruises on my knees, and so once the essential nutrient hits my body’s internal transport system, the orange juice that I just drank will play an important role in wound healing, preventing future capillaries from bleeding too easily, and with any luck helping me perform enough sweet, sweet collagen synthesis to make it look like I sleep regularly. Vitamin C may be the most important water-soluble antioxidant in human plasma, and is required for all plants and animals. But while most other animals can synthesize their own supply, humans — along with other primates, guinea pigs, capybaras, some fish, and some bats — have to get theirs elsewhere. Hence the orange juice.

The problem is that not everyone gets enough. And when vitamin C goes missing from a diet for long enough, the results can be explicitly unpleasant: scurvy.

We act like scurvy is long left behind, a throwback disease, forgotten and dust-covered and banished to antiquity. But this scourge of sailors is, in fact, not something that humanity has outgrown. It still happens, and probably more than you realize.

Scurvy, the most extreme result of prolonged lack of vitamin C, is, in a word, unpleasant. In three, it’s “fatal if untreated.” The disease kicks off with the universal symptoms of “ugh”: low-grade inflammation, fatigue, bleeding gums, and swollen joints. Vitamin C is absolutely necessary for healthy collagen, which matters greatly because it makes up one fourth to one third of all of the protein that makes up you. It’s in your skin, your tendons, your bones, your gut, and your blood vessels, just to name a few. Your body is forever making more of it, knitting yourself together with a kind of sticky meat yarn. Without enough vitamin C, the collagen is made poorly and is therefore unstable: capillaries burst, wounds remain open, and, since your body is constantly replacing the collagen in scar tissue, old scars can reopen. As the owner of a C-section scar, I find this possibility very distressing.

If you think of your body like a car or a building, collagen is doing a hell of a lot of the upkeep. But no vitamin C means no collagen, means no upkeep, means open, suppurating sores that will never heal, means the kind of sores that do not smell okay. Scurvy can also loosen the teeth, which is a literal nightmare I have at least twice a year.

A diet devoid of vitamin C is always fatal, if left untreated; without it, you basically just fall apart because your body can’t make the collagen that keeps you glued together.

The exact details of scurvy eluded explorers for centuries. It was hard to keep a boat full of sailors alive at sea by feeding them stale carbs, salted meat, and booze, but then again, it was pretty hard to keep a boat full of sailors alive in general. Of course, just because humans didn’t always fully understand the disease doesn’t mean they weren’t on the case. People had their suspicions regarding the correlation between the lack of fresh foods and withering sailors for centuries. By the late 1400s, the healing powers of citrus were known, but it wouldn’t be until the mid-18th century that medicine gave us definitive answers. In what is famously known as the first clinical trial ever (owing to his use of control groups), ship surgeon James Lind formally concluded that scurvy could be cured by citrus fruits, debunking the popular theory that it was caused by a lack of acids. Lind, however, waited to inform the British Navy about his findings because of citrus’s high price; it would be nearly 50 years before lemon juice would become a required ration in the Navy.

Yes, yes, but what does this have to do with me?

It’s true: Scurvy is not something that you will readily encounter in mainstream American life, since death from lack of vitamin C requires poor medical care and consistent and prolonged lack of access to fresh or fortified foods. It also often involves a cofactor such as alcoholism, being an elderly shut-in, or inadequate infant nutrition. But that doesn’t mean you’re off the hook: Like so many diseases with social roots, scurvy doesn’t come on like flipping a switch; it’s not as if one day you’re fine, and the next all your old scars are opening up and your tongue is covered in sores. This kind of malnutritive illness exists on a sliding scale of grays. Vitamin C deficiency is no joke, and acting like we don’t have to worry about historical diseases is arrogant and stupid. Here’s why.

There’s a trap that we fall into in our ostensibly affluent country, a mirage flanked by skyrocketing obesity trends on one hand, and our obsession with image on the other. It tells us that in the land of plenty — one of the wealthiest and fattest countries on this blue, agrarian marble — there is no hunger, no malnutrition. How could anyone see our supermarkets and think that children go hungry on the weekends without school lunch? How could they understand bones softened by rickets, or that scurvy is still making gums bleed? Like keeping a lucky rabbit’s foot with your keys, we delude ourselves into thinking that proximity to medical care and healthy food is enough to keep us all well.

But hunger and poverty are quiet monsters, the ones content to burden its victims with the job of concealment. As far as society is concerned, it’s easy to miss what you didn’t want to see in the first place. But in 2013, 49.1 million Americans were food insecure — a status defined by the USDA as “a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food” — and homes with children were more likely to struggle. That year, almost one in five homes with children were food insecure; for households run by a single mother, the rate jumped to over 1 in 3.

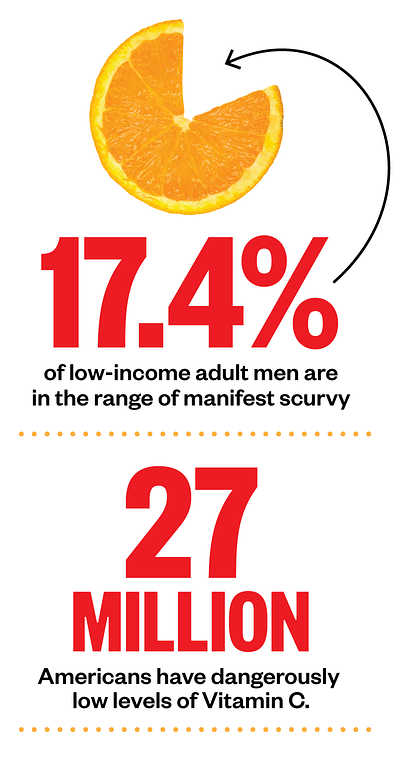

The last time CDC researchers looked at vitamin C deficiency among the American public, they found that an estimated 8.4 percent of adults aged 20 and older were at risk of developing scurvy. Like scurvy-scurvy, with wound-healing problems and weird rashes and bleeding gums, the whole sick-pirate bit. Prolonged vitamin C levels this low are incredibly dangerous.

But it’s not just scurvy-scurvy, either. There’s also latent scurvy, which happens when vitamin C concentrations are low but not super low. Research suggests it’s associated with fatigue and irritability, as well as vague, dull, aching pains; one study showed 15.7 percent of adults had vitamin C levels in this low range.

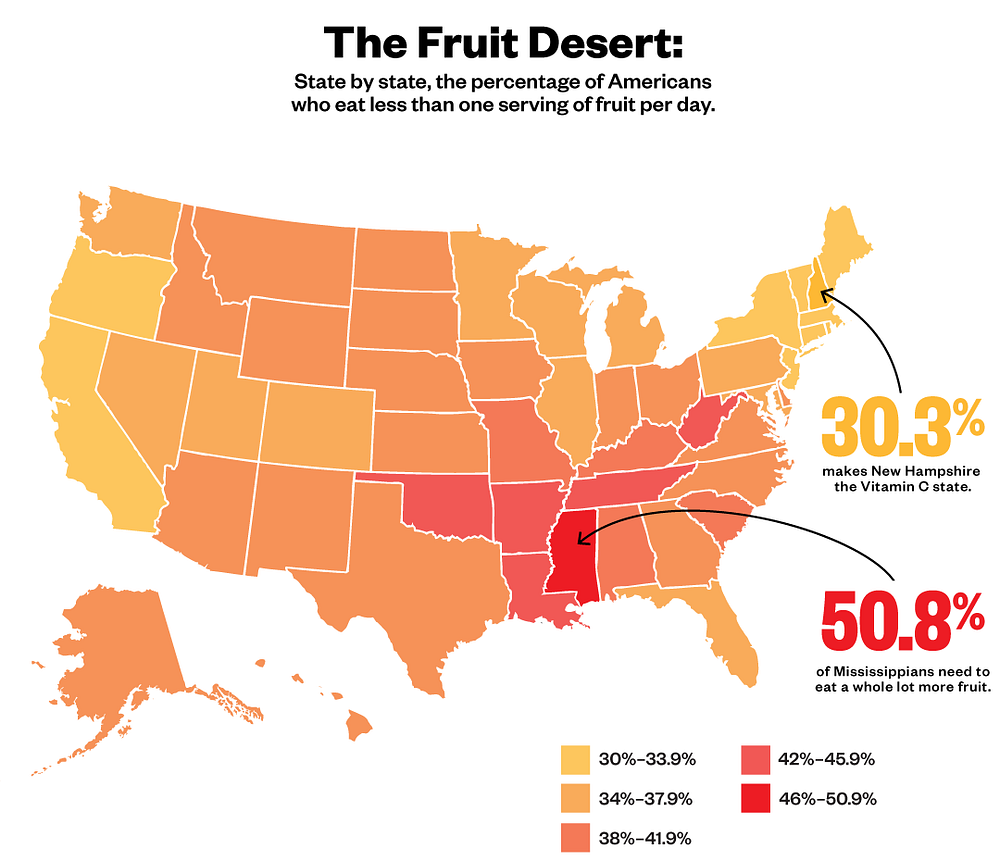

There is good news, however. Vitamin C levels are actually going up. In the late 1980s and early ’90s, the overall prevalence of deficiency was much higher — it had halved a decade later, and continued to fall. But the dramatic decrease is not for the reasons you may think. There was, in fact, no uptick in fruit and vegetable intake over that time: Consumption held steady for fruit at 1.6 servings a day on average, while for vegetables it dropped slightly, from 3.4 to 3.2. We’re actually eating just a little bit worse than we used to. But at the same time there was a decrease in smoking, and smoking makes it harder to properly absorb vitamin C.

The rest of the news is, unfortunately, bad.

Perhaps most distressing is the clear influence of socioeconomic status. The study found that the average vitamin C concentrations increase, and prevalence of vitamin C deficiency decrease, with improving socioeconomic circumstances. Of the men in the lowest bracket, 17.4 percent were deficient and in the range for developing scurvy, but on the other end of the spectrum, males with high socioeconomic status clocked in at a mere 7.9 percent. The same trend is apparent in women, whose rate of vitamin C deficiency drops from one in 10 in the lower income bracket to one in 20 in the high.

The way we eat now versus the way we ate then has long inspired dieting fads — just think paleo — but you cannot pin scurvy on the advent of processed food. It’s true that cooking, canning, and other forms of preservation can and do degrade the amount of vitamin C present, but many food manufacturers add it (under the name ascorbic acid) as a preservative. And with the ubiquity of enriched beverages and “immune-boosting supplements,” it’s not as if the nutrient is hard to find.

Even so, with one in three single-mother households dealing with food insecurity, and one in 10 women with diminished socioeconomic status verifiably in the scurvy zone when it comes to vitamin C levels, it’s clear that there is a failure of the system.

Like Type 2 diabetes, scurvy is well-known, diet-related and just as avoidable — even if it may never be as widespread or as omnipresent.

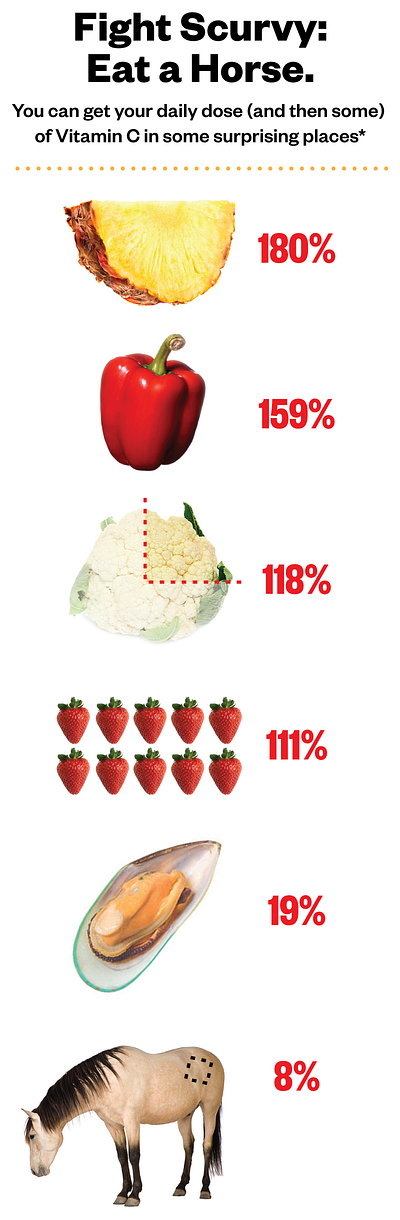

As hard as it may be to believe, a significant proportion of the U.S. population is at risk. Huge swaths of the populace are unknowingly flirting with scurvy — and yet the treatment is incredibly simple: Consuming vitamin C–rich foods like brightly colored fresh fruits and vegetables, oysters, or even (as soldiers in Napoleon’s army discovered) fresh horse meat is enough to treat the disease. But treatment is easy; the solution is hard.

Scurvy isn’t malevolent; it is merely the poster child for a broken social contract. The kind where the wealth gap widens and people are slipping deeper into poverty as the federal government cuts $93 million in spending to Women, Infants and Children — a program offering nutritional support to low-income women and their kids. Combine that with the fact that processed foods are cheap and filling, and suddenly vitamin C levels in the scurvy zone start to make more sense.

We worry so much about the illnesses we pass on to each other: Measles, ebola, all the rest. But what do we do when sickness isn’t spread by germy fingers, but by apathy?

A portion of the research for this series was crowdfunded on Inkshares.

Read more Revival of the Sickest

Follow Matter on Twitter | Like us on Facebook | Subscribe to our newsletter