Daniel Bachhuber: A mile wide, an inch deep http://t.co/afsX6sHH3X

A mile wide, an inch deep

I was recently quoted as saying, “I don’t give a shit” if Instagram has more users than Twitter. If you read the article you’ll note there’s a big “if” before my not giving of said shit. As quoted:

If you think about the impact Twitter has on the world versus Instagram, it’s pretty significant. It’s at least apples to oranges. Twitter is what we wanted it to be. It’s this realtime information network where everything in the world that happens on Twitter — important stuff breaks on Twitter and world leaders have conversations on Twitter. If that’s happening, I frankly don’t give a shit if Instagram has more people looking at pretty pictures.

Of course, I am trivializing what Instagram is to many people. It’s a beautifully executed app that enables the creation and enjoyment of art, as well as human connection, which is often a good thing. But my rant had very little to do with it (or with Twitter). My rant was the result of increasing frustration with the one-dimensionality that those who report on, invest in, and build consumer Internet services talk about success.

Ask any junior high student which rectangle is bigger, one that is three inches wide or one that is two-and-a-half inches wide, and they’ll tell you it’s a nonsensical question unless they have more information — specifically, the height.

And yet, we literally say one company or service is “bigger” based on a single number — specifically, number of people who have “used” it in the last 30 days. Even without getting into how “use” is defined, this is dumb.

In the recent Instagram/Twitter case, Will Oremus’s piece in Slate is the one I saw that didn’t just regurgitate the “bigger” headline. He does a great job of explaining why it’s not that simple. It’s worth a read, but the summary is this:

So is Instagram larger than Twitter? No — it’s different than Twitter. One is largely private, the other largely public. One focuses on photos, the other on ideas. They’re both very large, and they’re both growing.

Medium had its biggest week ever last week — or so we might claim. By number of unique visitors to medium.com, we blew it out of the park. The main driver was a highly viral post that blew up (mostly on Facebook). However, the vast majority of those visitors stayed a fraction of what our average visitor stays, and they read hardly anything.

That’s why, internally, our top-line metric is “TTR,” which stands for total time reading. It’s an imperfect measure of time people spend on story pages. We think this is a better estimate of whether people are actually getting value out of Medium. By TTR, last week was still big, but we had 50% more TTR during a week in early October when we had 60% as many unique visitors (i.e., there was way more actual reading per visit).

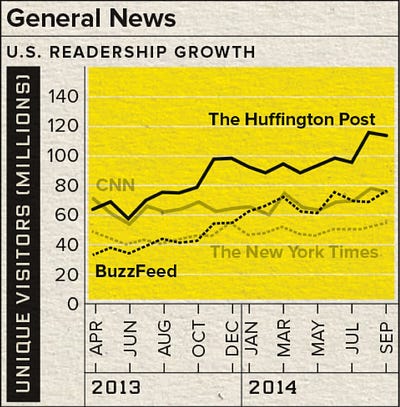

Mat Honan’s excellent Wired article about the state of new media today accurately points out that everyone is in a “war for attention.” But it uses unique visitors as the way to compare how different outlets are doing in this war:

By this metric (misleadingly labeled “readership”), Buzzfeed is “bigger” than The New York Times. But that’s the exact same metric that would tell us last week was bigger for Medium than that week in October. Even if all we care about is attention — not any other value that may be important— this doesn’t tell us much. Maybe BuzzFeed gets more attention, total, than The Times. But we should stop purporting that one-dimensional graphs like this tell us that.

More grains of salt: The chart above — and a lot of the comparisons you read in the press about web site traffic — are based on Comscore’s numbers and only count U.S. users. Two big problems with this: 1) Most site operators will tell you their numbers vary greatly from Comscore’s. The smaller a site is, the more likely this is true (due to their sampling method). Although, Comscore will tell you that’s because they filter out duplicate users. 2) A small portion of total Internet users are in the U.S. Every site is global — but to very different degrees. So without a disclaimer that we’re only interested in the U.S., only showing U.S. numbers could be highly misleading.

Lastly, it’s not clear whether Comscore’s numbers include app traffic. I know they track app usage to some extent, but are they counting all of NYT’s apps in the above chart (or Buzzfeed’s)? (Leave a note here if you know.)

We pay more attention to time spent reading than number of visitors at Medium because, in a world of infinite content — where there are a million shiny attention-grabbing objects a touch away and notifications coming in constantly — it’s meaningful when someone is actually spending time. After all, for a currency to be valuable, it has to be scarce. And while the amount of attention people are willing to give to media and the Internet in general has skyrocketed — largely due to having a screen and connection with them everywhere — it eventually is finite.

We’re not alone in this view. Chartbeat’s Tony Haile has done a great job of promoting the idea of an “Attention Web” (as opposed to the “Click Web”). He’s hopeful a shift to measuring attention will improve the web:

For quality publishers, valuing ads not simply on clicks but on the time and attention they accrue might just be the lifeline they’ve been looking for. Time is a rare scarce resource on the web and we spend more of our time with good content than with bad. Valuing advertising on time and attention means that publishers of great content can charge more for their ads than those who create link bait.

We love thinking this way because it rewards us for sharing content that people really enjoy and find valuable — not just stuff they click on a lot. It may mean that we don’t do quite as well on uniques or pageviews, but that’s a tradeoff we’re happy to make because this is a metric focused on real user satisfaction.

And in that Wired article, they mention why time is more valuable if you’re in the ad business:

Your clicks are valuable, and your eyeballs are valuable, but to advertisers your time is the most precious commodity of all — and publishers say they want to sell ads based on the time readers spend on their sites, not mere pageviews. So, the logic goes, the more time you spent with a story, the more expensive the accompanying ads would be.

The problem with time, though, is it’s not actually measuring value. It’s measuring cost as a proxy for value.

Advertisers don’t really want your time — they want to make an impression on your mind, consciously or subconsciously (and, ultimately, your money).

As the writer of this piece, I don’t really want your time — I want to make an impression on how you think. If my rhetorical skills let me do that in less time (for me and you), all the better.

At Medium, we don’t really want anyone’s time. We want to create a platform that enables people to make an impression on others. To make them think. To change their minds. To teach them something or connect emotionally. It’s hard to measure any of that.

What if there was some new genre or form or author on Medium that was incredibly addictive and popular but, to our minds, didn’t seem of significant value or lasting import? The soap opera or Farmville of Medium posts, let’s say. Our TTR charts would probably go through the roof, and we’d have the illusion of success and be happy. But taking people’s time isn’t really the goal. And people wasting time is actually the opposite of the goal.

This is the problem with any one-dimensional metric. As Jonah Peretti says, there’s no “God metric”:

I feel like what you see in the industry now is people jumping around and trying to find the God metric for content. It’s all about shares or it’s all about time spent or it’s all about pages or it’s all about uniques. The problem is you can only optimize one thing and you have to pick, otherwise all you’re doing is making a bunch of compromises if you try to optimize for multiple things.

In the early days at Google, I remember the (crayon) chart on the wall was number of queries. This seemed like a very sensible measure of value. And, in fact, there was an emphasis on taking as little of people’s time as possible. If your service is a utility, as opposed to media, that’s probably a good goal.

(Twitter is as much utility as media and part of its benefit is being incredibly concise — plus, a lot of its purpose, like Google, is to point people off to other places. So optimizing for time spent probably wouldn’t make sense.)

If you look at the other best tech company there is — Apple — it’s also clear they are not optimizing for number of people using their products. While network effects (and revenue) mean that they clearly care about that, they’ve built the most valuable company on the planet by focusing on building the best product possible — in fact, one of their strategies is building an integrated set of products and selling as many of them as possible to the same user (at a healthy margin).

There are other historical lessons in the many companies that were lauded for their meteoric rise in user counts (and resulting valuations), most of which came crashing back to Earth.

Most Internet companies would build better things and create more value if they paid more attention to depth than breadth.

There was a time, in fact, when that was more the case. In earlier web times page views were talked about at least as much as unique visitors. But that became obsolete and meaningless (as “hits” had before that) even before the rise of apps made that abundantly clear.

In 2006, I wrote a blog post pointing this out.

While page views just became silly, for technical reasons, the MAU/UV emphasis feels toxic.

If what you care about — or are trying to report on — is impact on the world, it all gets very slippery. You’re not measuring a rectangle, you’re measuring a multi-dimensional space. You have to accept that things are very imperfectly measured and just try to learn as much as you can from multiple metrics and anecdotes.

If you’re trying to measure the value of a company, it’s in theory a lot simpler. The value of a company, from a financial perspective, is its ability to make money over time. This is not easy, and growth trajectory matters a lot for new companies. But what’s amazing — despite the contrary examples of Google and Apple — is that Wall Street has seemed to buy into the users = value equation. That, of course, trickles down to the valuations of private companies and the obsessions of VCs and the tech press.

If you’re an entrepreneur (or public company employee), don’t get caught up in this.

Numbers are important. Number of users is important. So are lots of other things. Different services create value in different ways. Trust your gut as much (or more) than the numbers. Figure out what matters and build something good.