The Nazis Obsessed Over Beauty — War Is Boring — Medium

It’s footage from German Arts Day—in 1939. A march in celebration of the Nazi aesthetic.

“The government—half of which consists of men who once aspired to serve the arts—is conscious of the artist’s role as an intermediary,” the narrator says, quoting famed Nazi literati Hans-Friedrich Blunck.

“This government … knows the people’s inner longings, their boundless dreams, to which only the artist can give form.”

The footage plays at the beginning of Architecture of Doom, a 1989 Swedish documentary from writer-director Peter Cohen that explores Hitler’s idea of beauty—and the terrible things he would do to realize it.

Nazis are one of popular culture’s most enduring villains. In video games, T.V. shows and movies, no one much cares if the heroes kill Nazis. It’s a trope that’s endured for half a century.

It’s not hard to understand why. The Nazis slaughtered millions of people.

But Stalin and his regime also killed millions … and yet the Soviets don’t usually warrant the same depiction that the Nazis do.

It’s all in the presentation. Nazis were slick. They wore black and red. Skulls on their uniforms. They called their regime the Third Reich, invoking a long-dead age of Roman conquerors.

Nazis are our favorite bad guys because they look like bad guys. A look they chose for themselves.

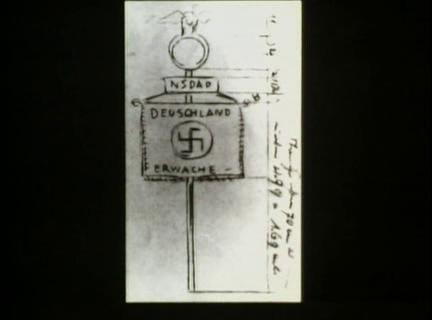

A black swastika on a red field doesn’t need Nazi atrocities to be evocative. Which is exactly what Hitler wanted. He was a failed artist with a powerful imagination … and an ego to match.

“Failed artists were characteristic of the leadership of the Third Reich,” Cohen explains in Architecture of Doom.

The Academy of Fine Arts Vienna twice rejected Hitler’s application. Propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels wrote a novel, poems and plays. Baldur Von Schirach—head of the Hitler Youth—penned poetry. Alfred Rosenberg, a Nazi who held many positions in the party, painted and longed to write a book.

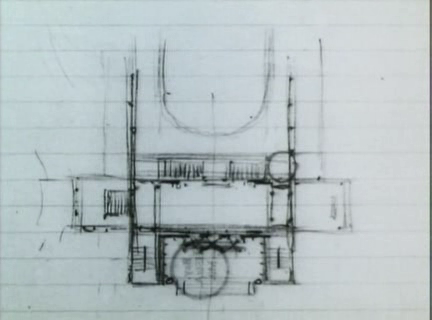

In a dense two hours, Architecture of Doom details the Nazis’ artistic obsessions. It includes Hitler’s favorite paintings, his architectural sketches and some of the Nazis’ most disturbing film reels.

In the early days of the regime, the Nazis attempted to eliminate what they considered degenerate art. That is, modern art that didn’t fit the party’s idea of perfection.

But it wasn’t enough to destroy the paintings.

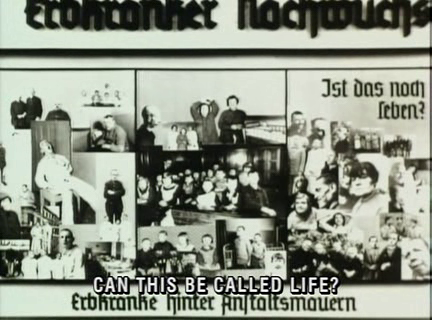

No, the Nazis took their degenerate art on tour. They wanted to prove that it was perverse. To that end, Paul Schultze-Naumburg—an architect and scholar—traveled Germany, lecturing on mental illness and modern art, flashing slides of avant-garde paintings beside pictures of disabled people.

It wasn’t long after Schultze-Naumburg’s lecture tour that the Nazis began rounding up the handicapped.

The T4 program—the Nazi’s early eugenics operation—was an extension of Hitler’s aesthetic ideal. It eliminated Jews, Gypsies and others the Reich considered undesirable.

It might be hard to understand now, but Hitler’s idea of who looked pleasing motivated his racial policies. Cohen’s documentary does a good job explaining that.

“Defining Nazism in traditional political terms is difficult,” Cohen concludes.

“Mainly because its dynamic was fueled by something quite different from what we usually call politics. This driving force was … aesthetic. Its ambition was to beautify the world through violence.”

“It was not enemies who were liquidated, nor opponents of the regime, but innocent people whose very existence was in conflict with the Nazi dream.”

Architecture of Doom explores that terrible, terrible, beautiful dream.