The Next Big Idea for the Next Decade — Aspen Ideas — Medium

The Next Big Idea for the Next Decade

Realizing the resilience dividend

Ten years ago, who would have predicted the rise of the sharing economy, the omnipresence of social media, or that selfies would take the world by storm? And given the rapid pace of change our world continues to experience, it is almost impossible to predict what our world will look like in 2024.

But that was our mission of sorts at this year’s Aspen Ideas Festival, which was celebrating its ten years of thought-provoking, and world-changing, discussions.

In a conversation with the Washington Post’s Phillip Kennicott, I made the case for why building resilience is among the most important priorities of our lifetime, provoked by the three trends I believe will most shape the world for the next decade:

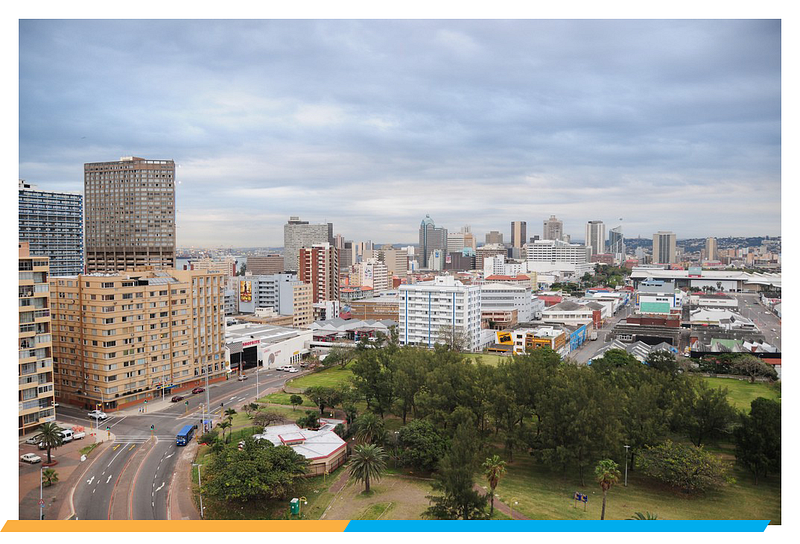

The first is the rapid, astonishing pace of urbanization. With a global population headed towards 9 billion by mid-century, people will be mostly located in cities, in increasingly fragile ecosystems.

The second is climate change, which, over the past decade, has emerged as an undeniable threat to cities, institutions, and businesses. For example, hot weather kills more Americans than all other natural disasters combined, and experts predict that summer heat waves will only worsen, leading to even more illnesses and deaths.

The third trend is globalization. Vulnerability in one place leads to vulnerability in another. Economic shocks and infectious diseases travel quickly, without mind for man-made borders. This will only continue to intensify.

These three factors form a crucial social-ecological-economic nexus, one that has huge—and, frankly, frightening—implications, especially for cities. The shocks and disruptions we experience today, like floods, wildfires, acts of terror, and pandemics, will only get more frequent, more intense, and more dangerous for more people. At the same time, cities also must confront chronic stresses, like crime, which develop more slowly than shocks but are equally devastating over time.

We can’t continue to delude ourselves that things will get back to “normal” someday. They won’t. It’s a losing game to continue to devote our resources to recovering from disasters that, by now, we should know to expect.

The good news is that today we have the tools, the networks, and the know-how to become more resilient. We at The Rockefeller Foundation define resilience as the capacity of individuals, communities, organizations and systems to survive, adapt, and grow in the face of shocks and stresses, and even transform when conditions require it.

And it’s not just about keeping bad things out. Resilience ensures that a city —or other entity—can continue to operate at its highest function on its best and its worst days. It’s a lever for unlocking greater economic development and business investment, as well as improved social services and more broadly shared prosperity.

This is what I call “the resilience dividend.” It has two components:

- First, it’s the difference between how disruptive a shock or stress might be to a city that has made resilience investments, compared to the degree of disruption the same city would face if it hadn’t invested in building its resilience.

- Second, it’s the package of co-benefits that investing in resilience can yield to a city—job creation, economic opportunity, social cohesion, and equity, to name a few.

Let me offer an example from my book, The Resilience Dividend, to be released this November.

You may know that Medellin, Colombia was once the most dangerous city in Latin America. For decades it was trapped in a downward spiral of violence and poverty, amid daily tragedies of murder, corruption, drugs, absence of services, and economic disparity.

In the 1990s, the city began to test new ideas and investments to create more resilient communities. One such focus was on mobility and transportation, ensuring that its most vulnerable and impacted communities were better integrated into the fabric of this city, with real access to work and to a variety of services including community centers, public art, health care facilities, and schools. To do this, they developed the first urban “cable car,” or gondola lift, which connects to the city’s subway system. They also built an escalator system climbing the hill to isolated communities, cutting the walk time from the hillside to the economic center of the city from about thirty minutes to about six.

These systems also serve a crucial function as an evacuation route in times of disaster, such as a mudslide or an earthquake, but are also integrated the poorest and most isolated communities into the city center, which has helped to cut down on crime.

Medellin is just one of many cities around the world working to build resilience.

Indeed, last year, The Rockefeller Foundation launched our largest resilience effort yet—100 Resilient Cities, a $100 million initiative to help 100 cities around the world increase their resilience to shocks and stresses, leveraging public finance and the resources of the private sector.

Thirty-two cities have been named so far, with the next group to come later this year: The competition for the second round opens to cities on July 23rd. The cities receive four types of support:

First, support to hire and empower a city Chief Resilience Officer, or CRO, a central point of contact within each city to coordinate, oversee and prioritize resilience activities.

Second, cities receive support to develop a resilience strategy that analyzes and mitigates their vulnerabilities and build on their unique strengths.

Third, cities in this network have access to a platform of services leveraging resources significantly beyond our own to support solutions that integrate big data analytics, technology, resilience land use planning, infrastructure design, and new financing and insurance products.

And fourth, cities become members of the 100 Resilient Cities Network, a peer-to-peer network that shares new knowledge and resilience best practices and fosters new connections and partnerships.

We believe that by creating a market for resilience products and services in 100 cities, more civil society and governments, and more private sector companies, will be incentivized to push the limits of technology and innovation, which will benefit all cities.

For example, exciting resilience innovations have come out of the 3-D printing revolution. In New York Harbor, we are rebuilding after Sandy with a new system to create pilings to replace the aging and cracking ones that support the city’s docks and piers. They’re produced by a massive 3-D printer using “digital concrete,” a new material that is more resilient because it is more flexible, adaptive and strong—and far more cost-effective to build.

That’s just one example of the kind of resilience service helping cities get an economic leg up while better preparing for what’s next. A community that takes advantage of these innovations can deliver incredible benefits for all its citizens, including its poorest and most vulnerable members—not only in times of distress, but each and every day.

Whether the next shock hits today or in 2024, the resilience dividend can help cities to survive, and even thrive, despite the shocks that come their way. The next ten years will see more of what were thought to be only 100-year occurrences.