Why Bikes Make Smart People Say Dumb Things

Michael Leuchtenburg: Why smart people say dumb things about cyclists: https://t.co/dRYanX8p9r

Why Bikes Make Smart People Say Dumb Things

An NPR journalist’s fumbled tweet exposes a hole in the debate about urban cycling

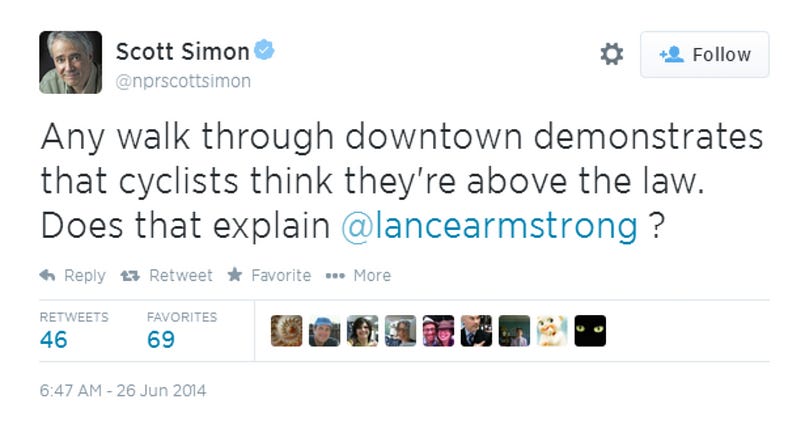

Simon also has one and a quarter million followers on Twitter, and last Thursday morning, he asked them this:

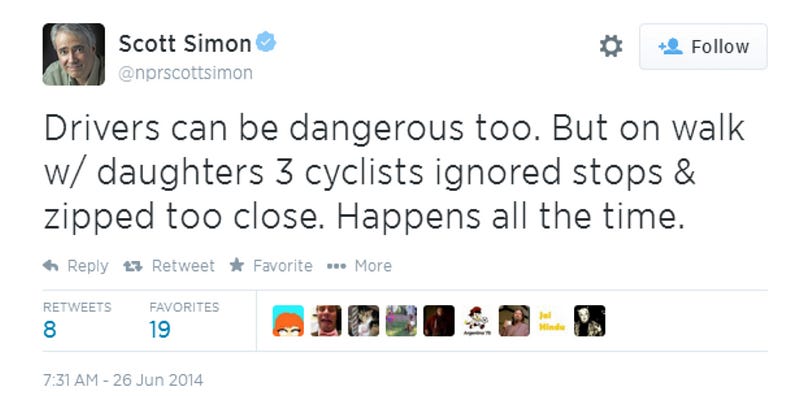

Now, you may have had this very thought, after watching someone on a bike blow through a red light, try and lane split through moving traffic, or do something similarly irresponsible. As Simon points out in a follow-up tweet, it happens all the time.

The problem, of course, is that no matter how egregious their behavior was, the three people he observed don’t indicate that “cyclists consider themselves above the law,” any more than a pair of jaywalkers prove that pedestrians are morally opposed to crosswalks. It also takes the very broad problem of traffic violations and limits it to a single minority, ignoring the millions of car and truck drivers who flout the law every day, not to mention those scofflaw pedestrians.

What Simon did in this pair of tweets was overgeneralize about a large group based on the behavior of a few members, and then tie that group to another member with a lot of bad press—two demonizing tactics that’ve been employed pretty much forever, to attack groups ranging from corporate lawyers to Asian drivers to welfare recipients.

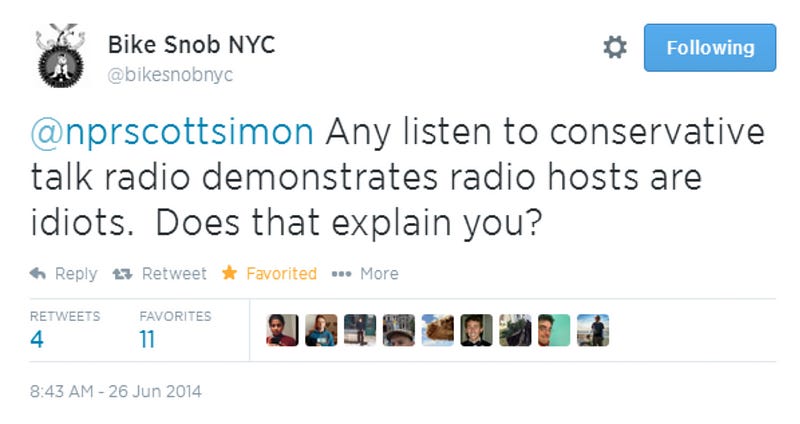

Numerous replies pointed out as much, the most entertaining coming from author Eben Weiss, who writes a popular long-running blog out of New York City called BikeSnob:

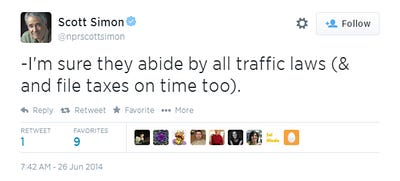

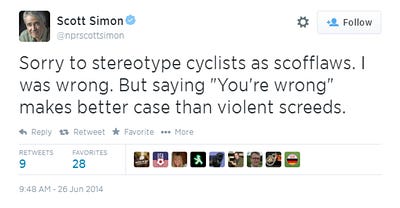

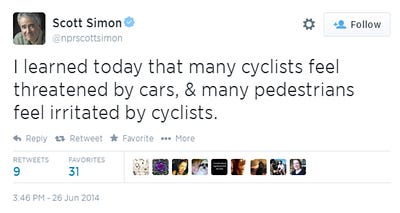

The rest of the exchange consisted of sympathetic followers favoriting and retweeting Simon’s posts, others responding in passionate agreement, and dozens more drawing attention to its obvious fallacy (in a generally civil tone—Weiss’ snarky retort was about as combative as it got). Simon followed up several more times over the course of the day, appearing at first defensive, then dismissive, and finally a bit chastened and almost conciliatory.

Now, there’s nothing unusual about this kind of bikers vs everyone drama, especially on the Internet: browse the comments section beneath a bike-related article on almost any broad-reaching publication, and you’ll find that few topics besides Israel, healthcare and gun control stir up as much debate.

What’s remarkable is that Simon should’ve known better. An experienced reporter with a sterling reputation for fairness, he’s one of the last people you’d expect to engage in this sort of stereotyping. And yet something made it OK for him to veer from fact into conjecture when talking about some people riding their bikes, in a way that would’ve been unimaginable in describing a professional, economic, ethnic or gender group.

After 15 million miles traveled, the Citibike program has still caused not a single fatality for either pedestrians or riders.

This exception is something I stumble across regularly though, in the media and in everyday life. Delia Ephron, the celebrated screenwriter of “You’ve Got Mail” and producer of “Sleepless in Seattle” was so perturbed by New York’s new Citibike bikeshare system last October that she wrote a 1000-word opinion piece for the New York Times, complaining that “these bicycles have made walking around the city much scarier.” It’s a bold statement, completely at odds with the evidence—as of last month, after 15 million miles traveled, the Citibike program has still caused not a single fatality for either pedestrians or riders, and fewer than 30 serious injuries, while helping to improve the overall safety of the city’s streets.

A similar bikeshare system has been proposed here in Portland, but was vocally opposed in 2011 by city commissioner Amanda Fritz, who cited the “unsafe behavior” of existing cyclists as a reason to avoid anything that might put more of them on the streets.

Even my mom has gotten in on the act, complaining several times of the menace that bicyclists pose to the citizens of Santa Barbara, where she lives. As evidence, she described once witnessing a pack of seven men on bikes, speeding down Alameda Padre Serra at 30mph in the dark, and being struck with terror, despite the fact that hundreds of cars travel that same stretch of road day and night at 35 or 40, posing a vastly greater threat.

In each of these cases, a thoughtful, intelligent observer is prodded by a mix of fear and anger to give an alarming anecdote more weight than an abundance of evidence, or even common sense. On a street carrying thousands of 3000 pound vehicles a day at 40mph or more, we focus our fears on the handful of 30 pound vehicles moving half that fast.

So what is it about people riding bikes that provokes so much fear and anger? I’ve posed this question to several friends and acquaintances over the years, and the answers I get mostly fall into three categories:

- they’re a threat to pedestrian safety

- they flout the law

- they interfere with an otherwise smooth-flowing system

There’s also the occasional fourth—that they’re freeloading on roads that drivers paid for—but this has been debunked so many times that that particular red herring is, thankfully, starting to die off.

Of the other three, the first two fall apart pretty rapidly in the face of statistics. The CDC reports that 59,925 pedestrians were killed by motor vehicles between 1999 and 2009, while bikes (which are used for about 1.6% of all trips in the US) killed 63 in that same period, or roughly 0.1% as many.

The likely conclusion is that people riding bikes don’t break more laws or fewer laws than when they drive cars, but they do break different laws.

The few studies that look at specific violations have found that people on bikes do roll through stop signs about 15% more than drivers do (at least in Oregon), but also that drivers roll through them almost 80% of the time, suggesting this is more of a human fault than a cyclist one. Meanwhile, a host of other infractions are almost exclusively the domain of motorists: speeding, dooring, aggressive driving, violating the three-foot passing law, etc.

There are a few areas where cyclists are more likely to break the law, most notably running red lights, though this is almost never a contributing factor in collisions (I suspect it’s because cyclists who run reds do so cautiously, since…well…they don’t want to die). The likely conclusion is that people riding bikes don’t break more laws or fewer laws than when they drive cars, but they do break different laws. Given that most cyclists are also drivers, it’s reasonable to think the levels of lawlessness would be consistent.

This leaves a third source of fear and anger, the belief that bicycles are adding confusion to what was a smoothly-running system. Of the three, this is the most grounded in fact: there are more bikes in American cities than in the past, riding on streets that were almost entirely optimized for cars, but have seen recent changes. Many streets in central Chicago, Portland or Washington DC today would look strange to a driver from the 1970s—with all the new striping, bike-specific signals and traffic-calming bumpouts, the urban environment is asking for different behavior from drivers. And some of the people biking on these redesigned streets act like jerks.

That’s what makes bikes so frightening: we prefer the devil we know, even when it’s infinitely more bloodthirsty than the one we don’t.

The problem with this belief, though, is that the smoothly-running system that bikes are disrupting already kills over 30,000 people per year. On the same day that Suchi Hui was struck by a cyclist in San Francisco, resulting in one of the only bike-on-ped deaths of 2012, around 82 Americans died in car crashes. Going by averages, roughly that many more died in car crashes the day before as well, and the day after, and every other day of the year.

We’ve been conditioned since infancy to ignore most of these fatalities, along with the behaviors that cause them. If you’re a typical American, your first experience of speeding was while strapped into a car seat, and you rode past half a dozen fatal accident scenes before speaking your first complete sentence. A lifetime of exposure has convinced us to normalize, dismiss or ignore most traffic violations, to the point where we routinely exceed the speed limit despite the knowledge that speeding causes more than 30% of all traffic fatalities.

This normalization is entirely a product of exposure, and that’s what makes bikes so comparatively frightening: we prefer the devil we know, even when it’s infinitely more bloodthirsty than the one we don’t.

Most Americans grow up bi- or tri-modal, getting around by car, on foot, and if they’re like Scott Simon, by transit, which makes these modes feel relatively safe. A driver who merges without signaling is like a pedestrian who crosses midblock is like a straphanger holding open the subway doors: annoying perhaps, but hey, we’ve all been there. It was probably because there wasn’t any real danger, we might tell ourselves, or maybe the intersection was badly designed. We can sympathize, and so we look for extenuating circumstances, unless the violation is particularly severe.

A 2002 study found that drivers are far more likely to see a cyclist’s infraction as stemming from ineptitude or recklessness than an identical one committed by another driver.

When a bike blows a stop sign, though, we’re more likely to see it as evidence that “cyclists think they’re above the law.” The social psychology term for this bias is “fundamental attribution error”: the tendency to attribute the actions of others to their inherent nature rather than their situation, and the less we sympathize with their situation, the greater the bias. A 2002 study from the UK’s Transport Research Laboratory found that it plays a starring role in our perceptions of traffic behavior, with drivers far more likely to see a cyclist’s infraction as stemming from ineptitude or recklessness than an identical one committed by another driver. It may also help explain why I’ve been approached more than once while holding my bike by random strangers, asking me to explain the behavior of another cyclist they once saw doing something stupid. I ride a bike, therefore I’m one of them.

It’d be more accurate to say that, like a lot of people in Portland, I’m quadra-modal, walking and riding my bike most days, driving and taking transit a few times a month. In New York, I used all four as well, though transit took the lead. Same for San Diego, but the car was on top. As a “member” of all four groups, I tend to see people as equally capable of doing something irresponsible regardless of mode, but statistics and experience tell me that the person in the motor vehicle is by far the most dangerous. I tense up when I see a cyclist approaching a stop sign without slowing all the way down, but I tense up a lot more when a car does the same. And I fantasize about a cop showing up and ticketing them both, so I can make it safely to work today.

My guess is that Scott Simon doesn’t ride a bike in urban traffic very often. Washington DC has a great subway system and terrible traffic, after all, and he might live too far from work for bike commuting to be feasible. This is completely reasonable, but it also illuminates a major obstacle to constructive conversation about active transportation in America: most of us still aren’t very multi-modal.

It would be tragic to derail this kind of enrichment because we can’t figure out how to have a real conversation.

That’s a pity, and kind of a Catch-22, because the best tool for overcoming all this fear and anger and bias is simply to get more people on bikes, and show them not only the joys and concerns of urban riding, but also its humanity and diversity. The main reason bike advocates get so excited about car-free riding events like Los Angeles’ CicLAvia or Portland’s Sunday Parkways is that they’re powerful bias-breaking tools, and do wonders to dispel the stereotypes that still permeate the discussion about cycling: cyclists are entitled hipsters, spandex-clad elitists, wild-eyed eco-warriors, scofflaw bums. These are harder to maintain when you’re surrounded by biking families of six, and retirees carrying dogs in their front baskets.

Getting rid of the fear and bias matters too, because it has real impact on the safety of individuals and the health and livability of cities. Harassment and aggressive driving are substantial threats to urban cyclists, and negative stereotyping gives drivers more justification to punish cyclists for obstructing “their” roads. Funding for bike and pedestrian safety projects can also hinge on the way decision-makers perceive cyclists; the Portland commissioner who opposed bikeshare, mentioned above, is just one example among dozens, of politicians and business owners leaning on stereotypes as they oppose active transportation spending.

This is a loss for all of us, whether we ride a bike today, we might ride one later, or we’ve pledged exclusive allegiance to our car. A city with a large population of regular cyclists is healthier, more efficient and more economically viable, and more importantly, it’s safer for all residents. It would be tragic to derail this kind of enrichment because we can’t figure out how to have a real conversation. Especially if the only thing standing in the way is a bike ride or two.