The cronjob that generates $4 million a year

The evolution of Buffer’s core scheduling

At the core of how Buffer schedules posts is one line of a cronjob configuration that hasn’t been touched since the very start when Joel founded Buffer. We still rely on that single cronjob that runs every minute of every day. While this configuration is the same, everything else around it has evolved. Today, Buffer schedules on average 300 posts per minute and over 432,000 posts a day. Here’s a look at some of the challenges and iterations we’ve made to the core of what we do—scheduling posts on social media.

Buffer—October 2010-June 2012

When Joel started Buffer in his bedroom in 2010 his goal was to validate that Buffer would be something people wanted to pay for. A way to schedule tweets in advance was his hypothesis, and he moved fast to get something working. Looking back at our codebase Joel’s 4th commit was to put up a pricing page. Commit #13 (a week later) is when he checked in the first instance of cron scheduling. That’s what I’d call—lean.

The first iteration of the scheduling worked like this:

- Cronjob executed every minute that gets status updates from the database that are due right now.

- The same cronjob process would post them one by one and mark as sent.

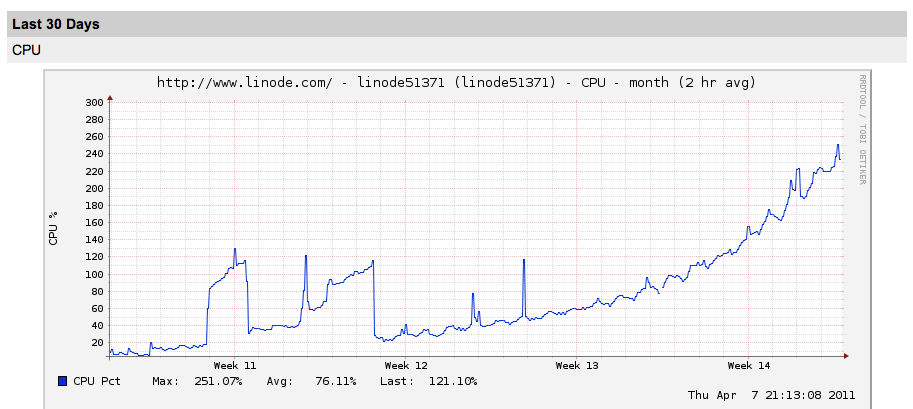

This was run in a single cronjob that ran on the Linode server that ran the web server and database. ($20/mo with 512 mb of RAM).

For a while this worked well enough. However, as customers started to schedule more posts, the cronjob would have to process more every minute. This slowly started to become more CPU intensive. When Joel would hit high CPU or memory usage, he vertically scaled the machines or optimzised SQL queries. Each time he upgraded the server, there would be a few hours of downtime but this was totally acceptable at that level of scale.

The switch to AWS—June 2012

In June 2012, with 100,000 users and some level of product-market fit in hand Joel and Tom decided it was time to migrate infrastructure so that scaling becomes a lot more, well scalable. They made the switch to AWS using elasticbeanstalk, SQS , and S3.

With this change, here’s how post scheduling looked.

- Cron job runs every minute on a single server and grabs updates that are due now.

- This cron job would then create an SQS (Amazon Queuing service) message.

- A worker running in a cluster of utility servers would pick off a message and process it. This worker would post the status update on Twitter, Facebook etc and mark as sent.

This new architecture formed the foundation for how Buffer works today. We’ve had an amazing experience using SQS and in almost two years of using it, haven’t had any unexpected message delay or downtime with it (knock-on-wood). It’s incredibly well architected and handles every thing we throw at it.

The separation of scheduling and processing was fundamental to tackling the challenges faced in scaling. Now it’s as simple as adding more workers to process the queue instead of upgrading to a server with beefier specs.

Concurrency

One of the early problems that was encountered when switching to this queue/worker set up was random unexpected behavior. Duplicate posting was probably the biggest and most noticeable one. Concurrency is often hard to debug, so there has been a lot of thought that went into understanding the flow and why issues like duplicate posting would occur.

To solve this, we designed a life cycle state machine of an update. We came up with these states throughout the course of an update being scheduled:

- buffer — currently in the buffer

- pending—picked off by the cronjob and added to SQS to be scheduled

- processing—picked off by a worker and currently being processed

- analytics/sent—finished sending and is viewable in analytics (analytics checking has its own state machine)

Even with this paradigm in place we still noticed that race conditions would occur, leading to duplication posts. This was a major issue for us and we worked hard to get this under control. To solve duplicate posting, we had to absolutely ensure atomicity when changing states. This is where MongoDB’s findAndModify comes in handy.

db.updates.findAndModify({

'_id':ObjectId(), 'status':'pending'},

{$set:{'status':'processing'}

});

FindAndModify allows one db connection to query for an update with a ‘pending’ status and atomically change the state so that another connection querying for the same update will see that it’s being processed. This general rule of ensuring state changes use findAndModify have helped resolve much of our concurrency issues.

Spiky Load

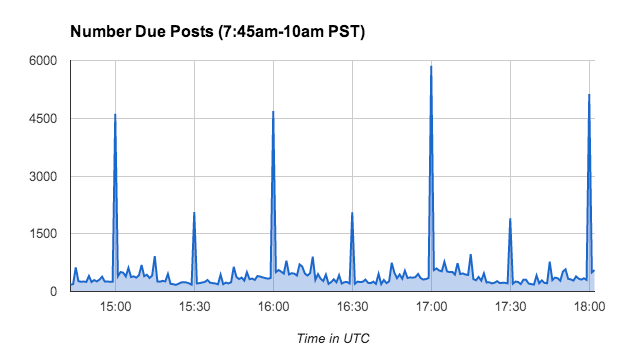

One of the really interesting challenges that we face at Buffer is the load from scheduling is incredibly spiky. Many Buffer users have set up their schedules to be hourly on the dot. This means that on a Thursday morning. at 7:59am PST there are 255 updates scheduled to be posted. As soon at 8:00 hits, we schedule close to 5000 updates to be posted. Then when 8:01 it’s back down to ~400 posts.

Here’s a visualization of when updates are due on Thursday (Feb 27) morning.

Posting Delay

As these spikes started to grow above 3k per minute, we started experiencing larger posting delays. When a customer would schedule a post exactly on the hour the post would have been seen on the social network a few minutes later than expected. The worst case we saw was an 8:00am post would be posted at 8:04. This was not acceptable.

After noticing these delays as a trend, we quickly realized that our poor cron job couldn’t handle the task of grabbing due updates and quickly adding them to our SQS queue to post during these spikes. Since the cron runs once a minute, the job would timeout as it could only process a few thousand a minute. Since the cronjob processing was part of the real-time scheduling path, it was at fault to introduce delay, especially for last thousand or so posts that were scheduled on the hour.

How we schedule posts today

In January 2014 we deployed a major change to our scheduling to ensure better real-time posting with minimal delays. To do this, we used SQS’s Delay Message feature. Effectively with SQS, we can schedule a message to be processed by our workers up to 15 minutes into the future. We made several changes so that our cronjob can start scheduling posts ahead of when they’re actually due. Now the scheduling cronjob will look for any post that is due in the next 15 minutes and adds it to the SQS queue with a delay so that our workers can process them at the exact time they’re due. It cuts out the cronjob as the middle man in the scheduling path and ensures we’re more real-time. As you might imagine, there were some major considerations and changes to handle if a post is added to our scheduling SQS queue and its due time gets changed (ie, if a customer changes the post’s due time).

This change has been a huge relief as we’re now able to horizontally scale processing posts by increasing the number of workers and our cronjob is no longer the limiting factor.

This post was super fun to write as it gave me a chance to reflect back on the challenges and evolution of how we schedule posts at Buffer. I’m still amazed that since the beginning and up to now this one line has powered our core product.

* * * * * php app/webroot/index.php cron tweet

Interested in working on some unique scaling challenges to manage sending out 3 million posts per week? Join our small team!