What tear gas taught me about Twitter and the NSA

Mark Forscher: Must-read. MT @agpublic: one of the best & clearest explications of the contemporary surveillance society. https://t.co/BgnrlBGpk7

Is The Internet Good or Bad? Yes.

It’s time to rethink our nightmares about surveillance.

Tear gas even taught me something about a subject I have studied for many years as an academic: social media. It was June 2013 and I was in the middle of the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul. After each volley of tear gas, protesters would pull out their phones and turn to social media to find out what was happening, or to report events themselves. Twitter had become the capillary structure of a movement without visible leaders, without institutional structure. Without even a name.

I was there to study the upheaval, this digital-era rebellion. But my mind kept wandering. Just a few days earlier, the first of Edward Snowden’s leaks had ricocheted around the world. We would soon learn a lot about the capabilities of the National Security Agency: that it can access data from the likes of Skype and Facebook; tap undersea cables and circumvent industry-agreed cryptography standards; hack into the connections that link giant data warehouses run by Google and Yahoo. And the agency, we would discover, used secret court orders to get the cooperation it required from industry giants—and to silence industry rebels.

This was not altogether a surprise; after all, the NSA’s mission includes the collection of “signals intelligence.” But the scale of the surveillance was shocking. And it was only possible because Internet and telecommunication companies have for years been amassing as much data as they can on their customers. Snowden didn’t just reveal specifics of what the NSA is doing—he also exposed an alliance of surveillance made up of governments and Internet corporations.

This alliance can monitor almost every click, and often does. (In fact, non-clicks are also scrutinized: Facebook tracks status updates that people start and then delete, so as to better understand why they decide not to post.) These clicks are increasingly linked to records of our offline lives. Commercial voter databases boast of knowing the IP, or Internet protocol, address of almost all U.S. voters. They can take data associated with this address and connect it with voting records, finances, purchases, criminal records, salary records, and other information.

Why do we give them our data? For the same reason that prompted the protesters to pull out their phones amid a swirl of tear gas: digital channels are one of the easiest ways we have to talk to one another, and sometimes the only way. There are few things more powerful and rewarding than communicating with another person. It’s not a coincidence that the harshest legal punishment short of the death penalty in modern states is solitary confinement. Humans are social animals; social interaction is at our core.

Yet the more we connect to each other online, the more our actions become visible to governments and corporations. It feels like a loss of independence. But as I stood in Gezi Park, I saw how digital communication had become a form of organization. I saw it enable dissent, discord, and protest.

Resistance and surveillance: The design of today’s digital tools makes the two inseparable. And how to think about this is a real challenge. It’s said that generals always fight the last war. If so, we’re like those generals. Our understanding of the dangers of surveillance is filtered by our thinking about previous threats to our freedoms. But today’s war is different. We’re in a new kind of environment, one that requires a new kind of understanding.

THE WORLD SHAKES WITH PROTEST AFTER PROTEST. Tahrir. Occupy. Syntagma Square in Athens, the 15-M movement in Spain. Now Ukraine. And these are just the spectacular street protests. Movements come in other forms, and not all of them are for causes that one may like: Anonymous, anti-vaccination, Slow Food, Tea Party. The ability to find like-minded people, to draw strength from them, to counter dominant narratives—these are things that make movements feasible. Just as happened in Gezi Park.

It began in late May, as a small protest against what seemed like an unstoppable juggernaut: the successful but polarizing Justice and Development Party (AKP) government. Gezi is a relatively little-known park, but it’s also the last bit of green in Istanbul’s Taksim Square, the heart of the city’s historic center for nightlife and art. Prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan imagined something else in its place: a replica of an Ottoman-era barracks—a barracks had once stood on the site—containing a shopping mall and upscale housing. For many, it was hard to imagine a worse scenario for this vibrant area than this mix of kitsch and rich. Erdogan’s plan met with protests from local residents, including artists, young professionals, and the city’s small but resilient LGBT community.

The protests resonated. The AKP is generally well-liked; the economy has prospered under its stewardship, at least until recently, and it has rolled out many popular policies, including the expansion of welfare programs. In the most recent general elections, held in 2011, it was reelected for a third term with a comfortable majority. Yet the AKP has also eroded checks and balances by placing supporters in all branches of government. And its urban renewal projects, while bringing money to the economy, have often involved replacing the delicate, historic vitality of Istanbul with gigantic shopping malls and cookie-cutter high-rise housing. Worse, the contracts to build them have often been awarded to those who curried favor with the government.

Very little of this has been discussed in mainstream Turkish media, partly because large conglomerates in Turkey have purchased television channels and newspapers, which they use to run sycophantic coverage of the government. The few big media outlets that dare run reports about corruption have been slapped with huge tax bills on the order of billions of dollars, which were then miraculously rescinded after coverage was blunted.

Yet Turkey is an increasingly wired country. You can hardly find a young person without a cell phone in Istanbul, and more and more of those are smart phones that connect to the Internet. So when a few dozen protesters tried to stop the bulldozers uprooting the trees in Gezi, and were pushed back with pepper spray, and had their tents burned, people learned about it from social media, not television. Twitter isn’t a traditional broadcast company; there’s no editor-in-chief who can be bought or pressured. So when the hundreds more protesters showed up, and were met with police, tear gas, and water cannons, people learned about it again on social media. Soon the protest was an order of magnitude larger. There were tens of thousands of protesters, in the center of the most central square in Turkey’s biggest city, fighting with the police.

It was still not on Turkish television.

The resistance, coordinated solely through social media and word of mouth, had gotten so large and tumultuous that CNN International began to cover it live. At the exact same moment, CNN Turkey was broadcasting a documentary about penguins. Someone put two televisions side-by-side, one tuned to the penguins, the other to CNN International’s live feed from Taksim, and took a photograph. It went viral, and penguins became the unlikely symbol of the uprising.

I WAS IN PHILADELPHIA WHEN the protests in Istanbul exploded, at a gathering called Data-Crunched Democracy, hosted by the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. It was supposed to be exciting, and a little contentious. But I’m also a scholar of social movements and new technologies. I’d visited Tahrir, the heart of the Egyptian uprising, and Zuccotti Square, the birthplace of the Occupy movement. And now new technology was helping to power protests in Istanbul, my hometown. The epicenter, Gezi Park, is just a few blocks from the hospital where I was born.

So there I was, at a conference I had been looking forward to for months, sitting in the back row, tweeting about tear gas in Istanbul.

A number of high-level staff from the data teams of the Obama and Romney campaigns were there, which meant that a lot of people who probably did not like me very much were in the room. A few months earlier, in an op-ed in the New York Times, I’d argued that richer data for the campaigns could mean poorer democracy for the rest of us. Political campaigns now know an awful lot about American voters, and they will use that to tailor the messages we see—to tell us the things we want to hear about their policies and politicians, while obscuring messages we may dislike.

Of course, these tactics are as old as politics. But the digital era has brought new ways of implementing them. Pointing this out had earned me little love from the campaigns. The former data director on the Obama campaign, writing later in the Times, caricatured and then dismissed my concerns. He claimed that people thought he was “sifting through their garbage for discarded pages from their diaries”—a notion he described as a “bunch of malarkey.” He’s right: Political campaigns don’t rummage through trashcans. They don’t have to. The information they want is online, and they most certainly sift through it.

What we do know about their use of “big data”—the common shorthand for the massive amounts of data now available on everyone—is worrisome. In 2012, again in the Times, reporter Charles Duhigg revealed that Target can often predict when a female customer is pregnant, often in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy, and sometimes even before she has told anyone. This is valuable information, because childbirth is a time of big change, including changes in consumption patterns. It’s an opportunity for brands to get a hook into you—a hook that may last decades, as over-worked parents tend to return to the same brands out of habit. Duhigg recounted how one outraged father, upset at the pregnancy- and baby-related coupons Target had mailed to his teenage daughter, visited his local store and demanded to see the manager. He got an apology, but later apologized himself: His daughter, it turned out, was pregnant. By analyzing changes in her shopping—which could be as subtle as changes in her choice in moisturizers, or the purchase of certain supplements—Target had learned that she was expecting before he did.

Personalized marketing is not new. But so much more can be done with the data now available to corporations and governments. In one recent study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers showed that mere knowledge of the things that a person has “liked” on Facebook can be used to build a highly accurate profile of the subject, including their “sexual orientation, ethnicity, religious and political views, personality traits, intelligence, happiness, use of addictive substances, parental separation, age, and gender.” In a separate study, another group of researchers were able to infer reasonably reliable scores on certain traits—psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism—from Facebook status updates. A third team showed that social media data, when analyzed the right way, contains evidence of the onset of depression.

Remember, these researchers did not ask the people they profiled a single question. It was all done by modeling. All they had to do was parse the crumbs of data that we drop during our online activities. And the studies that get published are likely the tip of the iceberg: The data is almost always proprietary, and the companies that hold it do not generally tell us what they do with it.

When the time for my panel arrived, I highlighted a recent study in Nature on voting behavior. By altering a message designed to encourage people to vote so that it came with affirmation from a person’s social network, rather than being impersonal, the researchers had shown that they could persuade more people to participate in an election. Combine such nudges with psychological profiles, drawn from our online data, and a political campaign could achieve a level of manipulation that exceeds that possible via blunt television adverts.

How might they do it in practice? Consider that some people are prone to voting conservative when confronted with fearful scenarios. If your psychological profile puts you in that group, a campaign could send you a message that ignites your fears in just the right way. And for your neighbor who gets mad at scaremongering? To her, they’ll present a commitment to a minor policy that the campaign knows she’s interested in—and make it sound like it’s a major commitment. It’s all individualized. It’s all opaque. You don’t see what she sees, and she doesn’t see what you see.

Given the small margins by which elections get decided—a fact well understood by the political operatives who filled the room—I argued that it was possible that minor adjustments to Facebook or Google’s algorithms could tilt an election.

I’m not sure if the operatives were as excited

by this possibility as I was afraid of it.

During a break, I cornered the chief scientist on Obama’s data analytics team, who in a previous job ran data analytics for supermarkets. I asked him if what he does now—marketing politicians the way grocery stores market products on their shelves—ever worried him. It’s not about Obama or Romney, I said. This technology won’t always be used by your team. In the long run, the advantage will go to the highest bidder, the richer campaign.

He shrugged, and retreated to the most common cliché used to deflect the impact of technology: “It’s just a tool,” he said. “You can use it for good; you can use it for bad.” (The scientist says he does not recall the conversation.)

“It’s just a tool.” I had heard this many times before. It contains a modicum of truth, but buries technology’s impacts on our lives, which are never neutral. Often, I asked the person who said it if they thought nuclear weapons were “just a tool.” Humans have always fought, but few would say it doesn’t matter if we fight with sticks, knives, guns, or nuclear weapons.

This time, I sighed and let it go. I wanted to get back to Twitter. I wanted to get back to my hometown.

I ARRIVED IN ISTANBUL A FEW DAYS LATER. I went down to Gezi, and soon heard local residents describe how they challenged Erdogan’s plans for the park through legal means. They faced a bureaucratic labyrinth Kafka would have been proud to have imagined. Requests to see the plans would disappear from government records. Officials who appeared too friendly to the requests would be reassigned. The residents filed petitions—and watched them disappear. They couldn’t even find out what exactly was being built, even though the land was publicly owned and subject to historic preservation laws.

Many told me that the reality gap between television and Twitter had brought them to Gezi. “I knew there was censorship on TV,” one told me. “But it wasn’t until Twitter came along I realized how bad it was. It’s one thing to be insulted discreetly, and another to be insulted so brazenly. I had to come here.”

I asked them what they were thinking of doing now they were in the park. Many didn’t know. At first, they just wanted to show up. They needed to see, to close the cognitive dissonance between their social media stream and their television.

Person after person told me how thankful they were for the Internet. Parents swore that they were going to apologize to their children, whom they had derided for spending too much time in front of screens. “They were right and we were wrong,” one woman told me. “We didn’t understand our kids. None of this would be possible without the Internet. The Internet brings freedom.”

IT WAS A STRIKINGLY DIFFERENT NARRATIVE to the one coursing through the country I had just left. As revelations about the scale of NSA surveillance flowed, sales of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell’s dystopian novel, shot up 6,000 percent on Amazon. Many came to see Oceania, the novel’s massive, fearsome surveillance state, as the model of the modern digitally-empowered state. Nineteen Eighty-Four had finally arrived, it was said—just off by 30 years or so.

But this is the wrong way to understand what’s happening. Deep and pervasive surveillance is real. It is likely worse than what we know, and is becoming more pervasive by the day. But Nineteen Eighty-Four has very little to do with it.

Others turned to a different metaphor: the Panopticon, a thought experiment invented by the 18th-century social reformer Jeremy Bentham and later popularized by the French philosopher Michel Foucault. Bentham imagined a prison with a tall tower at its center, located so that guards in the tower can peer into each prisoner’s cell. The gaze of the guards—all-seeing, but invisible to inmates—would make prisoners internalize the discipline of the prison, Bentham thought. Foucault later extended the idea by adopting it as a metaphor for the impact of surveillance on society.

But that’s also wrong. The Panopticon has little to do with most surveillance in liberal democracies.

And these metaphors aren’t just wrong—they can be profoundly misleading.

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the anti-hero, Winston Smith, lives under bleak conditions. Everything is gray. He eats stale dark bread. Informers and the cameras are everywhere. Sex is banned. Children spy on their parents. If a citizen defies Oceania’s harsh rules, a cage of rats is placed around his face.

This imagined future is an allegory for a fear-driven state, one inspired by Orwell’s views on Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Nineteen Eighty-Four is about surveillance in a society where the power of the state bears down on everyone, every day. In other words, it is about totalitarianism.

The Panopticon is a thought experiment: a model prison meant to control a society of prisoners. But we are not prisoners. We are not shackled in cells, with no rights and no say in governance.

In our world, pleasure is not banned; it is encouraged and celebrated, albeit subsumed under the banner of consumption. Most of us do not live in fear of the state as we go about our daily lives. (There are notable exceptions: for example, poor communities of color and immigrants who suffer under “stop-and-frisk” and “show your papers” laws.)

To make sense of the surveillance states that we live in, we need to do better than allegories and thought experiments, especially those that derive from a very different system of control. We need to consider how the power of surveillance is being imagined and used, right now, by governments and corporations.

We need to update our nightmares.

GEZI PARK WAS A PLACE OF BOTH resistance and celebration. It had the bursting vibrancy of a wildcat strike and the deep human solidarity that springs up after disasters.

One afternoon, as I chatted with a group of young people, an old lady dressed in traditional Islamic garb approached us. She burst into tears. “They are gassing young people. I can’t stand the idea,” she sobbed. A young woman dressed in shorts and sneakers, and sporting a nose-ring and tattoos, jumped up to comfort her. Soon after, a middle-aged woman offered me some börek, a Turkish pastry. “I don’t know much about how to protest, but these kids do,” she said. “But I know how to bake.”

A little later, as night began to fall, I interviewed a group of young people who had hung up signs condemning media censorship. The messages had been translated into two dozen languages. The arrival of darkness increased the likelihood of police intervention, prompting one young woman to take out a marker and write her blood type on her arm. “Are you this determined?” I asked. “We are a rainbow here and [Erdogan] is trying to paint us all black,” she replied. “We are a rainbow. We are not giving up.”

Gezi Park was indeed like a rainbow. I missed the whirling dervish in a flowing pink skirt (and gas mask), but caught the drum circles (with gas masks and helmets). Soccer fans came in large numbers. So did gays and lesbians, and they were more respected than I’d previously seen in Turkey. The LGBT community even got the boisterous, macho soccer fans to stop using “fag” as an insult—as is the standard in soccer slogans in Turkey—and chant “sexist Erdogan” instead. Devout Muslims distributed food to celebrate the Prophet’s birth; feminists handed out stickers reading “My body, my decisions.” I even saw a Kurdish group line-dance around a bonfire, watched by a man draped in the Turkish flag who sometimes tapped his foot with the rhythm—a scene I could not have imagined before arriving in Gezi, given Turkey’s tense ethnic relations.

They were united in resistance to what they saw as growing AKP authoritarianism, and deliberate in fostering an aura of pluralism. The unity held most of the time. That’s what can happen when people realize they are not alone. That’s what a street protest does, in its essence: It makes you feel not alone. We should leave aside the stale arguments about protests that happen on the street versus those that take place online. There’s one key feature that the Internet and the street share: They make us visible to each other. That is their power.

In fact, the Internet’s ability to break down “pluralistic ignorance”—the erroneous notion that your beliefs place you in a minority, when in fact most people feel similarly—is perhaps its greatest contribution to social movements. Facebook “likes” are often ridiculed as meaningless, but they can make a person realize that their social network feels the same as they do—and that’s a socially and politically powerful thing.

ONE LEARNS TO BE TEAR-GASSED. You tell yourself to keep calm as you head towards fresh air. It helps to remember that the gas probably won’t kill you. Of course, the canister itself could hit your head or a crucial internal organ, and that could kill you. But I was wearing a bike helmet. Most of the demonstrators around me were wearing yellow construction hats, sold to them by Turkey’s mostly Roma street peddlers. (From day one, the peddlers also offered spray paint, goggles, and other protesting essentials. Does anyone else in the world have better just-in-time stock management than dirt-poor street peddlers?)

The only thing in short supply was a proper gas mask; they had immediately sold out in Istanbul, and the peddlers only had flimsy “surgical” masks of the kind that doctors wear on television shows. Those are of no use against tear gas.

People who breathed in too much of the gas would vomit or fall to the ground, doubled up in pain. Protesters from the medical contingent would rush in, armed with makeshift stretchers, some made from old doors. Most of the wounded recovered. Some were sent to hospital. A few—those hit in the head by the gas canisters, especially—died.

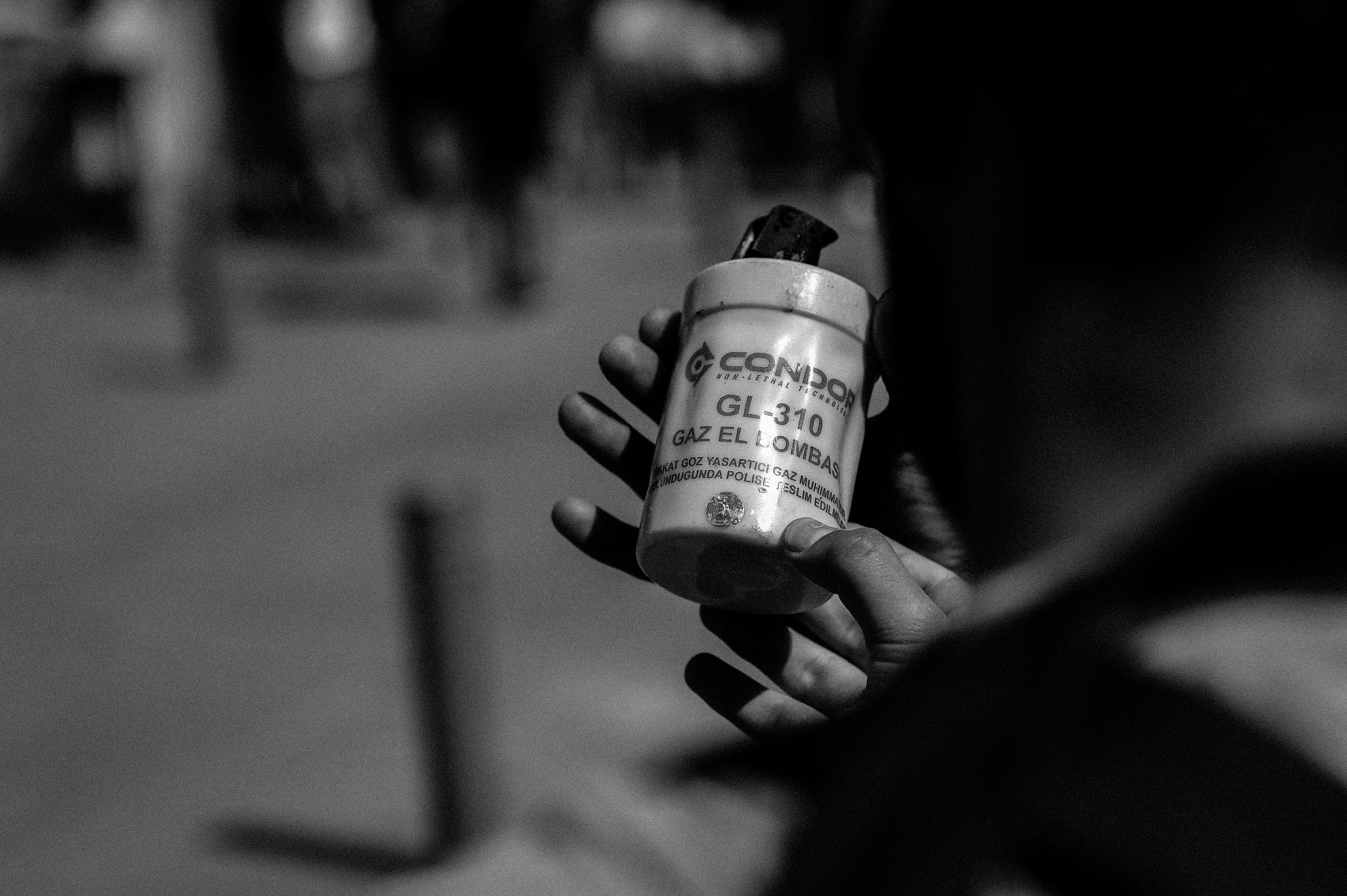

The protesters became tear gas connoisseurs: They could take one look at a canister and tell you what it was, what it did, and who made it. “This one, it’s the worst, it always makes you vomit,” a protester told me as he pointed to one canister among the dozen he had lined up outside his tent. There were constant discussions about remedies. Vinegar and lemon, commonly believed to be effective against tear gas, were disregarded in favor of a mixture of antacids and water. I believed them, because this was an educated, well-organized group that included chemists and doctors. (One example that was related to me: When the ammunition from another crowd-control weapon—water cannons—began to burn on contact, the protesters sent samples to a lab, which discovered that the government had added pepper spray to the water. Months later, a government spokesperson acknowledged this.)

After the horrific pain in our lungs, eyes, and throats subsided somewhat, we would pull out our phones and hit Twitter. This wasn’t vanity, or some desperate way to inform friends that we were okay—though letting people know we were alright was often a big part of it. In the middle of Gezi one had little to no idea of what was going on elsewhere, even at the other end of the park. Social media was a lifeline, and Twitter got the most use thanks the service’s phone-friendly simplicity and short message length. Crucially, Twitter relationships can also run one-way; I can follow you without you needing to follow me. As a result, users can interact with a large number of people, rather than just the smaller number of people willing to “friend” them.

Before I arrived in Gezi, I curated some tweets from the park and elsewhere in Turkey. Now I was spending my time listening and observing, and I found myself relatively clueless. I didn’t have the bird’s-eye view that comes from continuously following an event on Twitter. Friends from abroad would tweet questions—“What do you think of Prime Minister Erdogan’s latest statement?”—and I’d have no response. “I’m in the park, not on Twitter,” I’d reply.

So we got on Twitter when we could. Connectivity was generally good, perhaps because major phone companies stationed repeater vans in nearby streets. Twitter was a way to check whether the latest tear gas canister was a lone strike, or the start of an operation to clear the park. Were armored vehicles heading our way? Where was the governor? Was the political situation deteriorating or was there a move towards negotiations? The news, the conversations, the pictures, the recipes for neutralizing tear gas, the calls for donations, word of celebrities visiting Gezi Park—social media pulsed with these things. It was in the fabric of Gezi.

None of this means that there is less surveillance in Turkey than in the United States or Europe. In fact, there’s probably more. During its first years in power, the AKP replaced dusty ledgers with databases. Every citizen is now assigned a national ID number, which provides access to a government website documenting almost every interaction with the state, from property records to taxes. For many, it’s a relief to have escaped the country’s old bureaucratic systems. But the databases also enable massive surveillance. Citizens of Turkey need an ID number to buy a phone SIM card, for example, or to make a doctor’s appointment through the public health system.

Journalists, politicians, and pretty much all prominent people believe that the government goes further, and taps their phones as well. (Cartoonists often draw the state as a giant ear.) In fact, many protesters speculated that the government had not only allowed the Internet to stay up, but encouraged it. Those repeater vans may have been vacuuming up the ID numbers of the protesters. Somewhere in the government’s digital archives, there is likely a list of every Turkish citizen who visited the park during the protests.

Yet rebellion triumphed in Gezi, at least in the short term. The protests were eventually dispersed, but a court later ruled that the project violated rules about historic conservation. And the rebellion triumphed in another sense: People in Turkey started talking politics again, and social media became a highly charged and political sphere. The Gezi protests shook the image of AKP as unbeatable. Perhaps emboldened by the newfound spirit of challenge, other taboos unraveled. In December 2013, a corruption scandal, mixed with infighting among factions formerly allied with the government, rocked the country. Most of the news related to the scandal, once again, primarily circulated on social media as the government attempted to quash the investigation.

Not surprisingly, the government has been pushing back. Earlier this month, parliament passed an Internet censorship and surveillance law that makes it easy for government to shut down websites without judicial oversight. Internet providers are also compelled by the law to collect all traffic information on their users, and to turn it over to the authorities upon request.

AFTER THE ARAB SPRING I was asked the same question over and over again: Is the internet good or bad?

It’s both, I kept saying. At the same time. In complex, new configurations.

But the “bad” isn’t a watered-down version of Oceania or the Panopticon, at least not in modern democracies. In an era in which the ideas of citizenship and rights have taken deep roots, coercion based on violence is of limited use. Coercion alone can’t compel people to do the things modern states and corporations need us to do to keep the system going: to vote for their parties, to consume their products, to work in their corporations.

To understand the actual—and truly disturbing—power of surveillance, it’s better to turn to a thinker who knows about real prisons: the Italian writer, politician, and philosopher Antonio Gramsci, who was jailed by Mussolini and did most of his work while locked up. Gramsci understood that the most powerful means of control available to a modern capitalist state is not coercion or imprisonment, but the ability to shape the world of ideas. The essence of some of Gramsci’s arguments can be seen in another great dystopian novel of the 20th century. In Brave New World, Aldous Huxley envisions a state that eschews existential terror in favor of a drug, soma, that keeps its citizens happy and pliant.

Shaping ideas is, of course, easier said than done. Bombarding people with ads only works to a degree. No one likes being told what to think. We grow resistant to methods of persuasion that we see through—just think of ads of yesteryear, and of how corny they feel. They worked in their day, but we’re alert to them now. Besides, blanket coverage isn’t easy to achieve in today’s fragmented media landscape. How many channels can one company advertise on? And we now fast-forward through television commercials, anyway. Even if it were possible to catch us through mass media, messages that work for one person often fail to convince others.

Big-data surveillance is dangerous exactly because it provides solutions to these problems. Individually tailored, subtle messages are less likely to produce a cynical reaction. Especially so if the data collection that makes these messages possible is unseen. That’s why it’s not only the NSA that goes to great lengths to keep its surveillance hidden. Most Internet firms also try to monitor us surreptitiously. Their user agreements, which we all must “sign” before using their services, are full of small-font legalese. We roll our eyes and hand over our rights with a click. Likewise, political campaigns do not let citizens know what data they have on them, nor how they use that data. Commercial databases sometimes allow you to access your own records. But they make it difficult, and since you don’t have much right to control what they do with your data, it’s often pointless.

This is why the state-of-the-art method for shaping ideas is not to coerce overtly but to seduce covertly, from a foundation of knowledge. These methods don’t produce a crude ad—they create an environment that nudges you imperceptibly. Last year, an article in Adweek noted that women feel less attractive on Mondays, and that this might be the best time to advertise make-up to them. “Women also listed feeling lonely, fat and depressed as sources of beauty vulnerability,” the article added. So why stop with Mondays? Big data analytics can identify exactly which women feel lonely or fat or depressed. Why not focus on them? And why stop at using known “beauty vulnerabilities”? It’s only a short jump from identifying vulnerabilities to figuring out how to create them. The actual selling of the make-up may be the tip of the iceberg.

Companies want to use this power to make us buy products. For political parties, the aim is to attract support based on a tailored presentation of that party’s politicians and policies. Both want us to click, willingly, on a choice that has been engineered for us. Diplomats call this soft power. It may be soft but it’s not weak. It doesn’t generate resistance, as totalitarianism does, so it’s actually stronger.

Internet technology lets us peel away layers of divisions and distractions and interact with one another, human to human. At the same time, the powerful are looking at those very interactions, and using them to figure out how to make us more compliant. That’s why surveillance, in the service of seduction, may turn out to be more powerful and scary than the nightmares of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Yet here we are, still talking to each other. And they are listening.

//.

MATTER: The best writing, the biggest ideas.

Want more? Click the green button below to follow us on Medium. You can also sign up for our weekly pick of the finest long-form, find us on Facebook or connect via Twitter.

This story was written by Zeynep Tufekci, edited by Jim Giles and Bobbie Johnson, fact-checked by Cameron Bird, and copy-edited by Tim Heffernan. Jack Stewart narrated the audio version, and photographs were taken by Mstyslav Chernov, in conjuction with UnFrame.