Poisoned: why West Virginia’s water crisis is everyone’s problem

On his lunch break Friday — with his wife and child at home — he made a 45-minute drive to a mall in Huntington, which had not been affected by the water crisis. Eldridge started there, hoping to find bottled water and disposable 5-gallon water jugs at whichever store had any left to sell.

He visited Walmart, a Foodland grocery store, then a Target — all sold out in what Eldridge called “a trail of failure.” Then, at a sporting goods store, a clerk asked if he had a bucket with him to fill it up with water from an untainted Huntington tap. He didn’t, and after he and the clerk spent 20 minutes searching the store for one, they gave up. They were also sold out.

Eldridge drove back to work — easily an hour late returning from his lunch break — empty-handed.

‘Under the radar’

Freedom Industries — which was actually a conglomerate of smaller companies owned and operated by at least one convicted felon — had managed to escape the oversight of not only West Virginia’s DEP, but also the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). The reason? Various juries are still out. But consensus has grown around the idea that Freedom Industries’ chemicals were not considered “a hazardous material,” a DEP cabinet secretary told the Associated Press, so “it flew under the radar.”

The main problem was that Freedom avoided having to prove that it had designed a backup plan if its chemicals breached the porous retaining wall surrounding its toxic containment units and seeped into the ground. Or, worse, seeped into the river. Lack of worry about chemicals flowing into the river, in retrospect, seems absurd. Freedom Industries’ containment facilities sit maybe 50 feet from the Elk River’s shoreline, up a steep hillside covered with mud and leafless trees and bushes. “The idea that there would not be concern about those chemicals seeping into the river is a big problem,” Paul Ziemkiewicz, director of the West Virginia Water Research Institute, told The Verge. “If you would’ve had proper secondary containment on the site, this wouldn’t have excited anyone’s interest at all.”

Freedom Industries was also able to avoid submitting detailed instructions about how to deal with its chemical if spilled. Industrial companies that use solvents, for example, are required to provide OSHA with Material Safety Data Sheets that thoroughly explain procedures for how to work safely with a chemical, and how to avoid injury in the event of an emergency. Freedom wasn’t required to provide OSHA with detailed data sheets. Again, the jury is still out regarding why. But one theory is that there would have been little reason to think Freedom would’ve needed to. Who’s going to drink a coal-processing chemical?

Ziemkiewicz said Freedom’s chemical, MCHM, is classified by the EPA as a “foaming agent.” It’s water soluble, and it’s a surfactant — meaning that it reduces surface tension between a liquid and a solid. In coal processing, MCHM is used to break usable material from impurities such as dirt so that the coal can burn hotter and cleaner. There would’ve been no indication prior to last week’s events to suggest that MCHM would ever be ingested — accidentally or otherwise — by human beings in large quantities.

But all that didn’t excuse Freedom for its negligence.

In public hearings that have occurred since the leak became news last week, DEP inspectors have described their early interactions with Freedom as surprising, to say the least. The Elk River water situation only came to their attention after residents reported the liquorice odor last Thursday morning. They visited Freedom’s site around 11AM that day and asked the manager on duty if he knew of any problems on site. According to the Charleston Gazette, he told the inspectors, “There weren’t any problems.” Then things got weird:

The DEP officials asked [one of Freedom’s on-site managers] to show them around the facility. When they went outside, an employee asked to speak to [another Freedom manager]. After that conversation … DEP officials [were told] there was a problem, and led them to tank 396. There, the DEP officials said, they found a 400-square-foot pool of chemical that had leaked from the tank into a block containment area. Pressure from the material leaking out of the tank created what DEP officials called an “up-swelling,” or an artesian well, like a fountain of chemical coming up from the pool. They saw a 4-foot-wide stream of chemicals heading for the containment area’s wall, and disappearing into the joint between the dike’s wall and floor. Initially, no one saw the chemical pouring into the Elk River.

So it’s no wonder that regulators had to scramble when they realized thousands of gallons of an “under the radar” chemical had flowed into the region’s main water source.

‘Your water is poisoned’

What kind of crisis is this exactly?

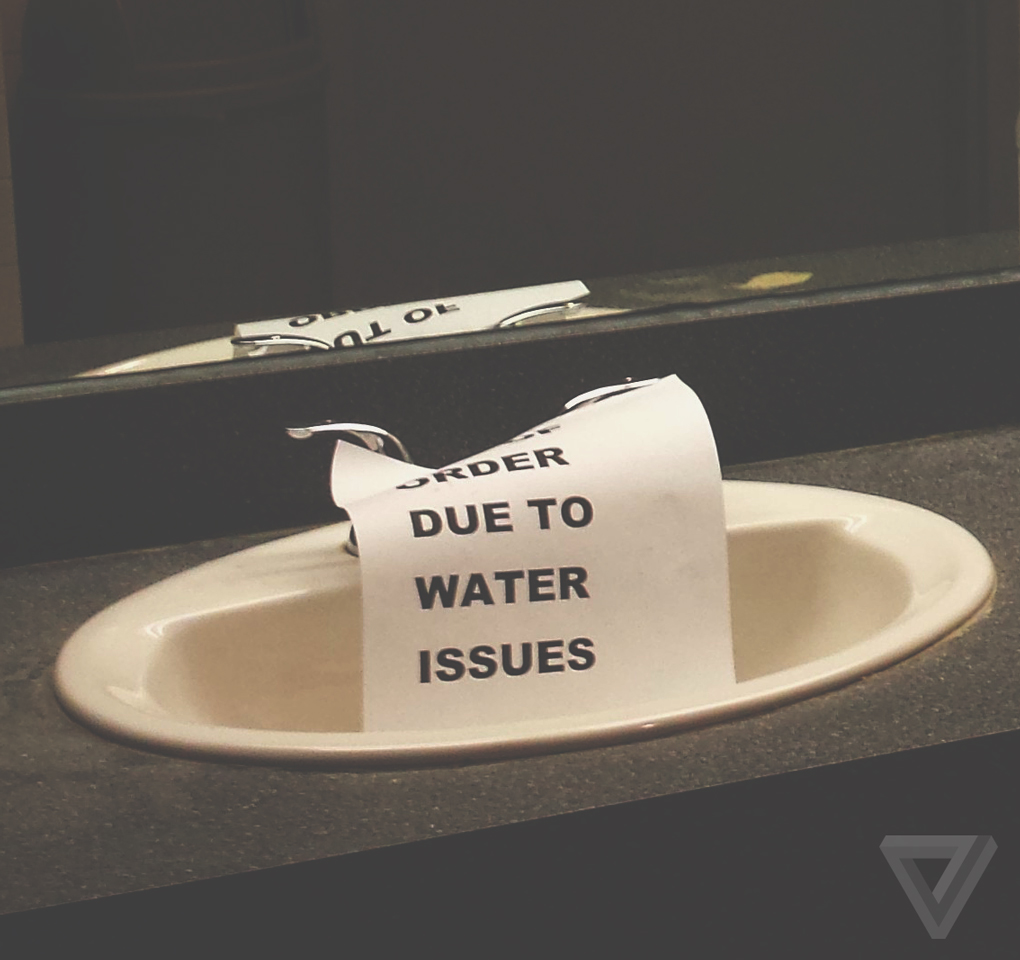

Well, first, it’s the kind of crisis where restaurants such as Steak Escape can operate while others remain crippled by a lack of water. The Steak Escape — featured on local news programs as one of very few restaurants that got permission from the Kanawha Charleston Health Department to operate on Sunday and yesterday — exists in a room attached to a gas station.

“As long as we’ve got a 5-gallon bucket [filled with clean water,] we’ve got enough water to run a business,” said John Kaiser, manager and co-owner of the franchise. And while other restaurants were suffering through the crisis (hundreds of similar shops were shut down on Thursday and many have yet to reopen), Kaiser said the water crisis was actually kind of a boon. “We’re the only shop on the block,” he said. “We’re going to do just fine through this. It’ll probably be our best week of the year.”

It’s that kind of crisis — a boon for a select few, an indescribable inconvenience for others.

“It’s weird,” Eldridge said, eating lunch yesterday at the Steak Escape, speaking loudly over conversations taking place in a long line of eager customers extending out the door. “I always think it’s fun when the power goes out. I like getting candles and just sitting down and reading a book. […] But this is really different. It’s not just that the water went out. It’s that the water was poisoned.”

By this point, during lunch yesterday, Eldridge had found water for his family. A friend of his father had been storing water in his basement and shared some. The Eldridge family had been able to bathe at a college friend’s house in Huntington. Shipments of bottled water had also made it to local stores, and local fire departments had received massive quantities of bottled water to give out, one case at a time, to anyone who needed it.

“What makes this weird is that there’s no way to know when it’ll end,” he said yesterday. “When a water main breaks and you lose your water, it’s such a priority to the town that the water is back up that day — often within hours. Sometimes sooner. But it’s really different when someone says, ‘Your water is poisoned. We don’t know when you can have it back. And you certainly can’t get near it, or do your laundry, or take a shower, or wash your dishes, or drink it.’”

‘It won’t come out and kill you’

As it turns out, the water began to turn back on just as Eldridge was eating lunch yesterday. Four full days after the crisis began, West Virginia’s governor announced that water could be flushed out of residential pipes — one geographic zone at a time — and people could begin using their water again.

Ziemkiewicz, the Water Research Institute director, said that the chemical Freedom Industries leaked into the Elk River was a nuisance. “It smells bad, it tastes bad.” But “it won’t come out and kill you.” Ziemkiewicz said a human would need to drink 1,000 gallons of MCHM at the concentrations seen in Charleston to be severely harmed. (Only a “handful” of people have been admitted to hospitals due to the water crisis.)

That’s not the real problem, however. The real problem is that this could’ve been much worse than it was.

Juliana Serafin is an assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Charleston. Born and raised in West Virginia, she got her PhD in physical chemistry from Harvard and then worked at companies such as Dow Chemical for two decades before joining the U. Charleston faculty to teach physical and organic chemistry. In her classes, she said, one of her assignments is a history lesson. She tells her students to research a specific chemical disaster and find out what went wrong. Just in West Virginia, she said, there are plenty of instances to choose from. There’s the Upper Big Branch mining explosion, for one, and a similar chemical explosion in 2008.

“There have been many close calls,” she said. “But usually we’re worried about the air. With this water crisis, this is one of the first times we’ve worried about our water. And we should be concerned. Because it turns out that 300,000 people get their drinking water from the same place.”

“A lot of it comes down to money,” she continued. “How much money do you want to spend on safety? How much effort do you want to put into regulating chemicals? Some companies will do the bare minimum and cut corners. But what are the repercussions?”

“This could have been really, really bad,” she said. “I hope we can go forward from this, to take measures that won’t let it happen again. Because it really can’t. Next time, it might end up much worse.”

Eldridge had similar worries.

“I just wonder how long we’ll remember how bad this was,” Eldridge said. “I mean, this is a clear sign that things need to change. But who knows if they will.”