How Antisec Died — Notes from a Strange World — Medium

How Antisec Died

Jeremy Hammond, Sabu, and the Intelligence-Industrial Complex

First, an introduction: I write about hackers, and for the past few years that has meant I write about Anonymous. At the time of the Stratfor hack I was working for Wired covering Anonymous — notably the antics of Antisec anons much of the time. I had missed the Lulzsec period, which I spent under federal investigation myself. From February to July of that year I stayed away from the hacker world, unsure if my computer would be seized and unwilling to draw my sources into a possible fishing expedition.

By the winter of 2011, I was making up for lost time. I’d become deeply

involved with the day to day lives of active anons working on all sorts

of actions, from Occupy support to street protests. And of course, I

talked with members of Antisec on a daily basis. In accordance with my rules for coverage, no communication with anyone in Anonymous was ever logged unless it was an on-the-record interview permitted for printing. Even then, my notes didn’t preserve handles, the format of communication, or even urls of places we’d communicated. I never knew who anyone was in real life, and made it publicly clear that I would never work with any anon who revealed their identity to me.

This was in part because I didn’t want my work to become involved in any court cases, but also because for the nature of my coverage, I didn’t believe, and still don’t, that the legal identity of individuals tells us much about the collective I was writing about.

As a result, much of the story I have to tell of what really happened to Antisec comes of years-old memories. There are almost no notes anywhere to support the conversations I will claim to have had with people I can no longer find and never knew in anything like real life. Some of the details may have faded from memory. But the story has not.

Jeremy Hammond, aka sup_g and crediblethreat,

was sentenced to 10 years last Friday in connection with the hack of Stratfor at the end of 2011. He was shopped to the feds by Sabu, the still unseen and unsentenced Lulzsec/Antisec hacker who spent nine months running the scariest hacker group ever on behalf of the FBI.

Depending on when one asked, Antisec was generally between 8-10 people, with a solid core of about six. Not all of them were comfortable with talking to me, and certain ones were designated to communicate with press. I was never entirely sure who was in or out at any particular time — it was a fluid group. I never knew all the nicks. I talked repeatedly with five of them, including Sabu.

He was extremely sexually aggressive with me, saying one of the first time we chatted, “I like you quinn, next time you’re in new york, you can watch me hack, naked.” I normally rolled with this from most anons, but he was so persistent, and kept telling me where he was. It disturbed me. He pressed me to meet him in real life twice while I was in New York. I refused both times, the second time, getting upset. No other anon had ever been so pushy and so transgressive of my coverage rules.

There was always something a bit off about Sabu’s voice. I assumed at

the beginning that “Sabu” was a collective identity — a not-uncommon

practice in Anonymous — run by several people of different backgrounds. I was corrected by several anons: Sabu, I was told, was one person, a hacker in New York.

It never seemed quite right to me. He wrote like multiple people. I accepted what the anons told me about Sabu, but I don’t think I ever believed it. I tended to avoid Sabu.

Sabu was never the leader of Antisec, there was no way a group that

unruly and anarchistic was going to take orders from anyone, even

someone as charismatic as Sabu. But for all intents and purposes, he did manage many of their engagements though a clever form of triage. Sabu sat in the #antisec channel on IRC with a topic saying that anyone who had found a vulnerability should contact him. Sabu didn’t get all the vulns, but he did get the vast majority, and thereby described most of the set of targets Antisec could even discuss going after. A few of the

members never cared that much who the targets were; they wanted to hack shit and had their own reasons for being part of Antisec.

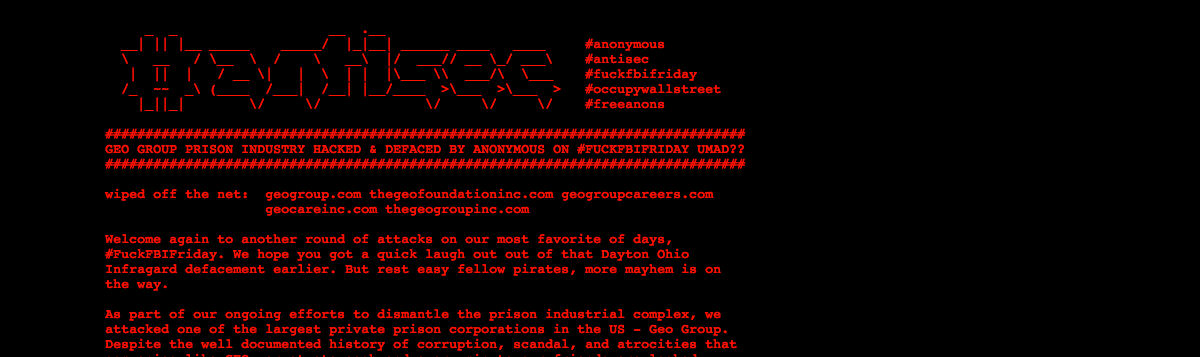

Not everything went through the whole group. There were a couple members focused on hacking prisons and prison companies, who, as far as I could tell, never consulted Sabu about it or cared what he might have thought. I don’t know why exactly, though there were implications, not just of experience of prisons, but of relatives that had or were serving time somewhere.

I never asked questions that could be identifying, but sometimes the

pain came down the line, sometimes in what was said, sometimes in the pauses.

Many of the Antisec members, like many of the other anons, had come by their anger though personal suffering. We could never talk about the details, but we didn’t have to.

The week before Christmas Antisec offered me an exclusive on Lulzsec,

their 2011 finale series of hacks.

I didn’t know it, but this would include Stratfor, a company I knew from their sketchy and unrealistic report about Anonymous going to war with Mexican Drug Cartels. Most of Anonymous knew who Stratfor was from this as well, and I suspect it was that report and the media that followed it which lead someone in the collective to find their vulnerability and turn it over to Antisec. On this point everyone I talked to was clear — the vuln had come from outside the group, and that person was out of touch not long after turning it over.

That the FBI supported the hack of Stratfor is without question. They called the company, as they had before, and told them to do nothing, as it would interfere with an investigation. They provided servers for the exfiltration of the data, as they had apparently provided servers in the past — one member told me after the revealing of Sabu that he’d regularly broken hashed passwords for the group.

No one had ever known where Sabu got that computing power, but they also hadn’t asked. It was nice to be able to turn over encryption to him and have it cracked and given back.

By January Antisec was so sure it was being monitored by the FBI that more than one member talked to me about it. A California police

association had gotten a warning that they were hacked from the FBI, and someone had told the media. Anons had noticed that — there was definitely a leak. The question, I posed, is which do you trust less, the network you use or the people you work with? They all suspected the people, but there wasn’t much more than suspicion, which Anonymous has in spades even on a good day.

Life went on.

In Feburary of 2012, Antisec had told me they had over 50

backdoored servers from governments and corporations, and planned to drop a new one every Friday for the indefinite future. These backdoors were shared in common; Sabu, and by extension the FBI, would have had them as well. Everything seemed settled into a smooth groove of hacking for 2012. The Stratfor mails were released by Wikileaks, but unlike most of Wikileaks’ sources, Antisec wanted credit. They came to me and gave me the most obvious story of my career — that they’d been the source of the Global Intelligence Files, a.k.a. the exfiltrated Stratfor emails. Wikileaks never confirmed, consistent with their policies.

On March 6th 2012, Sabu’s role working for the FBI was revealed, and

Hammond was arrested. The FBI had identified one of five or one of nine, depending on if you count all of Antisec or just those involved with Stratfor. The Bureau crowed their success on catching Hammond and subverting Monsegur for so long, nine months in total.

But why was this a success? It hardly seemed worth it for nabbing one guy. Antisec’s rampage had devastated corporations, embarrassed the government and poked holes in security all over the net. Most of Antisec was free, and even most of those who had worked Stratfor were never identified, and remain, to the best of my knowledge, free to this day. I talked with the remaining Antisec members, and many other anons, about how they felt after the revealing of Sabu, about what this had done to them and the collective. Between talking about how it all felt, the anons and I tried to work out what the FBI had really been after.

People revealed that Sabu had not only cracked passwords but solicited

shellcode for various systems as well as 0day vulnerabilities that could affect many systems. And, of course, there were all those backdoored servers all over the world.

The FBI may have only caught one hacker in the Antisec sting, but they walked away with a treasure trove of backdoors, vulnerabilities, and weaponized code.

I remember after one long conversation, there was a long pause on the line. It was all sinking in, how they’d been used and betrayed and broken. They’d all wanted to be activists, not criminals. They’d worked day and night without pay, using their rarefied skills trying to make a statement to power, and all the while, power had run them.

I told the Antisecs I was still in touch with, “I think the FBI owes you a few months of backpay.”

Three days after the FBI closed down their Antisec, the head of FBI Cybercrime, Shawn Henry, retired and went to the private sector to head up the Services division of Crowdstrike. Crowdstrike was the company most known for advocating “hackback” until that became unpopular (due to being illegal) at which point they claimed instead to be the most aggressive security company in the business at going after intruders. In the company’s marketing material Henry talked about determining attribution and understanding how the adversaries work.

He would certainly know a lot about hacking groups, after overseeing the most aggressive one in history for nine months.

On Friday Hammond released an amazing statement on what happened and what he believes in. It showed a powerful courage in the face of what was happening to him. He also started to list the countries where he’d hacked into servers at Sabu/FBI request, and was stopped by the judge who went on to redact the countries. An unredacted version was posted to pastebin. Its provenance is unknown to me, but surprising people have vouched for it in private. The document claims that:

These intrusions took place in January/February of 2012 and affected

over 2000 domains, including numerous foreign government websites in Brazil, Turkey, Syria, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Nigeria, Iran, Slovenia, Greece, Pakistan, and others. A few of the compromised websites that I recollect include the official website of the Governor of Puerto Rico, the Internal Affairs Division of the Military Police of Brazil, the Official Website of the Crown Prince of Kuwait, the Tax Department of Turkey, the Iranian Academic Center for Education and Cultural Research, the Polish Embassy in the UK, and the Ministry of Electricity of Iraq

I believe this list, personally, though I can’t prove it. I remember the

Brazil, Syria, and Colombia hacks, and some of the talk of Iraq and

Puerto Rico. Some of the docs were even screenshot and included in the Lulzxmas video. Some of the Brazilian defacements gave thanks to Antisec and Sabu in particular. Some documents from these hacks appeared online on the now-defunct Anonymous leaks site, par-anoia.net.

A couple anons told me they always felt like Jeremy (we didn’t use his

nicks anymore) was looking to get caught. I don’t know how much of this was comforting themselves, trying to make the whole thing, the betrayals and arrests after the evictions of the Occupy camps and the arrests of activists all over the world a little less horrible.

One posted that Jeremy was a political prisoner, that America had failed its ideals. Then he (he claimed to be a man) talked to absent Jeremy himself. As best as I can recall, he wrote “I remember about the Porsche,” mysteriously. And then: “I will not forget you, friend.”

Anonymous, as always, goes on. Antisec, as the group Sabu founded, disbanded and blew to the winds in 2012, but the concept remained. While hacks aren’t happening as often don’t grab headlines anymore, anons to this day take down sites and leak data flying the Antisec flag all over the world.

Nigel Parry also traced many of these events back in 2012, and spoke at a time I did not feel I could. While there are gaps in his coverage, he did a good job of lining up many of the facts.