The environmental scandal that’s happening right beneath your feet

Medium: “The environmental scandal that’s happening right beneath your feet” by @readmatter https://t.co/imym3xDvAl

The Environmental Scandal That’s Happening Right Beneath Your Feet

Uprising: Winner of the 2013 AAAS Kavli award for online science journalism.

BY THE TIME BOB ACKLEY crossed the Harlem River into Manhattan he’d been up for nearly four hours. It was still dark, not yet seven on a Sunday morning: the best time of the week to go sniffing for gas.

The back seat of his hatchback was littered with hi-tech equipment. Plastic hoses and cables connected a web of instruments: a laser spectrometer, a computer, GPS equipment, a pump, and a fan. The jumble of gadgets purred reassuringly as he drove.

Few people understand the streets of America’s cities the way Ackley does. He’s spent almost three decades documenting leaky gas pipelines and alerting utility companies to potential danger. Now he can read the street like a hunter reads animal tracks; some academics call him the “urban naturalist”.

As he drove through New York, Ackley looked for the signs that could point to possible gas leaks. Wearing a tattered winter jacket and peering out from beneath a baseball cap that proclaimed “Life is Simple, Eat, Sleep, Fish”, he searched for spray-painted signs that mark underground pipes and wires.

He watched the weather, knowing storms bring low-pressure systems that draw gas up from underground. Small holes drilled into the pavement; long narrow patches of asphalt; dead grass on the side of a street: these are all good indicators of past — and perhaps ongoing — leaks.

Even so, the Manhattan streetscape was hard to read that December morning. Concrete and asphalt ran from building to building without a blade of grass in between.

The only escape routes for gas were manhole covers.

“I’ve never had such a hard time pinpointing leaks,” Ackley said. “It’s as tight as a bull’s ass.”

Ackley, who is 53, has lived in working-class neighbourhoods around Boston all his life. He has a hard-bitten manner and speaks with the local nasal drawl. His politics are libertarian and his preference for president last year was Ron Paul, a Republican who pledged to disband the Environmental Protection Agency. His first car, bought at age 16, was a gas-guzzling Chevy Impala, and he has ridden the subway just twice in his life.

None of this makes Ackley the model of an environmental champion. But it’s not what he believes that makes him so important to the green movement: it’s what he knows.

Over the past few years, Ackley, a community-college dropout with no formal scientific training, has been amassing data that could answer a key question in energy policy. Since the early 1980s, western governments have been moving away from coal and embracing natural gas, a supposedly more environmentally friendly fuel. It’s a big bet, with huge consequences for global warming.

But as Ackley crisscrosses urban America, he is discovering that the country’s cities are peppered with gas leaks. So many, in fact, that some scientists now believe that natural gas may be accelerating climate change in a way that few had suspected.

Ackley still remembers the first time he found a gas leak. The son of a golf-course greenskeeper, he grew up in Northborough, a small suburban town close to Boston. It was 1979, and he had taken a summer job with a local company that mapped gas leaks for utilities. The country was reeling from the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island, Jimmy Carter was president, and My Sharona was playing on the radio as Ackley — then just 20 — sat in the passenger seat of a sky-blue Dodge Aspen.

His boss had the wheel. Roland Boucher was an older, heavy-set man with pale white skin and ruddy cheeks. A mess of electronics sat between the dashboard and front seat, with tubes connecting to a black box the size of a lunchbox. Just a few metres below them, encased in the soil, streets and yards of Massachusetts, natural gas mains and smaller service lines spread out like the bronchioles of a human lung. As his map flapped in the road-wind, Ackley focused on the instruments and tried to spot a leak.

Boucher told him to look up instead: “You look for dead trees, dead grass and dead shrubs.” It seemed too crude, but a moment later Boucher swerved to the curb. A Norway maple stood in a patch of dead grass by the side of the road. The tree was also dying, its top branches barren twigs. The air held the foul odour of rotten eggs —mercaptan, a chemical added to natural gas to make it easier to detect leaks. Boucher poked around the roots with a steel bar and pushed the snout of a gas meter into the earth around the tree. The needle jumped: well over 20 per cent of the air in the soil was natural gas. The figure should have been less than one per cent.

Methane was leaking from an underground pipe and seeping into the ground above.

They found half a dozen leaks that morning, and Ackley would find countless more in the years he spent driving across north-eastern America on contract for local gas companies. The pay was good, he enjoyed the travel, and the work was easy — days often ended in the nearest bar. He abandoned his education when Mandy, a pretty young brunette he’d been dating, announced she was pregnant. The couple wed in 1982, and Ackley used his college savings for a down-payment on a house not far from where he had grown up.

Over the years he grew from a lithe, shaggy-haired kid to a stout thirty-something with a receding hairline. Afternoons once spent at the bar were now occupied by Little League games and caring for his eldest daughter, who has a mental disability. It wasn’t quite what he’d envisioned for himself, but all things considered it was a good life: he and Mandy had three more kids, a home in the suburbs, holidays on Cape Cod each summer.

As time went on, however, something about his work bothered him. He couldn’t help noticing that gas from some leaks would continue seeping into the soil for years after he reported them. Some were what the safety guidelines called grade three leaks — minor problems that could safely be ignored. But many were grade two, meaning the leak was spreading closer to a home and needed fixing. One spring morning in the late 1990s, in the town of Winchester, Massachusetts, Ackley found a row of giant oak trees that were slowly dying from grade two leaks. He was pretty sure he’d reported the problem several years ago.

The next morning, Ackley knocked on the door of Joe Downing, an affable mid-level manager at the Boston Gas Company who oversaw the utility’s regional leak survey. Downing was tall and slender, almost gaunt. Ackley remembers that everything in his office, from his desk to the steel bookshelf, was coloured in shades of Boston Gas blue. A plaque commending him for decades of employment hung on the wall.

Downing smiled as he waved Ackley into the room. They got on well, often walking down the hallway, past photos of the 19th-century Irish gas workers who had laid the region’s cast-iron gas pipes, to the cafeteria, where they would curse the New York Yankees over coffee. But Ackley remembers the conversation turning frosty when he mentioned the Winchester leaks. Downing said they were grade three; Ackley replied that he’d listed them as grade two. He described the trees: withering, gnarled old oaks with trunks nearly a metre thick, standing in soil that was full of natural gas. “That’s not grade three,” Ackley said. Downing stood up, signalling that the meeting was at an end.

Around the same time, Boston Gas and other utilities began replacing the existing classification scheme with guidelines of their own. No laws were being broken, since the regulatory scheme was only a suggested method, and a weak and vague one at that. But under the new system, tree damage was no longer a factor: damage to vegetation could be noted, but it would not change the classification. (Downing died in 2002; Boston Gas declined to comment on its specific leak policy, but a spokesman noted that leaks that present potential public safety risks are addressed immediately.)

Friends and neighbours told Ackley that he should take action against the gas companies for the damage that leaks were doing to trees. But he was less sure. After all, whenever he found a leak that was genuinely dangerous, the utilities fixed it. And he had an easy job that paid well — the last thing he wanted was to make waves. “I knew it was wrong,” Ackley said recently, looking back, “but what was I gonna do?”

§

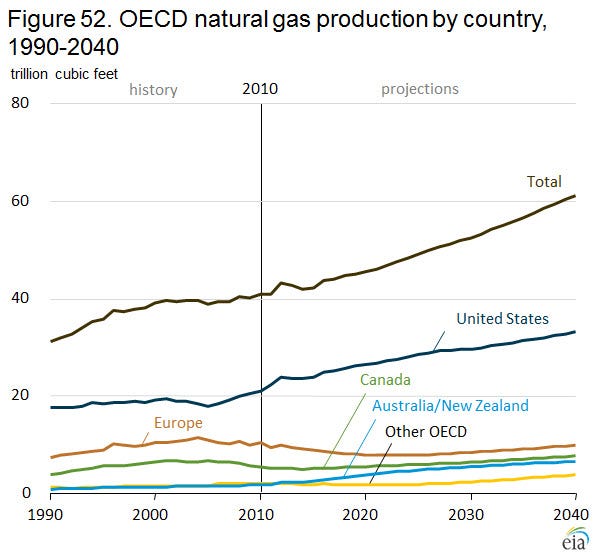

AS FOSSIL FUELS GO, NATURAL gas has a pretty good reputation. When burned, it emits roughly half as much carbon dioxide as coal, and it is cheap and plentiful, partly because new techniques — such as hydraulic fracturing, better known as “fracking” — have opened up access to vast new deposits. For environmentalists, low-carbon sources such as solar are still preferable, but, while we wait for those technologies to mature, gas is seen as a way to wean ourselves off coal.

Since the Reagan era, when the American Gas Association first began touting its product as a bridge fuel, this idea has established itself among many of the world’s leading energy experts. Among those who have championed gas is Ernest Moniz, a physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who was appointed as Barack Obama’s next energy secretary in 2013; Moniz has called gas “a bridge to a low-carbon future”.

This thinking has changed energy policies across the world. Many governments now see a switch from coal-fired power plants to gas as a way to reconcile energy demands and climate change. In his 2012 state of the union address, Barack Obama noted that America’s natural gas supplies can last a century and promised to take “every possible action” to safely exploit them. Using gas proved, he added, that “we don’t have to choose between our environment and our economy”.

Obama’s ambitions are symbolic of what the International Energy Agency calls the “golden age of natural gas”. China expects to triple its use of natural gas by 2035 to help meet its energy demands while simultaneously reducing pollution. The British government approved fracking in December 2012, calling it a stepping stone to a low-carbon economy. To these countries, natural gas is the least dirty of a dirty bunch; a palatable stopgap while we wait for a greener future to arrive.

But not everyone agrees.

In 2011, a landmark paper was published in the journal Climatic Change. The study concluded that burning natural gas — and in particular gas obtained through fracking — was worse for the climate than burning coal. The study drew a lot of attention, both positive and negative. Time magazine described the paper as one of the most controversial scientific studies of the year, and named its authors, Cornell University researchers Robert Howarth and Anthony Ingraffea, among the world’s most influential people.

The Cornell study focused on a poorly understood problem with methane, the main constituent of natural gas. Methane’s green credentials only apply when the gas is burned. If it escapes into the atmosphere instead, methane acts as a potent greenhouse gas — in fact, it is over 20 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide. The issue was well known but little studied: methane does not hang around in the atmosphere for long, so scientists had assumed that the odd leak would not undermine its use as a bridge fuel.

Howarth and Ingraffea punctured that assumption. As much as six per cent of the natural gas produced for our energy needs, they said, leaked into the atmosphere somewhere between extraction and use. The figure included gas that escaped from wells during extraction, losses at processing facilities and leaks from the systems used to transport and store the fuel. For gas obtained through fracking, the upper limit was even higher — almost eight per cent — due to increased emissions from the rock-fracturing technique.

These numbers were shockingly high, more than double the official estimates from the Environmental Protection Agency. And they changed the impact of natural gas on the climate. At six per cent, natural gas comes out the same as coal when considering emissions over a 100-year period, but worse over 20 years. At eight per cent, natural gas is worse than coal, regardless of the time period. Howarth and Ingraffea weren’t suggesting that consumers should revert to coal-fired hearths. But that big bet on gas? Suddenly it was being called into question.

The gulf between the official numbers and the Cornell estimates wasn’t a surprise to some. John Bosch oversaw emissions estimates for the EPA for more than 30 years before retiring in 2009. Emissions estimates were based on voluntary participation from industry, and only companies with good leak management programs volunteered. “My experience is that when regulators start looking at actual emissions the figure can easily double,” says Bosch. In fact, when real measurements are taken, the difference sometimes turns out to be even greater than that. In 1988, one oil refinery in Sweden recorded gas emissions that were 20 times higher than official estimates for the same facility. More recent data from natural gas processing plants in Canada put emissions at between four and eight times official levels.

In his time at the EPA, Bosch played a key role in developing and implementing the organisation’s emissions estimates for a wide range of industries, including gas. He now says that if he could do it all over again, he would never use those estimates. When the models were tested against real data, for instance, gas companies were sometimes allowed to recommend which of their facilities were tested, or to provide only a small data sample. “It made it too easy for industry to lowball the figures,” says Bosch.

“If they are too high, what the industry does is bitch like hell until they get more data and get them lowered.”

Among those now questioning the virtues of natural gas is Nathan Phillips, director of the Center for Energy and Environmental Studies at Boston University. The son of a Pennsylvania coal-mining family and a refugee from what is now North Korea, Phillips is 46, tall and athletic, with a smattering of white in his black hair. He began his career studying the physiology of trees, but in recent years has broadened his focus to the urban environment: chimneys, exhaust pipes, buildings, pipelines, pavements. He’s a leader in the emerging field of urban ecology and an expert on carbon footprints, the metric used to gauge the volume of greenhouse gases that a person or community emits during the course of their everyday activities.

Phillips obsesses about his work, and tries to reduce his own carbon footprint in every way he can. Every morning he cycles nearly 15km to his office, sometimes hauling unused food from his son’s school to a local food charity. When he arrives at his building on campus, he walks the four stories up to his office. Inside sits a bike connected to an electric generator; his slow and steady pedaling produces enough energy to light the room and power his laptop. Next to his desk is a handcrank generator, which he sometimes uses to charge his mobile phone.

Phillips read Howarth and Ingraffea’s paper, and was concerned by what the Cornell scientists had found. “If we do it right, I think natural gas can be a bridge fuel,” he says.

“But we’ve got to do it right. If you leak just a little bit of it along the way, it can have a tremendous impact.”

Like many other scientists, Phillips also noticed weaknesses in the Cornell paper. Critics of the study focused on its estimates of emissions at fracking wells, which were very high and based on limited data. But the data on gas leaks was extremely sparse, too. It was one of the shortcomings that had led the natural gas industry to attack the study as “activist research” that made “inaccurate and extreme choices far outside established science at virtually every turn”. The paper itself acknowledges plenty of uncertainty, not least because it pegs the lower limit for leaks at a shade below two per cent, which, if correct, would leave methane’s green reputation intact.

Phillips decided to investigate for himself.

When he looked at public data on leaks, what he found astounded him. The US government’s Energy Information Agency logs “lost and unaccounted for” gas, which it defines as the difference between the amount of gas that utilities buy from wholesalers and that which they sell to users. In Massachusetts alone, over 140 million cubic metres of gas was lost every year. Nationwide, the figure was over 8 billion cubic metres —equivalent to the greenhouse gas emissions from more than 30 coal plants. The American Gas Association, which represents gas utilities, claimed the primary cause of the losses was “meter uncertainty”. In other words, that the lost gas was actually just a blip in measurement. Phillips wanted to know more: that would have been some blip.

What puzzled Phillips, at first, was why the gas industry did nothing about it. In purely financial terms, the amount of gas lost nationwide had a value of more than three billion dollars. Why would they let so much money leak out of their pipes? The answer, he discovered, was that state regulators allowed the companies to pass on the cost of lost gas to ratepayers. Utilities had little incentive to fix small leaks.

Phillips knew that if he could figure out how much gas was actually leaking from the ageing pipes buried under a large US city, he could plug a major gap in Howarth and Ingraffea’s findings. Perhaps he could provide a definitive answer on the gas versus coal debate. Even if he couldn’t, better numbers might help pressure the gas companies into plugging the leaks. But to do it, he would need some help.

FOR NEARLY A DECADE, ACKLEY wrestled with the knowledge that the leaks he was recording were not always being fixed. And it wasn’t just the dead trees that bothered him. Natural gas pipeline explosions in the United States kill an average of 14 people every year, and injure an additional 50 or so. In 2010, an explosion in the Californian city of San Bruno killed eight people and destroyed almost 40 homes. An independent audit ordered by state regulators found that the local energy provider, PG&E, had spent 15 years diverting more than $100 million in funds earmarked for safety and operations into other areas, including executive bonuses.

The following year an explosion in Allentown, Pennsylvania killed five; regulators called the safety record of UGI Utilities, the company that owned the pipeline, “downright alarming” and fined the corporation $500,000.

Back in 2004, when Ackley was surveying for gas companies, an explosion in nearby Natick, Massachusetts, hit particularly close to home. Eighteen-year-old Eric Brack was with his father when a manhole cover weighing over 80 kilograms shot into the air and crashed through the front window of their car. The cast iron disk hit Brack in the chest and head, leaving him permanently disabled.

The local gas utility, NSTAR, described the incident as an extremely rare reaction to an electrical failure, and said that a build-up of methane in the manhole might have contributed to the explosion. Brack’s family settled out of court, so the exact cause of the blast was never made public. Ackley remembers mapping leaks on the street repeatedly in the 1980s and early 1990s. “Any leak has the potential to be hazardous,” he said recently. “But nobody cares until somebody gets hurt.” (NSTAR did not respond to a request for an interview about the incident).

Ackley had moved from company to company, but found a similar attitude towards leaks wherever he went. By 2006, his conscience was starting to get the better of him. His kids were grown up, Mandy was bringing in additional income as a gymnastics instructor and he’d made some good investments in stocks and real estate; he figured he had enough money stashed away to last him three to five years. So, while working in Connecticut one morning, he picked a fight with his boss and walked off the job. It brought an end to a nearly 30-year career as a gas company contractor.

Bob Ackley spent nearly 30 years working for the gas industry: now he’s switched sides.

His idea was to blow the whistle.

Over the next few months, Ackley prepared a presentation — including internal gas company documents and photos of trees suffocating from natural gas — and began cold-calling environmental law firms in Boston. He was turned away each time, so he tried contacting Jan Schlichtmann, a hotshot lawyer he had read about in a local newspaper. Schlichtmann was famous for winning $8 million from chemical company W.R. Grace & Co., which had contaminated wells in the nearby town of Woburn, giving children leukemia. The high-profile case had turned Schlictmann into a local celebrity and formed the basis for A Civil Action, a movie in which John Travolta played the lawyer.

Ackley called Schlichtmann’s office and managed to get a lunch date; the lawyer suggested Cygnet, an appallingly fancy restaurant just north of Boston. Ackley remembers feeling distinctly out of place among the upper-class clientele. Schlichtmann’s manner didn’t help. Tall and wiry, with a bushy moustache and grey hair, he looked like a professor but had the patience of a schoolboy. The lawyer grabbed Ackley’s laptop and began scrolling through his presentation. “So gas kills trees?” he said, sipping from his bottled water — the only kind of water he had drunk since the Woburn case.

Schlichtmann has a reputation for taking on cases that no one else would touch and marshaling the tremendous resources required to take on large corporations. Ackley’s case appealed to him, and it helped that a natural gas leak was suspected in another case he was working on. It might be good to have a guy like Ackley around, he thought. Schlichtmann said he’d look into it.

Ackley left feeling ecstatic. For nearly six months he’d been hitting dead ends with lawyers; now a high-flying attorney was interested. He carried on his usual Friday routine, playing sports at his local club and drinking with the guys. That night he stuck around longer than usual, and didn’t get home until 1am. When the phone rang at 7am the next day, Ackley was in the shower, still groggy from his revels. “Where have you been?” Schlichtmann said, impatiently. “I’ve been up all night researching this.”

The two met the next day at Schlichtmann’s house, where the lawyer described his plan to enlist nearby cities as plaintiffs against local utility companies. The case was risky, he explained to Ackley, and it would take a couple of years. Ackley wasn’t just blowing the whistle: he would be an expert witness who, along with a team of arborists and a plant pathologist, would compile data to support the cities’ case. And if the case failed, Ackley wouldn’t get paid.

He decided to take the leap, and started mapping leaks in nearly a dozen towns around Massachusetts. His sons pitched in during breaks from college and, after three years of surveying, things were looking good. By the end of 2010, five towns had filed suit against National Grid, the international gas and electricity corporation that owns Boston Gas Company, seeking $2 million for damage to trees. If Schlichtmann could convince a jury that the company had knowingly violated safety standards, the case could recoup two or three times as much in punitive damages.

To help make the case, Ackley mapped and monitored around 1,500 leaks in five Boston suburbs. The lawyer, meanwhile, dug up forgotten court cases in which gas companies had been successfully sued for damage to trees, some dating back to the 1920s. He also gathered internal documents from local utility companies that the New England Gas Workers Association had obtained through a public records request. The documents listed more than 20,000 gas leaks in Massachusetts; the oldest had been leaking since 1985.

But National Grid pushed back. The company questioned the evidence linking leaks and tree damage, and stressed that safety was its priority. Its lawyers fought hard. At one point they argued that a town, unlike a corporation, is not a person in the eyes of the law and so cannot sue. Even if the towns were to be considered people, added the lawyers, National Grid was not engaged in trade or commerce with them and so could not be liable for any damages.

Every time the case stalled, life got harder for Ackley. His savings, scraped together over the course of his working life, started to run out. In spring 2010, he took a job at a pawn shop to make ends meet. Working at Lowell Jewelry and Loan paid the bills, but it was a depressing place. Ackley spent each day in a booth lined with bulletproof glass. There was a gun by his right hand and a spare ammunition clip next to his left. In between was a police call button.

It wasn’t just fears over his personal security that ground Ackley down. He’d left his career as a gas company consultant to do the right thing; now, to keep himself afloat, he was profiting from the misfortune of people who had been forced to sell their possessions.

When he wasn’t working in the pawn shop, he carried on surveying the streets of Massachusetts for the case. He was out there one chilly Saturday morning in late 2010, checking trees in Newton, a wealthy suburb west of Boston that Schlichtmann hoped would join the lawsuit. As Ackley extracted the end of a gas meter from a tangle of tree roots, an Asian-American man approached with a young boy in tow and asked him what he was doing.

“I remember an article about you in the local newspaper,” the man said. “You’re the guy I read about.” He handed Ackley his business card. “We should talk about this more some time.”

The man was Nathan Phillips.

With his bicycle-powered computer and hand-cranked phone, Phillips was the biggest environmental nutbag Ackley had ever met. It seemed like they had little in common: Ackley had been to Tea Party rallies; Phillips advised a group of eco-activists who called themselves the Boston Tree Party.

Ackley didn’t have much time for global warming: the whole panic smelled of fancy people trying to take away fun from guys like him who loved big cars and powerboats. Al Gore’s movie An Inconvenient Truth had really ticked him off. Where did Gore, who lived in a 900-square-metre mansion, get off telling ordinary people to turn down their air conditioning?

He didn’t doubt that the planet was warming — New England’s ponds no longer froze in the winter like they used to — but he wasn’t convinced that humans were to blame. He’d heard arguments for natural climate cycles and volcanic activity, and they seemed equally plausible.

But in Ackley, Phillips saw a self-taught urban naturalist. Not long after they met, he invited Ackley to his office. When he came downstairs, Phillips found his visitor peering at a gas detector that he had inserted into the soil around the stump of a tree. Philips told him high winds had blown the tree over in a storm.

Ackley showed him the reading on his meter; natural gas was seeping into the soil. “It wasn’t the storm that killed your tree,” he said.

Ackley returned soon after to give an informal presentation to Phillips’ graduate students. It was a something new for Ackley: most of what he knew about Boston University students came from cruising the BU Beach, a strip of grass along the Charles River where undergrads sunbathed on warm afternoons. Now a dozen students hung on his words.

When Phillips read the Howarth paper, he sought Ackley’s advice on the controversial figures on leaks from distribution systems — the data the gas industry had attacked. The figures for leaks from urban pipes were far too low, Ackley told him. Phillips thought that a study of gas leaks under a major city could help resolve the issue. Why not Boston? Ackley wasn’t so interested in passing judgment on global warming, but the data would help bolster Schlichtmann’s lawsuit. And Phillips had a grant from a local environmental organisation, which would pay enough to let Ackley leave his job at the pawn shop. He signed on.

One Sunday morning in September 2011, I joined them on a surveying trip. They made for an odd couple. Phillips was driving Ackley’s car, a small Pontiac that the former Impala driver had grudgingly purchased to save gas. The professor was earnest and eager to learn; Ackley was his brassy self, constantly pulling gags. He had a fake pile of dog excrement on the floor of the car for unsuspecting passengers to step in, and he regularly expressed mock horror at Phillips’ driving, pencilling a running total of the academic’s errors straight on to the dashboard.

Nonetheless, for Phillips, it was an eye-opening experience. As they drove together, the professor learned how cryptic street markings could reveal the type of pipe that lay beneath the surface, or the size of a gas main. Ackley decoded other clues: narrow stretches of asphalt were signs of recent pipeline repairs; patches of dead grass might indicate gas, or merely the salt used to melt snow in the winter. Ganoderma, a fungal growth at the base of trees, and epicormic budding, small branches poking out of the trunk of a tree, were signs of gas damage. Gooey black soil, too, was a good bet for a gas leak.

To map what they found, Phillips and Ackley had acquired a piece of equipment called a Picarro Analyzer, a laser spectrometer that can detect gas leaks and plot methane levels on a Google map using GPS. Ackley wasn’t convinced by the technology. Instead, he stuck with his trusty low-tech tools: a paper map, a pink highlighter and his nose.

Ackley’s problems weren’t over that day. Schlichtmann’s court case continued to drag, and Ackley was battling his bank over rising interest rates on the two lines of credit that were keeping him afloat. Mandy was working six, sometimes seven days a week. But Phillips would later arrange a paid position at Boston University for Ackley as a practitioner in residence (“Are you fucking kidding me?” Ackley replied when asked if he wanted the job). And the surveying work in Boston would lead to better-paid leak studies in other cities. After so many hours in conversation with Phillips, Ackley was even beginning to change his mind about global warming.

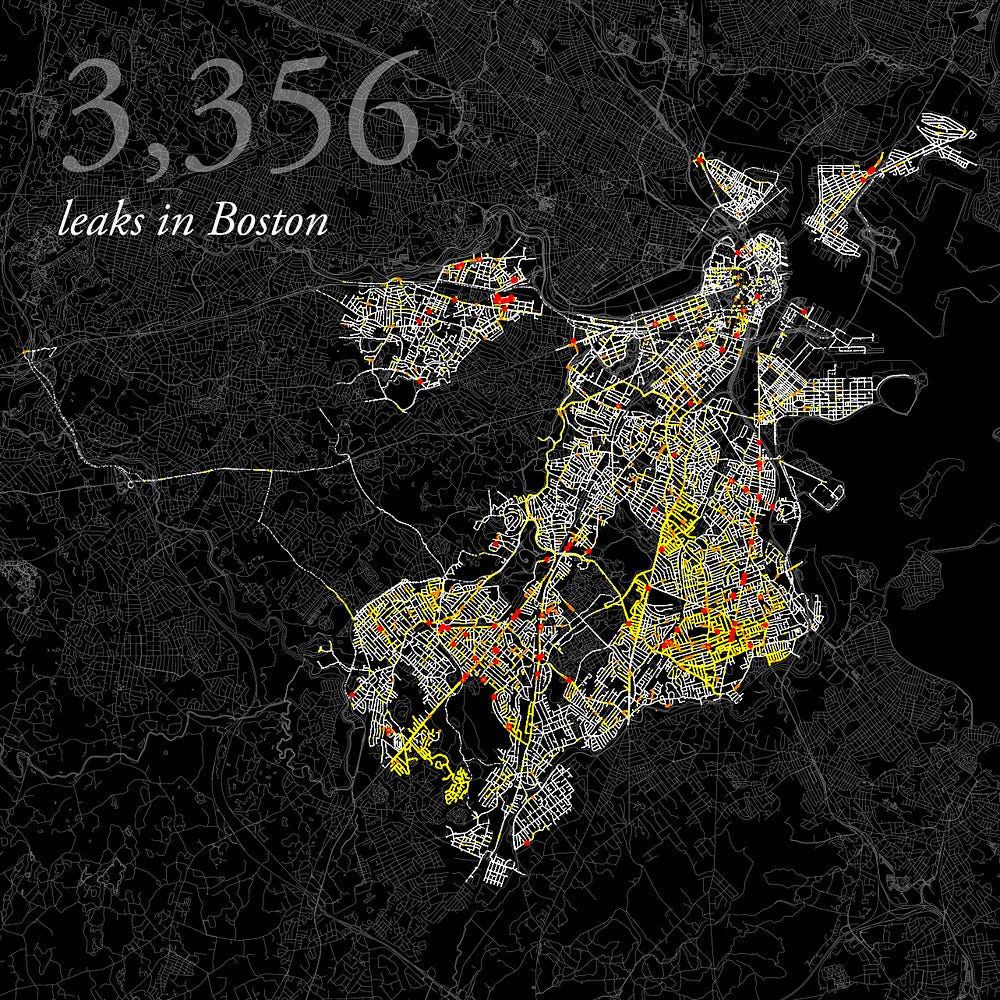

By the time they had finished surveying Boston, Phillips and Ackley had tallied 3,356 leaks. Their results appeared in the February 2013 issue of the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Pollution; Ackley’s name appears after Phillips’ on the paper, second in a list of nine authors. A satellite image of the Massachusetts State House and surrounding streets illustrates the study: a dozen gas leaks are represented as neon yellow spikes, many stretching taller than the gold-plated dome.

The images are dramatic, but it’s the numbers that really provide cause for concern. The baseline for atmospheric methane used in the study is just under two parts per million — a figure accepted by most experts as well within the range of naturally occurring gas levels. Large parts of Boston remain at this baseline, but Phillips and Ackley recorded elevated concentrations in many other areas. In some places they registered methane readings as high as 28 ppm, 15 times higher than normal.

National Grid responded to the study by pointing out that it is working with an old infrastructure and is replacing the state’s decrepit gas pipelines at a rate of 150 miles each year. And none of these levels, says the company, are high enough to cause an explosion. That is true: an explosion requires a much higher concentration of methane, although spot checks of several manholes by Ackley and Phillips did reveal concentrations above the explosive threshold.

But as Phillips and Ackley know, explosions are not the only hazard that methane poses. And if there are many more leaks than previously thought, what does that mean for the true impact of natural gas?

IN THE TWO YEARS SINCE Howarth and Ingraffea’s paper appeared, scientists have refined their attempts to compare natural gas with coal. Their progress has done little to ease concerns about methane. Last April, a team led by the Environmental Defense Fund, a widely-respected environmental organisation, concluded that gas is more damaging to the climate if just a shade more than three per cent of it escapes. That’s lower than the six per cent threshold identified by Howarth and Ingraffea. It’s also dangerously close to government leak figures — figures that the EDF said are uncertain.

There is also the issue of tipping points. Scientists often look a century ahead when thinking about the impact of greenhouse gases. But in recent years, many have come to fear that parts of our planet could already be undergoing irreversible change. When Arctic sea ice melts, for instance, it exposes a dark ocean surface that absorbs more sunlight than the ice, warming the region’s frigid waters and accelerating the melting. At some point, the positive feedback between melting and warming may become so great that the loss of the Arctic’s vast ice sheets will be inevitable.

It’s a fate that could be determined by the immediate warming impact of the gases we release to the atmosphere, and it is in the immediate future that methane is most dangerous.

These fears cannot be confirmed without knowing how much methane spills into the atmosphere. In the months they spent driving round Boston, Phillips and Ackley focused on counting leaks rather than measuring the volume of methane rising up from the city’s streets. Yet the sheer number of leaks they found is concerning. And the numbers are probably typical of America’s older cities.

“I think Philadelphia, New York, Washington DC and many other cities that have been plumbing natural gas for 100 years or more are likely as leaky,” says Rob Jackson, an environmental scientist at Duke University who helped Ackley and Phillips analyse the Boston data.

It is true that America’s east coast has an ailing infrastructure based largely on ageing and leaky cast iron pipes. One story that still circulates among gas workers maintains that until recently, parts of the pipeline relied on hollowed-out tree trunks that were put in place as a stopgap over a century ago. Over the years, the story goes, the trunks decomposed — leaving the gas to funnel through nothing more than the shadow left behind in the earth as the pipe rotted away.

Yet leaks are certainly not the exclusive problem of the first US cities. I have seen leak data collected by Ackley and others in cities across America, as well as in far older urban centres, such as London, Paris, Amsterdam and Istanbul. Without volume measurements, it is impossible to quantify the impact on climate change. But it is clear that gas leaks plague these cities. “This is absolutely not a Boston phenomenon,” says Mike Woelk, who heads up Picarro, the company that makes the testing technology that Phillips and Ackley use. “This is a global phenomenon. We find the same leak rates that you saw in Boston in cities worldwide.”

Thanks in large part to a whistle-blowing libertarian with an off-colour sense of humour, the true scale of the problem will soon be nailed down. Ackley himself has surveyed Manhattan, Washington, D.C. and the fracking fields of Pennsylvania in recent months. An EDF study will soon reveal the volume of methane that flows from Boston’s gas leaks. It is just one of roughly a dozen studies on methane emissions across the country that the organisation hopes to publish in the coming year. Industry is also involved: the American Gas Association told me that it is working with the EDF and others to develop more accurate means for measuring leaks.

Joe von Fischer, a scientist at Colorado State University who is working on one of the EDF studies, says that two people helped get this movement off the ground: Robert Howarth and Bob Ackley. “I didn’t really realise how widespread natural gas leaks are,” he added. “The ball is rolling, and its Bob’s ball.”

THIS JANUARY, TWO DAYS AFTER Barack Obama’s second inauguration, I joined Ackley as he drove through Anacostia, a neighbourhood of Washington, D.C. that is one of the poorest and most crime-ridden areas in America. He had spent the previous 18 days passing by D.C.’s most famous landmarks, from the National Mall, which turned out to have few leaks, to Embassy Row, which he described as “a total sieve”. As clean-up crews picked up the last of the debris from the throngs that had descended for the inauguration, we headed to a part of town where few outsiders venture.

Ackley was physically and mentally exhausted. He’d been staying in a cheap hotel and logging between 10 and 12 hours a day behind the wheel. The highlighter pens and worn-out atlases he had once relied on had been replaced by a computer mouse that he rolled up and down his right thigh. A new baseball cap, emblazoned with the Picarro logo, had replaced the one that had urged “Eat, Sleep, Fish”.

The search for leaks took us past rows of boarded-up apartment buildings. As we approached a corner that was home to a Pentecostal church and a pair of liquor stores, the methane concentrations rose to four parts per million, more than twice background levels. There were similar pockets all across the city. “I’ve never seen so many gas leaks in my life,” Ackley said.

We drove all morning, up and down residential streets, sometimes circling the same block several times to hit every spot. In a few more hours Ackley would finish mapping the city, completing the job in time to make it home and attend his youngest daughter’s college graduation.

At lunchtime we pulled into Johnny Boy Ribs, a carry-out restaurant where the staff served customers from behind bulletproof glass. As we sat in the car outside, eating thick, sticky ribs sandwiched between stale white bread, Ackley mused about what he would do with his free time if he still had his old job. “Maybe golf and drink and play bridge,” he said.

His legs ached from the weeks spent behind the wheel, but he was talking excitedly about the surveys he had lined up and the plans he had. He’d spent a career coasting; now he was doing the same work but with a real mission. It made him feel good.

Ackley told me that he had recently heard from Schlichtmann. After all the delays, National Grid, which continues to reject the allegations against it, had finally started deposing witnesses for the lawsuit. Yet Ackley’s focus seemed to be elsewhere. The outcome of the lawsuit — the thing that he’d once pinned so many hopes on — didn’t seem so crucial any more. He was bringing gas leaks to the attention of the world’s climate scientists, and carving out an unconventional place among them. He took a bite out of his sandwich, and smiled. “I’ve already won,” he said.

This story was written by Phil McKenna, edited by Bobbie Johnson with assistance from Dan Baum and Margaret Knox, fact-checked by Gillian Conahan, and copy-edited by Kate Bevan. The maps were by Eric Fischer, photographs by Bryce Vickmark and the audiobook was narrated by Ian Parkinson.

Follow Matter on Twitter | Like us on Facebook | Subscribe to our newsletter

This piece was awarded the 2013 AAAS Kavli award for science journalism, and the 2014 NASW Science in Society Award.