The Secrets of Bezos: How Amazon Became the Everything Store

Amazon.com rivals Wal-Mart as a store, Apple as a device maker, and IBM as a data services provider. It will rake in about $75 billion this year. For his book, Bloomberg Businessweek’s Brad Stone spoke to hundreds of current and former friends of founder Jeff Bezos. In the process, he discovered the poignant story of how Amazon became the Everything Store.

Within Amazon.com there’s a certain type of e-mail that elicits waves of panic. It usually originates with an annoyed customer who complains to the company’s founder and chief executive officer. Jeff Bezos has a public e-mail address, jeff@amazon.com. Not only does he read many customer complaints, he forwards them to the relevant Amazon employees, with a one-character addition: a question mark.

When Amazon employees get a Bezos question mark e-mail, they react as though they’ve discovered a ticking bomb. They’ve typically got a few hours to solve whatever issue the CEO has flagged and prepare a thorough explanation for how it occurred, a response that will be reviewed by a succession of managers before the answer is presented to Bezos himself. Such escalations, as these e-mails are known, are Bezos’s way of ensuring that the customer’s voice is constantly heard inside the company.

One of the more memorable escalations occurred in late 2010. It had come to Bezos’s attention that customers who had browsed the lubricants section of Amazon’s sexual wellness category were receiving personalized e-mails pitching a variety of gels and other intimacy facilitators. When the e-mail marketing team received the question mark, they knew the topic was delicate and nervously put together an explanation. Amazon’s direct marketing tool was decentralized, and category managers could generate e-mail campaigns to customers who had looked at certain product categories but did not make purchases. The promotions tended to work; they were responsible for hundreds of millions of dollars in Amazon’s annual sales. In the matter of the lubricant e-mail, though, a low-level product manager had overstepped the bounds of propriety. But the marketing team never got the chance to send this explanation. Bezos demanded to meet in person.

At Amazon’s Seattle headquarters, Jeff Wilke, the senior vice president for North American retail, Doug Herrington, the vice president for consumables, and Steven Shure, the vice president for worldwide marketing, waited in a conference room until Bezos glided in briskly. He started the meeting with his customary, “Hello, everybody,” and followed with “So, Steve Shure is sending out e-mails about lubricants.”

Bezos likes to say that when he’s angry, “just wait five minutes,” and the mood will pass like a tropical squall. Not this time. He remained standing. He locked eyes with Shure, whose division oversaw e-mail marketing. “I want you to shut down the channel,” he said. “We can build a $100 billion company without sending out a single f------ e-mail.”

An animated argument followed. Amazon’s culture is notoriously confrontational, and it begins with Bezos, who believes that truth shakes out when ideas and perspectives are banged against each other. Wilke and his colleagues argued that lubricants were available in supermarkets and drugstores and were not that embarrassing. They also pointed out that Amazon generated a significant volume of sales with such e-mails. Bezos didn’t care; no amount of revenue was worth jeopardizing customer trust. “Who in this room needs to get up and shut down the channel?” he snapped.

Eventually, they compromised. E-mail marketing would be terminated for certain categories such as health and personal care. The company also decided to build a central filtering tool to ensure that category managers could no longer promote sensitive products, so matters of etiquette were not subject to personal taste. For books and electronics and everything else Amazon sold, e-mail marketing lived to fight another day.

Amazon employees live daily with these kinds of fire drills. “Why are entire teams required to drop everything on a dime to respond to a question mark escalation?” an employee once asked at the company’s biannual meeting held at Seattle’s KeyArena, a basketball coliseum with more than 17,000 seats. “Every anecdote from a customer matters,” Wilke replied. “We research each of them because they tell us something about our processes. It’s an audit that is done for us by our customers. We treat them as precious sources of information.”

It’s one of the contradictions of life inside Amazon: The company relies on metrics to make almost every important decision, such as what features to introduce or kill, or whether a new process will root out an inefficiency in its fulfillment centers. Yet random customer anecdotes, the opposite of cold, hard data, can also alter Amazon’s course.

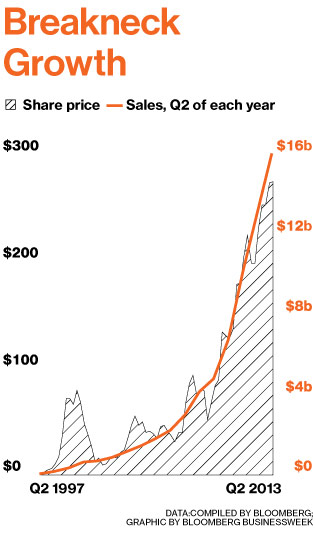

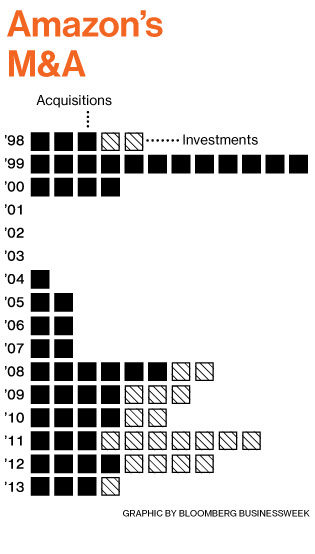

It’s easy to forget that until recently, people thought of Amazon primarily as an online bookseller. Today, as it nears its 20th anniversary, it’s the Everything Store, a company with around $75 billion in annual revenue, a $140 billion market value, and few if any discernible limits to its growth. In the past few months alone, it launched a marketplace in India, opened a website to sell high-end art, introduced another Kindle reading device and three tablet computers, made plans to announce a set-top box for televisions, and funded the pilot episodes of more than a dozen TV shows. Amazon’s marketplace hosts the storefronts of countless smaller retailers; Amazon Web Services handles the computer infrastructure of thousands of technology companies, universities, and government agencies.

Bezos, 49, has a boundless faith in the transformative power of technology. He constantly reinvests Amazon’s profits to improve his existing businesses and explore new ones, often to the consternation of shareholders. He surprised the world in August when he personally bought the Washington Post newspaper, saying his blend of optimism, innovation, and long-term orientation could revive it. One day a week, he moonlights as the head of Blue Origin, his private rocket ship company, which is trying to lower the cost of space travel.

Amazon has a few well-known peculiarities—the desks are repurposed doors; meetings begin with everyone in the room sitting in silence as they read a six-page document called a narrative. It’s a famously demanding place to work. And yet just how the company works—and what Bezos is like as a person—is difficult to know.

Bezos rarely speaks at conferences and gives interviews only to publicize new products, such as the latest Kindle Fire. He declined to comment on this account, saying that it’s “too early” for a reflective look at Amazon’s history, though he approved many interviews with friends, family, and senior Amazon executives. John Doerr, the venture capitalist who backed Amazon early and was on its board of directors for a decade, calls Amazon’s Berlin Wall approach to public relations “the Bezos Theory of Communicating.” It’s really just a disciplined form of editing. Bezos takes a red pen to press releases, product descriptions, speeches, and shareholder letters, crossing out anything that doesn’t convey a simple message: You won’t find a cheaper, friendlier place to get everything you need than Amazon.

The one unguarded thing about Bezos is his laugh—a pulsing, mirthful bray that he leans into while craning his neck back. He unleashes it often, even when nothing is obviously funny to anyone else. And it startles people. “You can’t misunderstand it,” says Rick Dalzell, Amazon’s former chief information officer, who says Bezos often wields his laugh when others fail to meet his lofty standards. “It’s disarming and punishing. He’s punishing you.”

Intensity is hardly rare among technology CEOs. Steve Jobs was as famous for his volatility with Apple subordinates as he was for the clarity of his insights about customers. He fired employees in the elevator and screamed at underperforming executives. Bill Gates used to throw epic tantrums at Microsoft; Steve Ballmer, his successor, had a propensity for throwing chairs. Andy Grove, the former CEO of Intel, was so harsh and intimidating that a subordinate once fainted during a performance review.

Bezos fits comfortably into this mold. His drive and boldness trumps other leadership ideals, such as consensus building and promoting civility. While he can be charming and capable of great humor in public, in private he explodes into what some of his underlings call nutters. A colleague failing to meet Bezos’s exacting standards will set off a nutter. If an employee does not have the right answers or tries to bluff, or takes credit for someone else’s work, or exhibits a whiff of internal politics, uncertainty, or frailty in the heat of battle—a blood vessel in Bezos’s forehead bulges and his filter falls away. He’s capable of hyperbole and harshness in these moments and over the years has delivered some devastating rebukes. Among his greatest hits, collected and relayed by Amazon veterans:

“Are you lazy or just incompetent?”

“I’m sorry, did I take my stupid pills today?”

“Do I need to go down and get the certificate that says I’m CEO of the company to get you to stop challenging me on this?”

“Are you trying to take credit for something you had nothing to do with?”

“If I hear that idea again, I’m gonna have to kill myself.”

“We need to apply some human intelligence to this problem.”

[After reviewing the annual plan from the supply chain team] “I guess supply chain isn’t doing anything interesting next year.”

[After reading a start-of-meeting memo] “This document was clearly written by the B team. Can someone get me the A team document? I don’t want to waste my time with the B team document.”

[After an engineer’s presentation] “Why are you wasting my life?”

Some Amazon employees advance the theory that Bezos, like Jobs, Gates, and Oracle co-founder Larry Ellison, lacks empathy. As a result, he treats workers as expendable resources without taking into account their contributions. That in turn allows him to coldly allocate capital and manpower and make hyperrational business decisions, where another executive might let emotion and personal relationships figure into the equation. They also acknowledge that Bezos is primarily consumed with improving the company’s performance and customer service and that personnel issues are secondary. “This is not somebody who takes pleasure at tearing someone a new a--hole,” says Kim Rachmeler, an executive who worked at Amazon for more than a decade. “He is not that kind of person. Jeff doesn’t tolerate stupidity, even accidental stupidity.”

To the amazement and irritation of employees, Bezos’s criticisms are almost always on target. Bruce Jones, a former Amazon supply chain vice president, describes leading a five-engineer team figuring out ways to make the movement of workers in fulfillment centers more efficient. The group spent nine months on the task, then presented their work to Bezos. “We had beautiful documents, and everyone was really prepared,” Jones says. Bezos read the paper, said, “You’re all wrong,” stood up, and started writing on the whiteboard.

“He had no background in control theory, no background in operating systems,” Jones says. “He only had minimum experience in the distribution centers and never spent weeks and months out on the line.” But Bezos laid out his argument on the whiteboard, and “every stinking thing he put down was correct and true,” Jones says. “It would be easier to stomach if we could prove he was wrong, but we couldn’t. That was a typical interaction with Jeff. He had this unbelievable ability to be incredibly intelligent about things he had nothing to do with, and he was totally ruthless about communicating it.”

Jones cites another example. In 2002, Amazon changed the way it accounted for inventory, from the last-in first-out, or LIFO, system to first-in first-out, or FIFO. The change allowed Amazon to better distinguish between its own inventory and the inventory that was owned and stored in fulfillment centers by partners such as Toys “R” Us and Target. Jones’s supply chain team was in charge of this complicated effort, and its software, riddled with bugs, created a few difficult days during which Amazon’s systems were unable to recognize any revenue. On the third day, Jones was giving an update on the transition when Bezos had a nutter. “He called me a ‘complete f------ idiot’ and said he had no idea why he hired idiots like me at the company, and said, ‘I need you to clean up your organization,’ ” Jones recalls. “It was brutal. I almost quit. I was a resource of his that failed. An hour later he would have been the same guy as always, and it would have been different. He can compartmentalize like no one I’ve ever seen.”

Amazon has a clandestine group with a name worthy of a James Bond film: Competitive Intelligence. The team, which operated for years within the finance department under longtime executives Tim Stone and Jason Warnick, focuses in part on buying large volumes of merchandise from other online retailers and measuring the quality and speed of their services—how easy it is to buy, how fast the shipping is, and so forth. The mandate is to investigate whether any rival is doing a better job than Amazon and then present the data to a committee of Bezos and other senior executives, who ensure that the company addresses any emerging threat and catches up quickly.

In the late 2000s, Competitive Intelligence began tracking a rival with an odd name and a strong rapport with female shoppers. Quidsi (Latin for “what if”) was a Jersey City company better known for its website Diapers.com. Grammar school friends Marc Lore and Vinit Bharara founded the startup in 2005 to allow sleep-deprived caregivers to painlessly schedule recurring shipments of vital supplies. By 2008 the company had expanded into selling baby wipes, infant formula, clothes, strollers, and other survival gear for new parents. In an October 2010 Bloomberg Businessweek cover story, the Quidsi founders admitted to studying Amazon closely and idolizing Bezos. In private conversations, they referred to Bezos as “sensei.”

In 2009, Jeff Blackburn, Amazon’s senior vice president for business development, ominously informed the Quidsi co-founders over an introductory lunch that the e-commerce giant was getting ready to invest in the category and that the startup should think seriously about selling to Amazon. According to conversations with insiders at both companies, Lore and Bharara replied that they wanted to remain private and build an independent company. Blackburn told the Quidsi founders that they should call him if they ever reconsidered.

Soon after, Quidsi noticed Amazon dropping prices up to 30 percent on diapers and other baby products. As an experiment, Quidsi executives manipulated their prices and then watched as Amazon’s website changed its prices accordingly. Amazon’s pricing bots—software that carefully monitors other companies’ prices and adjusts Amazon’s to match—were tracking Diapers.com.

At first, Quidsi fared well despite Amazon’s assault. Rather than attempting to match Amazon’s low prices, it capitalized on the strength of its brand and continued to reap the benefits of strong word of mouth. After a while, the heated competition took a toll on the company. Quidsi had grown from nothing to $300 million in annual sales in just a few years, but with Amazon focusing on the category, revenue growth started to slow. Venture capitalists were reluctant to furnish Quidsi with additional capital, and the company was not yet mature enough for an initial public offering. For the first time, Lore and Bharara had to think about selling.

Meanwhile, Wal-Mart Stores was looking for ways to make up ground it had lost to Amazon and was shaking up its online division. Wal-Mart’s then-vice chairman, Eduardo Castro-Wright, took over Walmart.com, and one of his first calls was to Lore to initiate acquisition talks. Lore said Quidsi wanted to get close to “Zappos money”—more than $500 million, plus additional bonuses spread out over many years tied to performance goals. Wal-Mart agreed in principle and started due diligence. Mike Duke, Wal-Mart’s CEO, visited a Diapers.com fulfillment center in New Jersey. The formal offer from Bentonville was around $450 million—nowhere near Zappos money.

So Lore picked up the phone and called Amazon. In September 2010, he and Bharara traveled to Seattle to discuss the possibility of Amazon acquiring Quidsi. While they were in that early morning meeting with Bezos, Amazon sent out a press release introducing a service called Amazon Mom. It was a sweet deal for new parents: They could get up to a year’s worth of free two-day Prime shipping (a program that usually cost $79 a year). Customers also could get an additional 30 percent off the already-discounted diapers if they signed up for regular monthly deliveries as part of a service called Subscribe and Save. Back in New Jersey, Quidsi employees desperately tried to call their founders to discuss a public response to Amazon Mom. The pair couldn’t be reached: They were still in the meeting at Amazon’s headquarters.

Quidsi could now taste its own blood. At one point, Quidsi executives took what they knew about shipping rates, factored in Procter & Gamble’s wholesale prices, and calculated that Amazon was on track to lose $100 million over three months in the diaper category alone.

Inside Amazon, Bezos rationalized these moves as being in the company’s long-term interest of delighting its customers and building its consumables business. He told Peter Krawiec, the business development vice president, not to spend more than a certain amount to buy Quidsi but to make sure that Amazon did not, under any circumstance, lose the deal to Wal-Mart.

As a result of Bezos’s meeting with Lore and Bharara, Amazon had an exclusive three-week period to study Quidsi’s financial results and come up with an offer. At the end of that period, Krawiec offered Quidsi $540 million and called the number a “stretch price.” Knowing that Wal-Mart hovered on the sidelines, he gave Quidsi a window of 48 hours to respond and made it clear that if the founders didn’t take the offer, the Amazon Mom onslaught would continue.

Wal-Mart should have had a natural advantage. Jim Breyer, the managing partner at one of Quidsi’s venture capital backers, Accel, was also on the Wal-Mart board. But Wal-Mart was caught flat-footed. By the time it increased its offer to $600 million, Quidsi had tentatively accepted the Amazon term sheet. Duke left phone messages for several Quidsi board members, imploring them not to sell to Amazon. Those messages were then transcribed and sent to Seattle, because Amazon had stipulated in the preliminary term sheet that Quidsi turn over information about any subsequent offer.

When Bezos’s lieutenants learned of Wal-Mart’s counterbid, they ratcheted up the pressure, telling the Quidsi founders that “sensei” was such a furious competitor that he would drive diaper prices to zero if they sold to Bentonville. The Quidsi board convened to discuss the possibility of letting the Amazon deal expire and then resuming negotiations with Wal-Mart. But by then, Bezos’s Khrushchev-like willingness to use the thermonuclear option had had its intended effect. The Quidsi executives stuck with Amazon, largely out of fear. The deal was announced on Nov. 8, 2010.

Blackburn, Amazon’s mergers-and-acquisitions chief, said in a 2012 interview that everything the company did in the diapers market was planned beforehand and was unrelated to competing with Quidsi. He said that Quidsi was similar to shoe retailer Zappos, which Amazon acquired in 2009: a “stubbornly independent company building an extremely flexible franchise.”

The Federal Trade Commission scrutinized the acquisition for four and a half months, going beyond the standard review to the second-request phase, where companies must provide more information about a transaction. The deal raised a host of red flags, such as the elimination of a major player in a competitive category, according to an FTC official familiar with the review. The merger was eventually approved, in part because it did not result in a monopoly. Costco Wholesale, Target, and plenty of other companies sold diapers online and off.

Bezos won, neutralizing an incipient competitor and filling another set of shelves in his Everything Store. Quidsi soon expanded into pet supplies with Wag.com and toys with Yoyo.com. Wal-Mart missed the chance to acquire a talented team of entrepreneurs who’d gone toe to toe with Amazon in a new product category. And insiders were once again left marveling at how Bezos had engineered another acquisition by driving his target off a cliff.

The people who do well at Amazon are often those who thrive in an adversarial atmosphere with almost constant friction. Bezos abhors what he calls “social cohesion,” the natural impulse to seek consensus. He’d rather his minions battle it out backed by numbers and passion, and he has codified this approach in one of Amazon’s 14 leadership principles—the company’s highly prized values that are often discussed and inculcated into new hires:

Have Backbone; Disagree and Commit

Leaders are obligated to respectfully challenge decisions when they disagree, even when doing so is uncomfortable or exhausting. Leaders have conviction and are tenacious. They do not compromise for the sake of social cohesion. Once a decision is determined, they commit wholly.

Some employees love this confrontational culture and find they can’t work effectively anywhere else. “Everybody knows how hard it is and chooses to be there,” says Faisal Masud, who spent five years in the retail business. “You are learning constantly, and the pace of innovation is thrilling. I filed patents; I innovated. There is a fierce competitiveness in everything you do.” The professional networking site LinkedIn is full of “boomerangs”—Amazon-speak for executives who left the company and then returned.

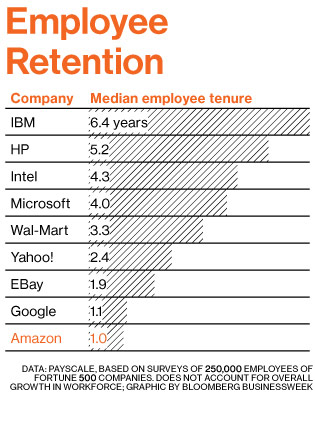

But other alumni call Amazon’s internal environment a “gladiator culture” and wouldn’t think of returning. Many last less than two years. “It’s a weird mix of a startup that is trying to be supercorporate and a corporation that is trying hard to still be a startup,” says Jenny Dibble, who was a marketing manager there for five months in 2011. She found her bosses were unreceptive to her ideas about using social media and that the long hours were incompatible with raising a family. “It was not a friendly environment,” she says. Even leaving Amazon can be a combative process—the company is not above sending letters threatening legal action if an employee takes a similar job at a competitor. Masud, who left Amazon for EBay in 2010, received such a threat. (EBay resolved the matter privately.)

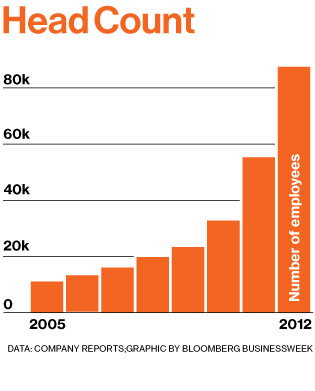

Employee churn doesn’t seem to damage Amazon, though. The company, aided by the appeal of its steadily increasing stock price, is an accomplished recruiter of talent. In its second-quarter earnings report in July, Amazon said its ranks had swelled to 97,000 full-time and part-time employees, up 40 percent from the year before. New hires are given an industry-average base salary, a signing bonus spread over two years, and a grant of restricted stock units spread over four years. Unlike Google and Microsoft, whose stock grants vest evenly year by year, Amazon backloads the vesting toward the end of the four-year period. Employees typically get 5 percent of their shares at the end of their first year, 15 percent their second year, and then 20 percent every six months over the final two years. Ensuing grants vest over two years and are also backloaded to ensure that employees keep working hard and are never inclined to coast.

Managers in departments of 50 people or more are often required to “top-grade” their subordinates on a curve and must dismiss the least effective performers. As a result, many Amazon employees live in perpetual fear; those who manage to get a positive review are often genuinely surprised.

There are few perks or unexpected performance bonuses at Amazon, though the company is more generous than it was the 1990s, when Bezos refused to give employees city bus passes because he didn’t want to give them any reason to rush out of the office to catch the last bus of the day. Employees now get cards that entitle them to free rides on Seattle’s regional transit system. Parking at the company’s offices in South Lake Union costs $220 a month, and Amazon reimburses employees—for $180. Conference room tables are a collection of blond-wood door-desks shoved together side by side. The vending machines take credit cards, and food in the company cafeterias is not subsidized. New hires get a backpack with a power adapter, a laptop dock, and orientation materials. When they resign, they’re asked to hand in all that equipment—including the backpack. These practices are also embedded in the sacrosanct leadership principles:

Frugality

We try not to spend money on things that don’t matter to customers. Frugality breeds resourcefulness, self-sufficiency, and invention. There are no extra points for head count, budget size, or fixed expense.

Bezos molded Amazon’s business principles through two decades of surviving in the thin atmosphere of low profit margins and fierce skepticism from the outside world. In a way, the entire company is built around his brain—an amplification machine meant to disseminate his ingenuity and drive across the greatest possible radius. “It’s scaffolding to magnify the thinking embodied by Jeff,” says Wilke, the senior vice president for North American retail. “Jeff was learning as he went along. He learned things from each of us who had expertise and incorporated the best pieces into his mental model. Now everyone is expected to think as much as they can like Jeff.”

Bezos runs the final meetings in the biannual operating reviews, dubbed OP1 (held over the summer) and OP2 (after the holidays). Teams work intensely for months preparing for their sessions with the CEO, drawing up six-page narratives that spell out their plans for the year ahead. A few years ago, the company refined this process further to make the narratives more easily digestible for Bezos and other members of his senior leadership group, called the S Team, who cycle through many topics during these reviews. Now every narrative includes at the top of the page a list of a few rules, called tenets, that guide the group’s hard decisions and allow it to move fast, without constant supervision.

Once a week, usually on Tuesdays, various departments meet with their managers to review spreadsheets of data important to their business. Customer anecdotes have no place at these meetings; numbers alone must demonstrate what’s working and what’s broken, how customers are behaving, and ultimately how well the company overall is performing. “This is what, for employees, is so absolutely scary and impressive about the executive team. They force you to look at the numbers and answer every single question about why specific things happened,” says Dave Cotter, who spent four years at Amazon as a general manager in various divisions. “Because Amazon has so much volume, it’s a way to make very quick decisions and not get into subjective debates. The data doesn’t lie.”

The metrics meetings culminate every Wednesday with the Weekly Business Review, one of the company’s most important rituals, which is run by Wilke. Sixty managers in the retail business gather in one room to discuss their departments, share data about defects and inventory turns, and talk about forecasts and the complex interactions between different parts of the company.

Bezos does not attend these meetings. He spends more time on Amazon’s newer businesses, such as Amazon Web Services, the streaming video and music initiatives, and, in particular, the Kindle and Kindle Fire efforts. (Executives joke darkly that employees can’t even pass gas in the Kindle buildings without the CEO’s permission.) But Bezos can always make his presence felt anywhere in the company.

After the lubricant fracas of 2010, for example, e-mail marketing fell squarely under his purview. He carefully monitored efforts to filter the kinds of messages that could be sent to customers, and he tried to think about the challenge of e-mail outreach in fresh ways. Then, in late 2011, he had what he considered to be a significant new idea.

Bezos is a fan of e-mail newsletters such as veryshortlist.com, a daily assortment of cultural tidbits from the Web, and Cool Tools, a compendium of technology tips and product reviews written by Kevin Kelly, a co-founder of Wired. Both are short, well-written, and informative. Perhaps, Bezos reasoned, Amazon should be sending a single well-crafted e-mail every week—a short digital magazine—instead of a succession of bland, algorithm-generated marketing pitches. He asked Shure, the marketing vice president, to explore the idea.

From late 2011 through early 2012, Shure’s group presented a variety of concepts to Bezos. One version revolved around celebrity Q&As, another highlighted interesting historical facts about products. The project never progressed—it fared poorly in tests with customers—and several participants remember the process as being particularly excruciating. In one meeting, Bezos quietly thumbed through the mock-ups as everyone waited in silence. “Here’s the problem with this,” Bezos said, according to people who were present. “I’m already bored.” He liked the last concept the most, which suggested profiling a selection of products that were suddenly hot, such as Guy Fawkes masks and CDs by the Grammy-winning British singer Adele. “But the headlines need to be punchier,” he told the group, which included the writers of the material. “And some of this is just bad writing. If you were doing this as a blogger, you would starve.”

Finally he turned his attention to Shure, who, like so many other marketing vice presidents throughout Amazon’s history, was an easy target.

“Steve, why haven’t I seen anything on this in three months?”

“Well, I had to find an editor and work through mock-ups.”

“This is developing too slow. Do you care about this?”

“Yes, Jeff, we care.”

“Strip the design down, it’s too complicated. Also, it needs to move faster!”

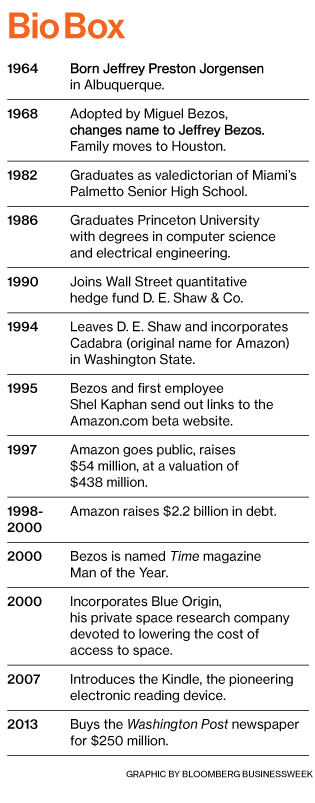

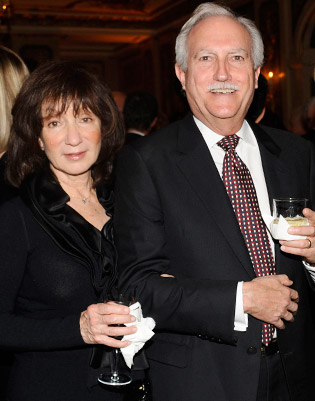

Jeff Bezos grew up in a tight-knit family, with two deeply involved and caring parents, Jackie and Mike, and two close younger siblings, Christina and Mark. Jackie, who gave birth to Bezos just two weeks after she turned 17, was a towering figure of authority to Bezos and his friends. Mike, also known as Miguel, was a Cuban immigrant who arrived in America at age 18, alone and penniless, knowing only one English word: hamburger. Through grit and determination, he got a college education and climbed through the ranks of Exxon as a petroleum engineer and manager, in a career that took the Bezos family to Houston, Pensacola, Fla., Miami, and, after Bezos left for college, cities in Europe and South America.

Yet for a brief period early in his life, before this ordinary if peripatetic childhood, Bezos lived alone with his mother and grandparents. And before that, he lived with his mother and his biological father, a man named Ted Jorgensen. Bezos has said the only time he thinks about Jorgensen is when he’s filling out a medical form that asks for his family history. He told Wired in 1999 that he’d never met the man. Strictly speaking, that’s not true: Bezos last saw him when he was 3 years old. And while Bezos’s professional life has been closely studied and celebrated over the last two decades, this story has never been told.

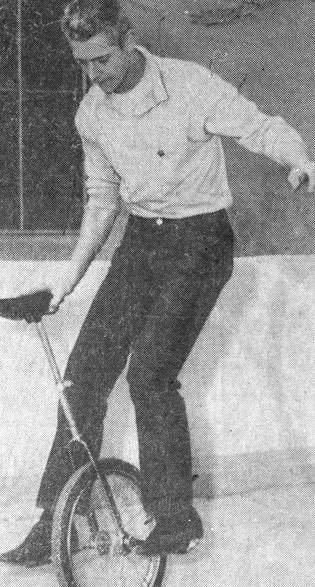

Jorgensen was a circus performer and one of Albuquerque’s best unicyclists in the 1960s. A newspaper photograph taken in 1961, when he was 16, shows him standing on the pedals of his unicycle facing backward, one hand on the seat, the other splayed theatrically to the side, his expression tense with concentration. The caption says he was awarded “most versatile rider” in the local unicycle club.

That year, Jorgensen and a half-dozen other riders traveled the country playing unicycle polo in a team managed by Lloyd Smith, the owner of a local bike shop. Jorgensen’s team was victorious in places such as Newport Beach, Calif., and Boulder, Colo. The Albuquerque Tribune has an account of the event: Four hundred people showed up at a shopping center parking lot in freezing weather to watch the teams swivel around in four inches of snow wielding three-foot-long plastic mallets in pursuit of a six-inch rubber ball. Jorgensen’s team swept a doubleheader, 3 to 2 and 6 to 5.

In 1963, Jorgensen’s troupe resurfaced as the Unicycle Wranglers, touring county fairs, sporting events, and circuses. They square-danced, did the jitterbug and the twist, skipped rope, and rode on a high wire. The group practiced constantly, rehearsing three times a week at Smith’s shop and taking dance classes twice a week. “It’s like balancing on greased lightning and dancing all at the same time,” one member told the Tribune. When the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus came to town, the Wranglers performed under the big top, and in the spring of 1965 they performed in eight local shows of the Rude Brothers Circus.

Jorgensen was born in 1944 in Chicago to a family of Baptists. His father moved the family to Albuquerque when Jorgensen and his younger brother, Gordon, were in elementary school. Ted’s father took a job as a purchase agent at Sandia Base (today’s Sandia National Laboratories), then the largest nuclear weapons installation in the country, handling the procurement of supplies at the base.

In high school, Jorgensen started dating Jacklyn Gise, a girl two years his junior whose father also worked at Sandia Base. Their dads knew each other. Her father, Lawrence Preston Gise, known to friends as Preston and to his family as Pop, ran the local office of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, the federal agency that managed the nuclear weapons program after Harry S Truman took it from the military following World War II.

Jorgensen was 18 and finishing his senior year in high school when Gise became pregnant. She was a sophomore. They were in love and decided to get married. Her parents gave them money to fly to Juárez, Mexico, for a ceremony. A few months later, on July 19, 1963, they repeated their vows at the Gises’ house. Because she was underage, both of their mothers signed the application for a marriage license. The baby was born on Jan. 12, 1964. They named him Jeffrey Preston Jorgensen.

The new parents rented an apartment in Albuquerque’s Southeast Heights neighborhood. Jackie finished high school, and during the day, her mother, Mattie, took care of the baby. Life was difficult. Jorgensen was perpetually broke, and they had only one car, his cream-colored ’55 Chevy. Belonging to a unicycle troupe didn’t pay much. The Wranglers divided their fees among all members, with Smith taking a generous cut off the top. Eventually, Jorgensen got a $1.25-an-hour job at the Globe Department Store, part of Walgreen’s short-lived foray into the promising discount retail market being pioneered at the time by Kmart and Wal-Mart. Occasionally Jackie brought the baby to the store to visit.

Their marriage was probably doomed from the start. Jorgensen had a habit of drinking too much and staying out too late. He was an inattentive dad and husband. Jackie’s father tried to help him; he paid his son-in-law’s tuition at the University of New Mexico, but Jorgensen dropped out after a few semesters. Preston Gise then tried to get Jorgensen a job with the New Mexico State Police, but Jorgensen wasn’t interested.

Eventually, Jackie took the child and moved back in with her parents at Sandia. In June 1965, when the baby was 17 months old, she filed for divorce. The court ordered Ted to pay $40 a month in child support. Court records indicate that his income at the time was $180 a month. Over the next few years, he visited his son occasionally but missed many support payments.

Then Jackie took a job working in the bookkeeping department of the Bank of New Mexico and met Miguel Bezos, who was working the overnight shift while he attended the University of Albuquerque. On several occasions when Ted was visiting his son, Bezos would be there, and they avoided each other. But Ted asked around and heard he was a good man.

In 1968, Jackie called Ted and told him she was marrying Miguel and moving to Houston. She told him he could stop paying child support and asked him not to interfere in their lives. Her father confronted him and made him promise to stay away. Jackie also wanted to give Jeffrey her new husband’s surname and let Miguel adopt him. Ted’s permission was needed for the adoption. After thinking it over and reasoning that the boy would probably have a better life as the son of Jackie and her new husband, Ted obliged. After a few years, he lost track of the family and then forgot their last name.

If you were to search the world for the polar opposite of sprawling, secretive, powerful Amazon, you might arrive at a small bike shop in Glendale, Ariz., just north of Phoenix. It’s called the Roadrunner Bike Center. It sits in a shoebox-shape space in an ordinary shopping center next to the Hot Cutz Salon & Spa and down a ways from a Walmart grocery store. It offers a small selection of premium BMX and dirt bikes from companies such as Giant, Haro, and Redline, brands that carefully select their retail partners and generally do not sell to websites or discount outlets. “The old guy that runs this is always there and you can tell he loves to fix and sell bikes,” writes one customer in a typically favorable online review of the store. “When you buy from him he will take care of you. He also is the cheapest place I have ever taken a bike for a service, I think sometimes he runs a special for $30! That’s insane!”

A red poster board with the hand-scrawled words, “Layaway for the holidays!” leans against the window. Hanging on a wall next to the front counter, there’s a framed newspaper clipping with a photograph of a 16-year-old boy with a flattop haircut, standing up on the pedals of his unicycle, one hand on the seat and the other flared daringly out to the side.

I found Ted Jorgensen, Jeff Bezos’s biological father, behind the counter of his bike shop in late 2012. I’d considered a number of ways he might react to my unannounced appearance but gave a very low probability to the likelihood of what actually happened: He had no idea what I was talking about. Jorgensen said he didn’t know who Jeff Bezos was and was baffled by my suggestion that he was the father of this famous CEO.

I mentioned Jacklyn Gise and Jeffrey, the son they had during their brief teenage marriage. The old man’s face flushed with recognition. “Is he still alive?” he asked, not yet fully comprehending.

“Your son is one of the most successful men on the planet,” I told him. I showed him some Internet photographs on my smartphone, and for the first time in 45 years, Jorgensen saw his biological son. His eyes filled with sorrow and disbelief.

I took Jorgensen and his wife, Linda, to a steak dinner, and his story tumbled out. When the Bezos family moved from Albuquerque to Houston in 1968 and Jorgensen promised Jackie and her father that he would stay out of their lives, he remained in Albuquerque. He performed with his troupe and took odd jobs. He drove an ambulance and worked as an installer for Western Electric, a local utility.

In his twenties, he moved to Hollywood to help Smith, the Wranglers’ manager, start a new bike shop, and then to Tucson, looking for work. In 1972 he was mugged outside a convenience store after buying cigarettes. The assailants hit him with a two-by-four and broke his jaw in 10 places.

Then he finally started to take control of his life. In 1974 he moved to Phoenix and quit drinking. Six years later he put together every cent he had and bought the bike shop from its owner. He’s run the store ever since, moving it several times, eventually settling into its current location on the northern edge of the Phoenix metropolitan area, adjacent to the New River Mountains. He met Linda at the bike shop. She stood him up on their first date but showed up the second time he asked her out. They’ve been married for 25 years. Linda says they’ve been talking privately about “Jeffrey” and replaying Ted’s youthful mistakes for years.

Ted has no other children; Linda has four sons from a previous marriage. All are close with their stepfather, especially the youngest, Darin Fala, who spent the most time with him growing up. But Ted never told them that he had another child. He says he was sure he would never see or hear anything about his son again, so what was the point?

Ted is 69 now and has heart problems, emphysema, and an aversion to the idea of retirement. “I don’t want to sit at home and rot in front of the television,” he says. He’s friendly and, his wife says, deeply compassionate. The store is less than 30 miles from four Amazon fulfillment centers, but if he ever saw Bezos on television or read an article about Amazon, he didn’t make the connection. “I didn’t know where he was, if he had a good job or not, or if he was alive or dead,” he says. The face of his child, frozen in infancy, has been stuck in his mind for nearly half a century.

He says he always wanted to reconnect with Jeffrey—whatever his occupation or station—and seems ashamed that he agreed to stay out of his life all those years ago. “I wasn’t a good father or a husband,” he says. “It was really all my fault. I don’t blame Jackie at all.”

When I left Ted and his wife after dinner, they were still in shock and decided that they weren’t going to tell Linda’s sons. The story seemed too far-fetched. But a few months later, in early 2013, I got a phone call from Fala, a senior project manager at Honeywell who also lives in Phoenix. Ted, Fala said, had called a family meeting the previous Saturday afternoon. “I bet he’s going to tell us he has a son or daughter out there,” Fala’s wife had guessed correctly.

The gathering was wrenching. “My wife calls me unemotional because she has never seen me cry,” Fala says. “Ted is the same way. Saturday was the most emotion I’ve ever seen out of him, as far as sadness and regret. It was overwhelming.” Ted decided he wanted to reach out to the Bezos family and reestablish contact and asked Fala to help him craft letters to Bezos and Jackie.

Curious about Bezos, Fala had watched online clips of the Amazon CEO being interviewed, including one from The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. He was startled to hear Bezos’s laugh. He’d heard it before. He grew up listening to it. “He has Ted’s laugh!” Fala said in amazement. “It’s almost exact.”

Excerpted from the book THE EVERYTHING STORE: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon, by Brad Stone. Copyright © 2013 by Brad Stone. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company; all rights reserved.