This Man Moved to a Desert Island to Disappear. Here’s What Happened.

And when Dave swung the dinghy wide around the cape, his customer at last caught sight of the island, a shark’s tooth of sand and grass jutting from a small mountain of impenetrable bush. Heaven! Dave said to himself.

Heavy seas shouldered the tin boat sideways. Up front, mate! Dave shouted over the bee-loud motor. His customer clambered forward and sat himself backward on the bow, twisting at the waist to keep his eyes on the islet. The evening sky behind it was striped orange to purple.

The customer was thinking about how a guy can’t get himself shipwrecked anymore. Can’t one day discover that his storm-tossed ass has been beached upon a refuge, where he’s free to wile away life, alone with the Alone. It’s impossible now. All the deserted but potentially habitable islands are privately owned, or secret naval bases, or satellite tracking stations. Among other reasons.

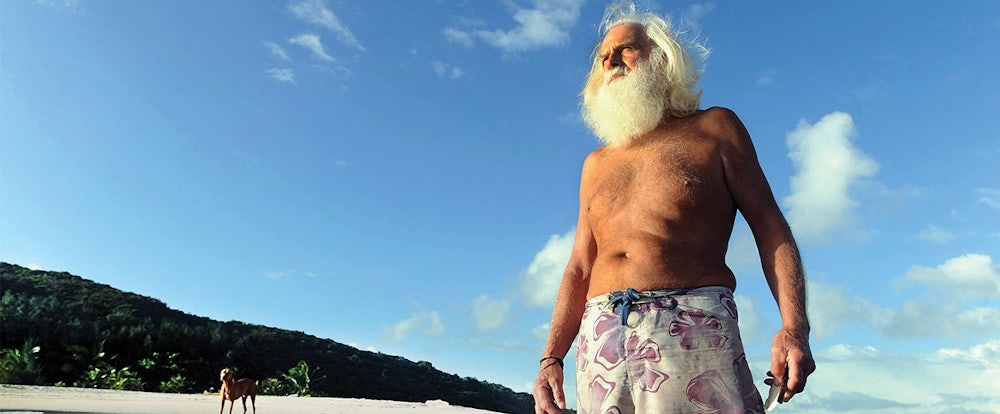

Head on a swivel! Crocs! Dave sang out, his hair a white pennant behind him. Soon to be 70, Dave Glasheen was the smooth sienna of well-oiled and -kept things. He had been living on this outlying island for more than 15 years. We wouldn’t want to swim this at night, no we wouldn’t, he said. The water leaking into the bow rose above his customer’s ankles.

Hours earlier, Dave had picked him up from a World War II–era airstrip many miles distant in the mainland’s thick jungle. This intra- Australian airfare, as well as all sea transport, had been included in the $3,100 Dave charged for his two-week desert-island experience. The customer had wired the money directly into Dave’s bank account, as instructed. Also as instructed, he’d brought salamis, two loaves of good bread, coffee, and little else.

This was like a vacation but not. The impulse was the same, maybe. Long had the customer been shopping around for a space that was remote from the world. A spot where, he hoped, everything had been got rid of except for whatever couldn’t be lived without. What the smart set’s always wanted from their getaways.

The customer had inquired after fire towers and bathyspheres, deep caves and sensory-deprivation chambers. Idaho. The Arctic. He even looked into elective lobotomies and self-trepanation, just to see. Then—of course. The desert island came to him one winter Saturday. He had been in the bathtub, apocalyptically hung over. He was paddling warm water against his face and wondering, Just what the fuck is it I’m doing here?

The question was not new. It was what his mind reset to whenever he stilled himself, stopped diverting. For instance, he would close the browser on other people’s Twitter feeds and Instagrams (he was dependent on the Internet), finally put down the book, or, yes, wake up cottonmouthed in a spinning chamber of shame—and then it would begin to materialize: WTF, man? The question wavered in his mind’s eye before tightening into painful clarity, as vision tends to do after hard blows to the head.

The truth was that most things for him had turned into giant, squawking question marks. He was living far from home in an unfashionable part of New York City, uninsured and friendless (but for the roaches). He was a relatively young man, yet even a young man’s bliss had not been his. He’d loved little but had his fill of a hell of a lot. Had indulged himself, in fact, to where he made himself sick. Now he hid from the everyday melee of competing agents and material forces whenever he wasn’t scheduled to work. Should he have to take the subway somewhere, he found himself blinking back tears. What attempts he made at meeting new people were pre-written and floated into online ether, like bottled messages. He almost wished he’d knocked somebody up.

Instead, he decided to venture to a desert island off the edge of northeastern Australia. It was at least the first step, he figured. If a boat is foundering, you dry-dock it for repairs. Likewise, if you suspect your heart has a hole in it—take yourself out of the world.

While Dave anchored his dinghy in the wave wash, the customer waded ashore, where he was immediately leapt upon by two dogs, Quasimodo and Locky. Quassi was caramel-colored and hulking, part dingo but mostly pitbull. Down his trunkish right foreleg zagged a scar like lightning along an elm—at night, Quassi guarded the island from saltwater crocodiles. Locky was a spry dun mutt, three months new to the place. He had belonged to Dave’s youngest daughter, but he wound up here after she killed herself.

Clouds had gathered, and all four walked the path to Dave’s shanty manor as hot rain began to fall. His place was just as the customer had imagined: tentatively walled, cantilevered under scabby sheet metal, and cozy with things scavenged. There were glass jars of all hues; rough furniture and rusted pots; canned goods, batteries, and salt-curled paperbacks; skeletons and snakeskins in overhanging netting; buckets under every leak; and blades, nippers, pliers, tweezers, scrapers, wrenches, wedges—too many tools to name. The lot of it reminded the customer of how a non-native speaker will hoard nouns while trying to recall the verb that animates them.

He had dreamed of such a place since childhood, when he devoured any and all books about a man improvising survival from the limited resources at hand: Robinson Crusoe, The Swiss Family Robinson, The Cay, Lord of the Flies, The Mysterious Island, Island of the Blue Dolphins, Hatchet. The Boxcar Children, even. He’d take them to the end of his street, where he had cleared his own hutch in a dark thicket of needle palms. When things went on at home that he didn’t want to be around, he crawled into this sanctuary and read, the wind fanning him with fronds.

Dave’s own clean-swept main area included a gas-powered freezer, an antenna for solar-powered phone and Internet, and an L-shaped desk, at the front of which sat an eyeless woman, unpolitely, her sundress canopied by her knees. My girlfriend, Miranda, Dave said, winking, patting the mannequin’s red hair. He showed off the adjoining patio, which sheltered a full-sized mattress looking out on the sea. He made it abundantly clear that, as near a man could find himself to self-sufficiency, to a world of his own making—here he was.

This thrilled his customer. This was what he came for. He felt in his bones that there was such a thing as Real Life; it was just—not only could he not get to its entrance, he couldn’t even see it, on account of the ocean of assholes thronging the door.

Such is why he didn’t think twice when Dave offered him several bottles of unopened homebrewed beer. He accepted them and joined his host at a driftwood table in the outdoor kitchen, intent on what he had to tell him.

Dave first set foot on the island in November 1993, having been wrecked financially six years earlier by the Australian securities crash. A marketer by trade, he’d tried to dabble in mineral exploration in Papua New Guinea. He lost all of his wealth, about $10 million, when his private venture went tits up. He thought the episode absurd—on paper he’s worth big bickies, then suddenly he’s not. But getting whacked was also the best thing that ever happened to him. A great release, it was.

He’d been a corporate bloke. He’d consulted on marketing strategies for British Tobacco, for the sport of cricket and the drink of milk. He’d been in the ice-cream game; he sold Drumsticks to Australia but failed to get TCBY into Asia. He foresaw the bottled-water craze and helped reinvent the juice box. Packaging was a very real concern for him.

Until his house was foreclosed upon, he’d lived in the most exclusive beachside neighborhood in Sydney. He’d owned two yachts, Black Erik and Erik the Red, the latter the namesake of his newly late daughter, poor ginger-headed Erika. He adored everything about skiing, especially the exclusive lodges at his favorite American slopes. (He expected to need his skis again one day soon and so kept them on the island.) He came to despise banks, big financial institutions—any of the parties he deemed responsible for making him feel right miniscule and tossed about for the first time. Wasn’t his fault the market crashed, he knew. Prior to the money poofing, he and his family had never rented a thing in their lives.

Naturally, the crash led to them having some pretty heavy ding-dongs, but Dave and his wife never formally divorced. Rather, he took up with a new woman, a white Zimbabwean named Denise. Dave talked her into changing her name to Denika—she ran a small business that sold jerky made from African game, and Dave explained to her that no one wanted to buy Denise’s African jerky. After that, he helped her manage a spa—managed the bloody thing himself—until one day she decided she wanted to get away. An island, she told him in bed, in a fit of post-coital quixotism. Our own. So, Dave called up a friend in real estate and said, I got this new bird, and I need an island.

The asking price for Restoration Island was $1.2 million. Unable to buy it outright, Dave and two partners subleased the habitable third of the island from a company that owned its rights until 2039. The agreement was contingent upon Dave and his partners developing an eco-resort worth at least $200,000, and doing so within five years. They got the requisite permits, they drew up plans for a boutique hotel. Then the KuukuYa’u people of nearby Lockhart River, rights-holders of the other two-thirds of the island, launched a title claim against them.

Though nothing came of the aboriginals’ claim, Dave learned that he couldn’t just waltz into blackfella country and have the run of the place. The KuukuYa’u hated him, fiercely, but still he moved onto Restoration and began readying it for development. Once he’d gotten set up, Denika visited for a rip-roaring couple of weeks. Certainly no family planning going on then! They conceived a son, Kye, who would spend six of his earliest months on the island. Talk about a Garden of Eden. It was a fantastic time. But Denika quickly tired of island life. Couldn’t hack it, if Dave was being perfectly honest. It got rather nasty. She demanded Dave drive her off the island but never asked him to join her. She and Kye just piked out of his world.

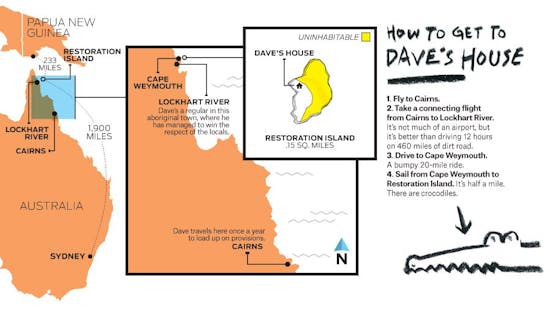

Alone thereafter, Dave’s days turned into weeks into years into decades. Occasionally, he left the island to visit Lockhart River; once a year, he went to buy supplies in faraway Cairns. Development never progressed, and the KuukuYa’u came to accept the presence of this strange white man.

The lease-holding company wanted him gone, however; they had buyers lined up but couldn’t sell their third until Restoration was uninhabited. The police wouldn’t intervene because Dave’s breach of contract was a civil matter. The resultant litigation went all the way to the Supreme Court of Queensland, where Dave, virtually penniless, represented himself. He spun a one-day hearing into six last year by presenting strange and grammatically incorrect evidence to a justice who ultimately ruled that he had “wrongly deprived the plaintiff of its asset for over a decade” while having “enjoyed its benefits.”

Dave could be put off the island with five minutes’ notice. He was at the enforced end of his marooning.

I need a white knight to kick in, you see, he told his customer as they sat under an LED lantern. Just a little seed money. Five hundred thousand. What’s that, relatively? Bugger-all. A very small amount of help, so I can buy out the majority shareholder.

Dave got up and put a pot of fresh crabs on the boil. The customer had known he was in some legal trouble, but to hear that the man who had finally found a place worth mooring after floating in limitless possibility—to hear that he was getting evicted—this disheartened him to no end. Where did a guy go if mooks in suits could reach you here?

After dinner, Dave escorted his customer a few hundred yards into the blackness, to a vaulted fiberglass hut. Inside was an undulating tile floor, two rusted bed frames topped with foam rubber, and a plastic toilet that flushed rainwater. Green lizards scampered along all surfaces, scooping mouthfuls of translucent ants as if playing jacks with their tongues. The structure was wide open at its front; from the outside, it resembled nothing so much as a shell abandoned by a giant hermit crab.

Got nothing poisonous, mate, don’t worry, Dave lied, at this time choosing not to mention his first dog, Kato, whom he found dead from a spider bite one morning at the foot of his mattress.

Dave did warn about Boxhead, however, a crocodile the size of a Buick Skylark that haunted the island. He warned that Boxhead had been stabbed once by a KuukuYa’u hunter and so hated mankind with the fury of a thousand suns. Then he said, G’night!

The wind had picked up by several dozen knots, occasionally lashing rain. It seized trees with ecstatic fury and lifted boards away from their nails, honkingly. The customer sought out Quassi and insisted he join him in the twin bed. His heart fluttered so fast that, like a propeller up to speed, it seemed to be going in two directions at once.

Dawn broke, and the customer reached for his glasses, which were gone. He bungled out onto what appeared to be a large clearing sandwiched between beach and mountainous jungle. It was covered in itchy grass and punctuated with cocos palms.

Restoration Island is a speck, a seventh of a square mile sitting only a few hundred meters offshore of the Cape York Peninsula. But the island is far removed, closer to Papua New Guinea than it is to any Australian city.

It got its name from William Bligh, the commanding lieutenant of the HMS Bounty. In 1789, Bligh’s crew mutinied after he refused to grant them a return to Tahiti, to the idyllic life (and easy natives) they imagined to be waiting for them there. The mutineers set him adrift in an open boat with a handful of loyal men. Left for dead, Bligh nonetheless managed to navigate to this island, where he and his crew scrounged food and recuperation. “Restoration Island,” they called it. They found a couple of huts, but no people.

The customer made for the northern tip of its habitable third, where the clearing, beach, and jungle met. Immediately, he tripped over something. He picked himself up and bent near the impediment and realized with a start that it was a goddamned gravestone, 40 years old and belonging to no one Dave knew. “The Sea is so vast and my ship is so small,” it read. The customer found his glasses nearby, partially eaten, in a roped-off square of scrubgrass that was, he’d learn, an aboriginal mass grave. Such had been Restoration’s local raison: The KuukuYa’u and passing sailors considered it a dump.

Now the customer could see that the island was littered with detritus. Lengths of rope, chunks of rotted wood, cashed canisters of natural gas, dead engines and fridges. He kicked aside the rinds of the salamis he brought—eaten by something in the night—as he walked through the shadow of a derelict sailboat keeled to port. Altogether, there were a dozen boats and skiffs abandoned above the tideline. Out past the breakers: a couple scuttled trawlers, now artificial reefs. It took the customer a moment to realize what it was that was off—no seagulls.

A decade ago, this island was kempt, civilized. The grass was mown and the buildings had doors. But now it abided nothing man-made. This disrepair embarrassed Dave. It made it seem as though he, too, was deteriorating. Past retirement age he might be, but he was just starting his life. He saw it all so much clearer now.

The tiki bar on the south shore, for instance. Now it had crumbled into the surf. But in 2003, he had used that tiki bar to entertain Fred Turner. Fred Turner, the McDonald’s chairman. In the midst of a fishing trip, Fred flew in on a helicopter to see the island and have a beer—and he had such a lovely time that he came back to camp on Resto with his executives and their families. Fred sat Dave at his right hand during dinners; once, he asked him to give a speech. Fred’s a hero, Dave made sure to mention in his address. Fred’s the college dropout who put the Golden Arches in 118 countries, the visionary who thought up the Chicken McNugget and the Drive-Thru and the whole standardized dining experience.

Oh, Dave hated the product, dearly. But no great man was more forward thinking than Fred. He got his millions, and then what did he do? He founded the Ronald McDonald House charity. Dave admired Fred’s class of corporate don best of all, the altruistic blokes who make it their business to help even after they’ve gathered their brass. He bet most of them were good people. How else could they have become so successful?

He explained this to his customer as they breakfasted on Cheerios and kiwis. Then Dave took him on a tour of the bush. Do you know the Google guys? he asked as they entered the jungle behind the clearing. What kind of blokes do you reckon they are?

They stopped in Dave’s garden, which stank of wild rosemary. Quassi and Locky rollicked through a sinkhole where yams, gooseberries, and bananas once grew. I hear their cafeteria gives them the healthy food for free, but you have to pay for the burgers, he said. This is the new wave of people, the I.T. blokes. They recognize that we should be better than we are.

Dave did not cultivate this garden. Normally, about a dozen backpackers would arrive throughout the year as part of the Willing Workers on Organic Farms WWOOF program. They’d care for the vegetables, landscape the island, repair Dave’s buildings, cook his meals—all in exchange for room and board on Resto. A fair trade, Dave thought, his only rule being: no camping on the beach, because of Boxhead. Some stayed a week; others, more than a year. Dave fell in love with practically every female WWOOFer who shot through. Some of those birds were bloody mature! They’d go around topless, they’d gussy up for dinner. But none had come in the last six months.

He led his customer farther up the sloping interior. He scrambled over fallen trees, naked except for board shorts, his wild white hair and cloudy beard jouncing with the effort. You can massage your internal organs through your feet, Dave advised. Tremendously important. His was a vigorous physicality, the kind often found in sinewy men of a certain age and outlook.

The out-of-doors he had learned from his father. Before sending him off to elite boarding schools, Dave’s old man was always taking him camping, fishing, even though he had been an esteemed attorney with his own busy firm in Sydney. Dave cherished the stories he heard family friends tell about how his father steered clients away from the courts, tried to get them to settle things bloke to bloke. Saved them a load of codswallop, he did.

He’d been this big bloody Irishman, his old man. A stereotypical one of theirs, you might say—touchy paterfamilias who was keen on things like driving the family to Sunday Mass while full as a boot. Dave took up the practice himself when in his teens; the whole clan’d have a laugh when he hiccupped while breaking a pound note in the collection plate.

He hadn’t been able to share those kinds of moments with his own son. You know, my Kye, he’s in his Jesus phase now, Dave said, pulling aside creeping vines. He was an OK bloke, that Jesus. Also a healer. A teen now, Kye rarely visits the island. But he’ll be back in his twenties, Dave thought. When he wants to bring out his own sheila.

Otherwise, Dave would never force the island on him. That’d push Kye away, just as his father had pushed him away from law school. Lately, Dave had begun to see just how profoundly disappointing that must’ve been for his dad, to have neither Dave nor his rellies take up the firm. It was like him here. If your children don’t come to your island, you start to wonder: What’s this for, then? His eldest, Sam, turned down his offer to have her wedding out here. She had never even come for a lob. If Kye said no, well, he reckoned he’d just have to find someone outside the company, as it were.

Erika wasn’t an option, of course, which was a shame because she was the one who visited most. Dave bloody fucking missed her. He figured that she killed herself because she had all these complications in her life. It right pissed him off. First of all, she was a gay lady. And trying to live as a gay lady even today in this society ain’t no picture painting. Second, she could drink too much. Third, she had some psychological problems, the kind you need lithium for and never used to hear about.

Dave blamed the culture. We’ve been mollycoddled; bit by bit, we’ve become marshmallows. But he also blamed himself. At least a little. Because of the separation and all that.

I’m from the wrong country, mate, Dave said, looking over his shoulder as his customer minced over a crevice. Australians don’t take risks like Americans. We’re all a bunch of bloody soft cocks. The average ones whinge and moan. Scared of their potential, I reckon.

After another half hour of tramping, they emerged onto a promontory. Dave jogged in place atop a sharp rock, the water far below him the bluish-slate of fancy cats. This island’s healed me, he said. And I can see how it could help others in a big sense. A salesman at heart, Dave rarely spoke without making and sustaining eye contact. His own were a shallow aqua, and they seemed almost to shimmer with refracted light whenever he talked business. I don’t know what it is, he said. I don’t pretend to understand it. But I feel energy here.

He’d felt it the moment he walked ashore. It was as though he’d been lost in the bush and finally heard his Cooee! call. This was good fortune. This was the genuine article. None of that other dribbleshit, the God bothering and the money chasing. Here, he had recovered his lost unity, his wholeness and harmony. Why couldn’t the power of this place be used to restore others?

Our most enduring love story, if we go by the numbers, is man + island. We in the West adore us a maroon’s tale, Robinson Crusoe being of course the urtext. Since its publication in 1719, Daniel Defoe’s novel about an enterprising castaway and his courtship of solitude has produced about 200 English and 600 foreign-language editions. To say nothing of the adaptations, imitations, and homages it continues to inspire.

Crusoe himself was based on the true-life account of a Scottish sailor, yes. Maybe. No one’s sure to what extent. Anyhow, over the centuries, Crusoe’s place in our cultural consciousness has continued to shift. We’ve sort of willed ourselves into forgetting that he’s a character rendered whole by an author. He has come now to exist in a kind of limbo: We don’t believe he was a historical person—but we don’t believe he’s entirely fictional, either.

One thing he was, though, was our first realistic portrayal of the radical individualist. In Defoe’s story, Crusoe gets shipwrecked on a desert island with only a pocketknife and a little tobacco in his pipe. Things look grim until he pulls himself together and works to make a heaven of this hell. Via rational thought and elbow grease, Crusoe discovers that his unfathomable depths contain: an architect, an astronomer, a baker, a carpenter, a potter, a farmer, a tailor, and an umbrella-maker. He builds a fenced-in redoubt, plants crops and a privacy hedge. He glazes pots, bakes bread, stitches clothes from animal skins. He wrights a ship with a sail and a parasol. And, most incessantly, he accounts for and makes use of every single thing he comes across, people included.

Robinson Crusoe values people not as human beings, but as objects that might be of some utility to him now or down the line. For example, the Moorish boy who helps him escape from a pre-island bit of slavery? Crusoe turns around and sells him into slavery. He comes to regret the sale, but only because it would’ve been nice to have an extra set of hands around. (“Now I wished for my boy Xury, and the long-boat with shoulder-of-mutton sail …”) The first word he teaches to Friday, the native companion he recruits? “Master.”

Crusoe is free and accountable to no one, preferring his hard new liberty to the easy yoke of society. He claims to find God on the island—but, just in case, he takes care to learn how to wrest his own good from himself. “I was lord of the whole manor,” he says, “or if I pleased I could call my self king or emperor over the whole country which I had possession of. There were no rivals; I had no competitor.” Depending on your mien, that might sound like paradise. Or, on the other hand, the wet-dream somniloquy of a tyrant or monopolist.

Regardless, Robinson Crusoe remains one of our most influential dead white men. For better and for worse. As James Joyce said of him, “The whole Anglo-Saxon spirit is in Crusoe: the manly independence; the unconscious cruelty; the persistence; the slow yet efficient intelligence; the sexual apathy; the practical, well-balanced religiousness; the calculating taciturnity.” He’s who’s behind the Boy Scouts, libertarianism, and 300 years’ worth of solitary, self-reliant heroes. He was wise to our condition, this isolato, and the story he invented for himself out of his freedom still reads like a survival guide, a crash course in modern existence.

My dream is to create a healing center here, Dave said to his customer as he turned the dinghy up a muddy creek. For corporate people. The time-poor; not the mob. He angled the motor out of the shallow water, and the two of them slid underneath an arch of mangroves threaded together like prayerful hands. I think the mob’s just looking for a quick fix. Do you think those people are equipped to heal themselves?

A wince rippled across the customer’s face. He threw out a line weighted with wire leader and a realistic six-inch lure, holding it loosely in his right hand while it trailed behind the boat. Dave went on: It all starts with the individual, you see. People need to restore themselves. But they need to have the infrastructure to do so. That’s where I come in. I’ll have ’em come here, and then I’ll give ’em an umbrella and an esky of champagne before buggering off. A club atmosphere, hey? Have the Google blokes visit. He was thinking of charging what he’d heard was the going rate for these sorts of things, four thousand—Australian—per day.

Dave made little slashing gestures over the jungle to show his customer where he intended to level trails for the elderly and less-abled. This’ll be private, word-of-mouth, he said. Right now I’m building a network of therapists and wellness birds who’ll refer patients. A nice way to cop a flow. Here, a funicular would run. There, a meditation pavilion. Up higher: wind turbines. Dave pointed out six treehouse units that only he could see. It’ll be on a ninety-nine-year sublease, with some of the KuukuYa’u as employees, he said. That’s what the guests’ll want, anyway. After ninety-nine years, they should be ready to take over.

The wind blew in regular glugs, as if somewhere someone had unbunged the day. I just need five hundred thousand dollars to deal myself back into the game. Shit, I used to pump that in a fucking day, mate.

The customer sat there nodding and emoting, and puppeteering the fishing line so that it kept clear of mangrove roots. But really, he was considering how, the week before he left for Resto, he went five consecutive days without talking to another human being. A few drops of rain began to pop against the tin hull, and he wondered if he would ever find a companion as companionable as his detachment.

What we need first, though, is girls, Dave continued, punting the dinghy out of the creek and into deep water. Some nice sheilas would be good. Some nice female partners who aren’t bitches. Though I figure that’s hard to find. He tugged the engine’s pullcord.

Dave had been thinking a lot about Oriental birds. They’d probably do right-o on the island. I’m so far out of the loop, mate, he shouted. I need to go to love school! He’d tried online dating. Five years ago, a female WWOOFer set up a profile for him. There was a tremendous response—but from depressives and alcoholics. He tried all those damn websites.

Something hit the line, hard, yanking the customer’s right arm behind him. Then it went slack again.

I got this TV bird coming, Dave said. She’s rather prominent, I reckon. Knows a lot about the wellness industry. And she just split up from her hubby! She has kids, which I’m not certain how that will work out.

He circled the reefs that had grown around the scuttled trawlers. No, he said, there’s nothing wrong with a bird coming and trying before she buys. Have a nice seafood dinner. Who would you invite to dinner if you could? I would take the Dalai Lama and Obama, for the peace, love, and understanding, and then I’d have Osama, for the opposite. Not including the bird, obviously.

They fished for another hour, unaware that they were towing empty monofilament, the wire leader and the whole lure having been bit off a ways back.

All desert-island stories are in some sense about waiting. Waiting for rescue; waiting for madness; waiting day in, day out for time to be transcended. By this point in his stay, the customer was waiting for Dave to shut the fuck up.

Dave’s babbling was impersonal and often senseless, like nature. It was always going and just loud enough to hear, like an Orwellian radio, or self-consciousness. Tense-wise, it was never simply present but always progressive. The customer’s eyes were going a little cross from so much sustained contact. And all that polite smiling and contorted pseudo-concern—his face was exhausted. Sometimes, he brought an empty coffee cup to his lips and pretended to tip back the dregs, just to give himself a moment’s relief.

While oystering, while gathering palm fronds, stacking coconuts, spinning fishing lines—while siphoning gas—Dave kept on keeping on. He’d soliloquize about Australia’s 10 percent goods-and-services tax. The relative value of Canadian economic geologists. Laser nuclear power. Corn subsidies. The prices of: Kenyan cattle, land in California’s Central Valley, the water necessary to grow rice. He speculated on the fortunes to be made in table compressors, stone cutting, olive oil, ski lodges based out of ancient castles (of which there were many for sale, don’t worry), opal.

At first, his customer had tried to redirect the monologic torrent. But Dave was inexorable; he just steady beat on like the sun. His ceaseless reasoning debilitated. It melted whatever steering queries or transitional declaratives the customer had in mind. Over time, he became stupefied, able only to answer Yeah or Right, the conversational equivalent of rubbing away eye floaters.

One afternoon, he thought to get away by taking a rusty pitching wedge and sneaking off to a patch of fallen plums at the edge of the clearing. Violet pulp splacked his face and bare chest each time he teed off; the rain washed him clean. After a dozen cathartic strokes, he looked up, and there was Dave, his logorrheic caddy, yippy-yapping about: trickle-down economics and the importance of job creators (There being nothing wrong with making money!). Carlos Slim and the state of the Australian telecom industry (A bloody fucking monopoly!). How one gets only two or three opportunities in one’s life to make serious money (The idea being a hop-on, hop-off bus, like Ken Kesey’s, but for backpackers in America).

The customer waited less and less hopefully for a connection to develop between himself and the man. He was beginning to feel stronger swirls of dread, as though he had skipped forward along one possible branch of a personalized Choose Your Own Adventure and needed to work out how he got there. So, he went on the offensive. He asked Dave about the first time he confronted the deep water of real, prolonged silence. He wondered whether what happened inside Dave’s headspace was anything like the unpacking of luggage. He wanted to know: In renouncing the world, did Dave discover a pure and gentle sympathy with all other men? Did the island lead him to understand that true solitude is not mere separateness, but rather a discipline that tends only toward uni—

Right, no. You don’t come here to reconnect with no hoo-doo. I want to point you in the direction of fixing yourself. Get you to look inside, get down to the nitty-gritty. With both hands, Dave pantomimed an hourglass figure around his customer. You know, I could never understand song lyrics until I came out here? I like myself way more now than I ever did.

Dave had wanted to come ashore because a package was waiting for him at the inn. Getting to it took several hours, as first he and his customer had to borrow a truck from a bush family, and then they had to fix the tire that blew out on the way there. When Dave had finally retrieved the padded mailer, he pulled it open slowly, with his fingertips. Inside were discs containing an hour-long television special the BBC had filmed about him some months back. Dave was going into Lockhart River to give copies to everyone he knew.

About 800 KuukuYa’u lived there, though that number fluctuated seasonally. They made up one of the most isolated and economically disadvantaged communities in Australia. Lockhart River is a twelve-hour dirt-road drive from Cairns, the nearest city, and a four-hour drive from Weipa, the nearest town. The unemployment rate there was around 20 percent, three times the national average. The community was almost entirely dependent upon government aid. They had gone so far as to ban alcohol six years earlier, an emergency measure, because their life expectancy had fallen to an age two decades younger than that of white Australia.

It took a decade for them to trust me, to stop calling me “white cunt,” Dave said, pulling the loaner truck onto the gray beach outside of town. The sky there was like a lint trap, the sea rough and opaque. Now I see myself as an agent of the KuukuYa’u.

He and his customer tore into prepackaged meat pies purchased from Lockhart’s exorbitant general store. The pies and occasionally some fresh veg were all that Dave allowed himself there; his real supplies—canned goods, flour, cooking oil, natural gas—he bought in Cairns during his annual trip. He had to have that tucker shipped to the island via barge, a great drain on the $10,000 pension he made do on.

We’ve got to get these government blokes out of here, Dave said, his mustache baubled with gravy. There’s ten saviors for every one they’re trying to save. Lockhart River’ll save themselves when they’re ready.

Erika had put in five years working for the government in Lockhart, and what had that got her? Government was always tossing this money about, building new facilities. But the people? Erika had been a literacy aide, and a volunteer culinary instructor, and still they made her live in a back room at the employment bureau. She didn’t even have her own fucking bathroom! A sheila without a bathroom. What a bloody waste of potential. Dave wouldn’t have treated his employees that way 30 damn years ago.

All these yobbos, but did you know government don’t have a full-time drug and alcohol counselor here in Lockhart? Dave asked. He was going to use the money from Erika’s estate to fund one.

He put the loaner into gear and showed off Lockhart’s sole restaurant and then its arts center, where two English bird-watchers recognized him from the BBC program. The town proper reminded the customer of the depressed agricultural villages ringing Lake Okeechobee, only much direr: There were brightly colored shotgun homes, hit-or-miss lawn care, a lot of stripped-down cars, and too many feral dogs fighting in the street over bones that were three feet long.

They left the truck and walked into an open-air pavilion behind the church, where a well-attended shire council meeting was just concluding. Adults milled; kids and dogs schooled like fish. Dave had working knowledge of everyone present and a rapport with most. A few locals answered his personal questions cheerlessly; a few others tolerated him like pupils do a hammy administrator. Still more begged for homebrew. But many were plain happy to see him, calling him “old fella,” a sign of respect. They were so accustomed to white men coming and going, implementing things and then flying away, that Dave’s continued presence proved him to be true blue, dinky di.

Dave grabbed a couple complimentary plates of sausages and buttered bread and took a seat at the long councilmen’s table next to his good friend Paul Piva, a genial South Sea Islander fit to bursting with muscle.

How we met was Paul’d come to the island to sneak a beer and have some fishing, Dave said. They hit it off immediately, owing to Paul’s latent entrepreneurial instincts. He followed Dave’s advice, and now he ran a small business renting salvaged cars to the myriad government employees who flew into Lockhart every week.

I tried to get him to run for mayor once, Dave said. Now I’m trying to teach him whitefella law. I don’t want any whitefella thinking he can come in here and take advantage of Paul just because he’s a blackfella.

Years ago, Dave had made sure Paul was there on the island the one time its leaseholders tried and failed to evict him in person. The fucking wankers, Paul said of them, flashing a wide smile of kerneled teeth. The fucking ding-a-lings. Damn right Paul would dong anyone who tried to get rid of his friend. But he didn’t think he’d need to; he was convinced Dave would be coming up with the money to buy back his share. The climate’s no bloody good, Paul said, so alls Dave has to do is hand them $500,000, and they’ll fucking jump.

That fucking island, Paul continued, rolling up the hem of his polo shirt to rub the oak dome of his stomach. Fuck, it’s a goldmine for us! The jobs! If I thought Dave’s plan was bullshit, mate, I’d tell you straight up.

After the meeting, having distributed copies of the BBC documentary around Lockhart, Dave and his customer snuck into a KuukuYa’u ceremony put on for white benefactors and executive out-of-towners. Along the dreary beachfront, children danced in grass skirts while singing a sad hymn about the devil disguising himself as a crocodile and stealing a baby in the night.

With his tongue, Dave joggled the edge of his loose left canine while eyeing the business-types. No doubt it was terrible how the KuukuYa’u got addicted to things, he explained. Grog, government money. Smoke-o, even. They had been a nomadic people, you see, not accustomed to surplus. More than your regular yob, the KuukuYa’u were going to eat or drink or take whatever was on hand until it—or they—were gone.

But if there was one thing that had carried over from Dave’s days on the mainland, it was finding a niche and filling it first. Business abhors a vacuum, after all. He leaned in to his customer, whispering, Don’t you reckon these blokes would love to have a shout and a session? But they can’t here in Lockhart. That ain’t civilization. It just ain’t. No, I plan on rebuilding the canteen. Have it be a club-type atmosphere, but strict. Anybody who comes in to crack the shits will be tossed. Paul’s against it. But she’ll be right, mate.

Robinson Crusoe is no longer required reading, but that’s only because it doesn’t need to be. The desert-island story has so permeated our culture that it has become its own meta-genre: the Robinsonade. There’s Cast Away and “Survivor” and “LOST,” obviously, but also Life of Pi, The Hunger Games, and any one of the 700 movies that came out this summer that had to do with what comes after Armageddon. If it touches on isolation, tabulae rasae, or close encounters of a new kind, or if it has a character commenting on society from the outside—it’s a Robinsonade. The island need only be metaphorical. It’s all about the lone protagonist ad-libbing his life.

So, no, we don’t make kids read Robinson Crusoe. Instead we’ve got them reading the domestic version, Walden.

Unlike Crusoe, Henry David Thoreau did the American thing and chose to live apart from the world. He erranded into the wilderness voluntarily, hoping there to find a purer, more deliberate way of being.

He was a huge admirer of Crusoe. There are allusions to him everywhere in Thoreau’s writing—from the notched stick Thoreau measures time by, to the umbrella he sometimes carries, to his long, addled digression in Walden on hats made out of skin. In his letters, Thoreau compared himself with Crusoe a lot, and unfavorably. Crusoe had “the callous palms of the laborer,” which were “conversant with the finer tissues of self-respect and heroism, whose touch thrills the heart.” Crusoe could philosophize and carpenter a coffin for the dudes he shot. Thoreau wanted to be a hero in that mold.

Thus did he borrow an axe, go into his pal Emerson’s backyard, and clear a space for the repurposed cabin he bought from an Irish laborer. He detailed in a journal how he dug his cellar, maintained his hearth, and struggled with weeds and poor soil in his garden. Just like his man Robinson, Thoreau kept track of himself via credentialing lists, commonsense routines, and economic pursuits. He walked in the woods and went for some swims. He labored after a conspicuous authenticity.

But he certainly was no recluse. The road from Concord to Lincoln was a field away from him. He could hear the Fitchburg Railroad when it steamed on by. Almost every day, he went into town. On weekends, the children of Concord picnicked around his pond. Sundays, his mom dropped off goodie baskets.

And after two years in the woods, Thoreau wrote a really strange book about it. Walden is many things: diary, sermon, nature travelogue, proto-boho fantasy about dropping out. But what ties it all together is the man himself. Thoreau is the book’s true subject. If Robinson Crusoe is the manual of rugged individualism, Walden then is the apotheosis of the wannabe- rugged individual.

“The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation,” Thoreau wrote at his book’s beginning. He would know—he was having a midlife crisis 125 years before the baby-boomers made it a thing. Via Walden, he became the early popularizer of that most American of notions, the one which proclaims that, to be happy, we need to be someplace other than where we are. A place more authentic, where we’ll finally be free to turn into ourselves, use our innate powers to create. Not a new Eden, mind you, but a new and better Adam.

“Let him step to the music which he hears,” Thoreau wrote, “however measured or far away.” This isn’t an advocacy for solitude; more like the warm dream of a private religion.

The customer left the red cave of his closed eyes, reluctantly. It was morning, and he had yet to sleep well. Each night, the wind played the island like a bad one-man band, and every few hours Quassi went tear-assing into the darkness, barking like mad.

He could not wait to wake up in a place that was not this place. Which was exactly how he wound up here.

Dave was seated at his desk, Miranda splayed in front of it. He was calling friends and business partners, former and potential, talking up the BBC program among other things. His customer sat apart and watched Dave work. He saw that, whether in person or on the phone, Dave’s aspect never changed. His eyes locked on, but to some middle distance, neither here nor there. He seemed unable to see but rather was projecting something, like a camera obscura.

Mate, I’m telling you, he said into the receiver, you can’t rob from the rich to pay for the poor. All that does is make more poor! … Well, the potential is in the untapped market of Chinese WWOOFers. … No, America loves to help people. But they’re not helping themselves.

Each call restarted his spiel, Dave like a human infomercial on the hour. When he got good and humming, he had the cadence and sly humor of a carnival barker-cum-revivalist. Our utter financial collapse is like the pregnant schoolgirl, he said. Eventually that baby’s gonna come! After a few hours of such inveigling, he grabbed his iPad and joined his customer at the driftwood table.

What’s my current password? Dave asked, poking at a commodities report he ordered online. You know, precious-metal market psychology has been absolutely smashed by the banks …

The customer heard a crunching noise. He looked to Quassi, who was lying at his feet. Quassi was eyeing Locky, who was sprawled a ways off. Between his paws writhed a blue and yellow songbird. He nosed it once, twice, and then bit off its broken right wing. The good left one flapped erratically, to the rhythm of the bird’s heartbeat.

… The smart corporates recognize the value of that, Dave was saying. Something about optimism and Google. I was through the looking glass here.

This time, when I came to, I made some snide comments about data mining and the NSA. I made up even more egregious privacy breaches for Google to perpetrate, just to shake Dave’s faith in corporate futurism. I was done with biding my time, with hoping—like some son at the home with his demented father—for a flicker of cognizance.

But, anyway, do you think they’d like to come here? The Google blokes? he asked, exaggeratedly flipping between financial forecasts on his iPad. Do you think they’d come to an island to get restored? Onto the table in front of my folded hands dropped two mosquitoes, flushed and coupling. Well, of course, they would have to do the restoring themselves, Dave added.

Here’s one way I often find myself passing the time in my apartment: I turn on the Home Shopping Network, I lie supine on the carpet, and I listen as people try to sell me on stuff. It’s like my every day, only a screen removed. I close my eyes and let the song and dance wash over me. I feel tickled; feel this wriggling, duodenal bliss that’s akin to having unscratched bug bites all over. The pleasure is anticipatory. I know that, when I’m good and ready, I can do here what I cannot outside—I can shut it all off.

That and a bath are my consolations. But they’re also symptomatic of a larger issue: After four hours anywhere, with anyone, I get mortified. I become obsessed with a perpetual elsewhere. If I can’t duck out—I dissociate. Not like a guy with a mental disorder. I know I’m in here. But the persona doing the shit-eating is just that, a front. A decoy. The real me is watching from without. Gauging. The me who thinks and feels and is remains elsewhere.

Of course, to my mind, this decoy’s doing a bang-up job of advertising how I wish I felt. Mr. Golem B. Kool, all revivifying smiles and conspiratorial winks. But the reality of it, I’m sure, is different. To others, I must appear as frightened, condemnatory, and doomed as a plague nurse in one of those birdy masks.

… A classic give-and-take, Dave was saying, rain plunking into overflowing jugs. I’m in a situation where I need the media to help me. It’s a fair trade: I give you a story, you give me publicity. At this point, I wouldn’t even mind a reality TV show if they brought some nice girls with them.

I will admit I hadn’t counted on Dave being such a dratted social butterfly. Alone on an island was where I figured a man would have found peace. Meaning, he’d be happy, but he’d never have a good time. That, or he’d be a crazy person anxious to brain me with a conch in the night. But Dave’s guestbook offered proof to the contrary in both cases. It was fat with the signatures of hundreds of visitors. And not just the WWOOFers or the KuukuYa’u, but French luxury yachters, recreational divers, sport fishermen—Russell freaking Crowe stopped by on his honeymoon, apparently. Almost every one of their entries reads the same, something like: “Utopia at last!” “A piece of heaven.” “NO REASON FOR THE STRESS!!” “It was the perfect remedy to life!”

Was it, though? You might not be able to be a castaway in the original sense anymore, but neither can you half-ass the experience. You don’t just buy a round-trip ticket to peace of mind and post pictures to Facebook later, another consumptive merit badge. If only.

I returned my attention to Dave. He was saying: I feel safe here on the island if it all goes down. Which I think it will. It’s that I’m off the drug of money. Some blokes think gold’s the answer, but gold . . . it’s as safe as houses. Whereas silver, old sixpences and shit—it’s a byproduct. Useful in electronics. Sometimes, you know, there’s more value in the byproduct than the product. The sheilas understand it, silver. I nodded as absently as the palms in the gale. Who runs the family budget? The sheilas. And they hide silver around the house, don’t they? I knew this one old bird who filled half a dozen forty-four-gallon drums with the stuff and buried them in the yard. I admire her immensely, I do.

Ain’t a damned thing therapeutic about this place. Womb-like it is not—far more purgatorial than that. And Dave, bless him, the more he droned on and on about the enlightened man’s need for a spot to sit still and wand a metal detector over his soul, the more certain I became that no matter where I go to find myself—be it a South Pacific hovel isle; teak-floored villa with curtains a-billow; or the stained carpet in my uptown cesshole—I’ll keep unearthing this gem: I am shipwrecked with a self I both fear for and loathe.

So. How did those guys escape Alcatraz, again?

Is it that I say nuts to the faux-biblical jargon of authenticity, with its consumerist undertow and accessorized cant of separation and lost harmony? Instead I should just try to wrap my head around the infinite extent of my relations and thank God I am like other men? Then I could allow myself to be swallowed by this seemingly commonplace epiphany, so much so that I become borderless, like a fish swimming at night?

Seriously. I’m asking. Which, Jesus, do you know how hard that is?

Is it that I’m not allowed off this rock until something has died?

Nobody’s gonna restore themselves, I told Dave. But I doubt they had it in them in the first place.

During the darkest hour before sunrise, the customer turned on his flashlight and left his bed, having yet to explore the island at night. Quassi took up after him with the weary compassion of all bedside attendants. The wind sounded like fire, like whoof, flames chasing oxygen.

Mosquitoes were landing on his bare arms and legs, but the customer waited a couple of beats before waving them off. He considered how the lifespan of a bug bite is exactly like that of a star: First they’re big, warm, and nebulous; then they collapse into hot little pinpricks. He swept his path to the beach with the beam of his flashlight.

When he reached the top of a dune leading down to the water, he heard Quassi’s growl go gnarly. The dog shot past him, running for the surf. The customer scribbled his mote of light over fizzy spume, trying frantically to locate what had spooked them both.

Two eyes shined greenly. Then they extinguished themselves. Next there came a snort, and some thing sliding sliding sliding into the breakers. At this point, I think, I began to appreciate that whatever it is I would like to find, it lies beyond or under all my attempts to find it. I said, Holy shit.

Kent Russell is a writer living in New York. His last piece for the magazine, “The Boys of Lancaster,” was about Amish baseball.