cw: Speaking of unsung heroes: http://t.co/V8N6G5lQTl

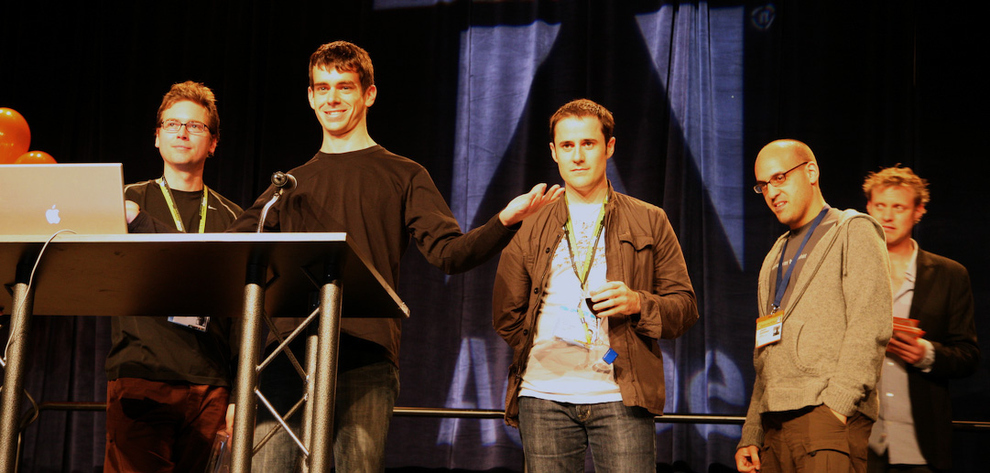

Biz Stone, Jack Dorsey, Ev Williams and Jason Goldman accept the award for “Best Blog” on behalf of Twitter at SXSW 2007. Photo by Scott Beale.

This past January, two of Twitter’s founders appeared on Charlie Rose. After stepping back from the microblogging service — it’s now valued at $10 billion, and expected to go public this year — Evan Williams and Biz Stone were at work on two new websites, called Medium and Branch, with the twin ambitions of rethinking online publishing and dialogue. And so Rose billed their appearance as a conversation about conversation.

“Is there a yin and yang here?” asked Rose. “I sit at this table and have for more than twenty years, having conversations often for an hour. And you guys pioneered the idea that you can say it all in 140 characters?”

Williams smirked. “I think we pioneered that you can say something in 140 characters.” Affected modesty aside, this is an exceptional — and true — claim. The people sitting at that table had changed the way the internet writes, shares and thinks. But they had help.

Unlike sometimes-competitor Facebook, a singularly Mark Zuckerberg production, Twitter comes from a large family. Beyond Williams and Stone, there’s the third founder, Jack Dorsey, the golden boy of Silicon Valley who mused recently on 60 Minutes about becoming New York’s mayor. There were two engineers who helped Dorsey build the prototype for Twitter in 2006, who were dismissed in short order. And after ousting Dorsey from the top job in 2008, Williams turned it over two years later to the current C.E.O., Dick Costolo.

Also absent from the table, and, largely, from Twitter’s public profile, was Jason Goldman. An office manager at Williams’ previous startup, Goldman worked his way up to run product development at Twitter. He claimed a seat on the company’s board (as did Williams and Dorsey, but not Stone), oversaw a team of 40, and remains a meaningful stakeholder. When Goldman stepped down from Twitter in 2010, after overseeing the expansive redesign that became “New Twitter” (and transformed Twitter into a fundamentally different type of company), he joined Williams and Stone in rebooting the Obvious Corporation, which had initially incubated Twitter. This time, the three are partners. Yet on the Charlie Rose segment, he was nowhere to be seen — or heard about.

“He engineered a kind of behind-the-scenes, Wizard of Oz role for himself,” Stone told me of his friend. The 36-year-old Goldman, by all counts, has intentionally maintained a low profile. When we met earlier this year, for two lengthy conversations, it was at the urging of Josh Miller, the 22-year-old C.E.O. of Branch, where Goldman serves on the board. But then it’s not as if paparazzi are beating down Goldman’s door. The fourth estate forms its cults around outsized personalities: Soon after Dorsey returned to Twitter, in 2011, Vanity Fair noticed his slim Prada suits, Rolex watch and hand-sewn iPad case; the day before Charlie Rose aired, he was photographed on a yacht near St. Barths with Brian Grazer and the model Lily Cole.

Jason Goldman may boast 1.2 million Twitter followers, but search for him on Wikipedia and all you’ll find is an article on Michael Bublé’s former saxophonist.

Last year, Jason Goldman decamped to New York. While his partners remain on the West Coast, Goldman is embedded at the Branch offices, coaching Miller and team. Branch, a sort of digital salon for the Internet set, is headquartered on an unlovely stretch of 23rd Street, beside a Public Library outpost. One day in February, I met Goldman in a spare conference room there. With a studious intensity, he looked out from behind a pair of blue titanium glasses, bearded and a little eggheaded. Someone had drawn a light bulb on the whiteboard behind him, making it look as if Goldman were continuously having a bright idea.

He was explaining the product manager’s role, and not exactly overselling it. “You’re the one that types the meeting notes, the one that is over-communicating the schedule, the one that goes and takes the meeting with the person no one else wants to meet with,” he said of his early work in the field. “You’re just doing a lot of grunt work to make things run smoother.” His first jobs were in user support, “in understanding how people use software,” he remembered. “It’s a great path into project management. You don’t have to be a designer, you don’t have to be an engineer.”

“Product,” in tech circles, is something of a catchall. “Building. Communicating. Helping. Simplifying. Collaborating. (Sometimes) Crying. Leading,” Google’s former product guru, Hunter Walk, writes. Product managers are sometimes said to oversee discrete components of a company, like feudal lords in a kingdom. But for many P.M.s, Goldman’s assessment is closer to reality. “Everybody says the project manager is the C.E.O. of their project, and I think that’s total bullshit,” says Josh Elman, a former manager at Facebook and Twitter, the latter under Goldman. “The real heart of a product manager is the guy who sits in the back of the raft with the oar.”

Goldman learned the trade behind a shop counter. Growing up, the St. Louis native lorded over his high school’s geek squad. Quiz bowl, math club, debate team: he was an officer in all of them, even running the academic club that managed the other academic clubs. “I was really focussed on being the best nerd possible,” he told me. “My job in life was to be an intellectual processing unit.” Goldman’s mother, Michelle Jones, taught in the school district, and encouraged her mini-C.P.U. by bringing home Apple computers on summer loan. “He always had leadership skills,” said Jones, “not in a bossy, dictatorial type way. Even though he set goals for himself, he also set goals for the organization.”

In high school, Goldman took a job at St. Louis’s local alternative to CompUSA. “Most of the people who worked there really just wanted free games,” remembered Jason Sutter, a friend from the store. “Goldman was much more interested in talking to people and finding the thing that would help them do whatever it was they were having trouble with.” When Windows 95 came out, Goldman ranked as the store’s top seller. Customers would come in requesting a flight simulator, and leave with $40 of extended memory. “That sounds like a complete snow job if you don’t understand,” Goldman recalled. “But if I can describe it in sufficient detail, and explain to you why this problem exists, you’ll trust me.” It’s not that he was working on commission; the shoppers needed memory to play the game.

Troubleshooting behind the counter is perfect training for a product guy, overworked and unsung. If it sounds less plush than the chief executive’s chair, that’s because it is. These days, tech founders, like Hollywood directors, are commonly hailed as visionaries — delivering, like Moses and his tablets, sweeping blueprints for the way forward. Goldman worked under three Twitter leaders, but fashioned a consistent role for himself. At strategy sessions, he said, the C.E.O. would articulate a broad but pithy vision, and sit down to applause. “I’m the guy who stands up next, and says what does that mean in terms of what we’re building over the next six months,” he said. That’s the gritty work of fielding questions, farming out assignments and reconciling disagreements. “Your presentation doesn’t sound as good. Your presentation doesn’t have grand, inspiring goals,” Goldman went on. “You’re the guy who stands up and says, next week we’re going to fix a bunch of bugs. You’re the person that’s managing the fallout from the grand vision.”

Product managers, in this view, are agnostic to the idea, so long as they’re assiduous in its completion. They’re almost the inverse of how we conceptualize the ideal C.E.O. “He wasn’t the idea guy, as maybe some product people are,” Williams told me of Goldman. “He’s not necessarily defining what we need to do, he’s just making sure it got done. I don’t know that it’s a typical relationship, but it’s probably not super uncommon,” Williams added. In a boardroom crowded with idea guys, where “the very notion of what the product was would evolve,” said Goldman, “owning the whatness of the product” might sound humdrum, but it was by most accounts critical.

When Facebook I.P.O.’d last year, Mark Zuckerberg became the Fortune 1000’s youngest chief executive. Tom Wolfe anointed Zuck the “John Jacob Astor, the Andrew Carnegie, the E.H. Harriman, the John D. Rockefeller, the Henry Ford, the Bill Gates of our century.” A standout, certainly, he’s not quite an anomaly: of the 42 technology companies that went public in 2011, eight claimed leaders under 40. To the enterprising youth, a billion dollars must have never seemed so attainable. Perhaps as a consequence, Zuckerberg’s generation is allergic to middle management, habitually browsing the App Store for the next American Dream.

Today, a high achiever like Goldman might have forsaken college for a shot at striking gold; last week, Yahoo shelled out $30 million to an app developer younger than the establishing papers of his acquirer. But when Goldman came up it was a different time; the high school valedictorian shipped off to Princeton sight-unseen. Goldman divided his time there between strange academic bedfellows: astrophysics and parliamentary debate. Used to being a head smarter than the next kid, he was for the first time challenged. Study halls could run for as long as twenty hours, and Goldman found his best chance at success was to collaborate. “It was sort of like project managing problem-set sessions,” he remembered of the marathon sessions.

Where he hit his stride was as a college debater. Among the disputatious humanities majors, Goldman was something of an odd duck. Jeremiah Gordon, a teammate, remembers a chain-smoking stargazer, a little bit standoffish, who logged long hours in the lab. “The guy you meet now is very different,” Gordon said. But at weekend tournaments up and down the Eastern seaboard, Goldman more than held his own. “I knew him in the context of a point system,” said Anna Utgoff, his debate partner, “where he was literally being ranked on whether he was the smartest guy in the room. Multiple times, people were like: that guy.” In 1998, Goldman and another partner won the award for best team of the year.

Goldman had no plans for the future, in part because “there was no professional debate circuit,” he joked. When the management consulting firm McKinsey came to campus, he sat for a rote interview. While his peers signed offers with investment banks or shipped off to law school, Goldman was “basically rejecting the credential treadmill,” he told me. Later, he came to realize that “being the most famous college debater is as virtuous as being the most famous tech entrepreneur. That pursuit of glory is very mistaken.” He was learning humility: a rare quality in chief executives, but vital in product management. Of course, the flip side was that he neglected his studies, and had to take an extension on his senior thesis. His advisor coined a “catchy title” for it — X-Ray Clusters, Baryon Fraction and the Mass-Density of the Universe — and called in a favor for her reluctant mentee at Johns Hopkins.

After one semester as a PhD candidate, Goldman dropped out and moved cross-country, where his college girlfriend was studying at Berkeley. In January of 2000, he sat in a recruitment office in San Francisco. “All this is blowing up,” the headhunter gestured out to Market Street, a commercial artery through the city’s heart. The dot-com bubble was a few months from bursting. By a stroke of luck, the job Goldman landed was with a manufacturer of risk-management software; the kind of thing in high demand during a crash. Over the next two years, Goldman learned the ins and outs of project management, writing specs, triaging bugs, servicing clients, and interfacing between the technical and executive branches. It was slow, steady and unheralded work, and it served Goldman well.

Later on, Goldman’s colleagues would salute his appreciation for the little things. “It seems like an inglorious job, but given Jason’s personality, it’s a lot of little wins he can celebrate,” said Stone. “Every time he ticks a box off, that’s another level-up in his game of life. It’s like getting an extra life in Super Mario Brothers.” Shepherding products to fruition is like working your way up to Bowser, protracted, hard-fought and without many hosannas. Stone went on, “As opposed to just empty praise, if he feels he’s accomplished things, that feeds his ego.” As Williams told me, “He doesn’t need the spotlight. He doesn’t need prestige, he just needs to help.”

Helping hands aren’t often high-fived in Silicon Valley, at least publicly. Code.org, an advocacy group for computer science education, has registered almost 10 million views on a YouTube spot featuring C.E.O.s like Zuckerberg, Dorsey and Bill Gates. The video is fitfully strange: “It’s really not unlike playing an instrument or playing a sport,” says Drew Houston, the Dropbox founder, as the Miami Heat’s Chris Bosh completes a slam dunk. Implied is a causal link between programming and paydays, and between determined coders and their apparently singlehanded creations. It’s a rare child who, watching a video like that, will set his heart on coaching from the sidelines.

Older audiences, refreshing TechCrunch or Mashable for their daily tech fix, will encounter similar narratives — founders are elevated as heroes by the people who cover them. On the day that Facebook announced its acquisition of Instagram, TechCrunch changed its logo to incorporate the faces of the two founders.

Adulatory coverage doesn’t just indulge founders, it sometimes makes them very wealthy. Nick D’Aloisio, the 17-year-old who just cashed out with Yahoo!, picked up his first investors through a story on TechCrunch. In fact, as Gawker revealed, D’Aloisio once sent Gizmodo writers over 100 frantic emails pleading for a hit (“if we don’t get featured. We’ll go bust and I’ll end up unemployed”). Despite revelations that D’Aloisio may have licensed part of the technology he sold, he’s been roundly celebrated after the sale. Not so for the less self-promotional; through Twitter’s various successes, Goldman’s contributions have been celebrated almost in secret. In 2010, a prominent blogger named Sarah Lacy tweeted at TechCrunch Disrupt: “jason goldman = probably least known guy on the panel but best comments!” PandoDaily, the venture-backed site Lacy operates, has covered Twitter and its founders widely. But with the exception of two guest posts by Branch’s Miller, Goldman has never been mentioned in its pages.

The trend isn’t lost on Goldman, a voracious consumer of news. “The industry’s very focused on telling hero narratives,” he told me. It’s not that I think that it’s bad for people to have a public persona. The part that I think is damaging, or unhelpful, is when it seems like there are these visionary C.E.O.s who come up with genius ideas, and then it’s just building a team that allows for those ideas to come forth into the world.” Williams tends to agree. “I don’t want to say founders are overrated, but there are certainly a lot of people who are underrated. And Jason was definitely in that camp,” he said. One recent article, on PandoDaily, seemed to especially pique Goldman. It was by Bryan Goldberg, a founder of the Bleacher Report. “Losers exist,” Goldberg wrote. “Don’t hire them.” Replying on Twitter, Goldman said, “There’s something provocative but contentless about the term ‘loser.’ Approaching hiring as ‘find the winners’ doesn’t work, IMO.” If anyone should know, it’s Goldman.

There’s a lot of talk these days of a second Internet bubble. Facebook has declined in value by over thirty percent since its I.P.O. Of six tech companies worth over $5 billion that went public recently, only Google has increased in market price since. The fate of the tech industry may well rest on a pair of fluttering wings. “When Twitter eventually goes public, it will be carrying the weight of the entire consumer Internet sector on its shoulders,” says Fortune. The Wall Street Journal’s Dan Berman is sanguine about Twitter’s fate, arguing that Facebook’s offering “was a reminder of Silicon Valley’s worst tendencies — the way its culture can force a collective, unquestioning belief about what things are worth.”

One of the entrepreneurs who weathered the last bubble was Evan Williams. At the time Goldman was applying for jobs, Williams was working out of a warehouse in the nearby SoMa district on a suite of publishing tools called Blogger. His office was littered with odd furniture from shuttered startups. It was a scrappy operation. One of the office tales that later impressed Goldman was when Blogger was hacked, on Christmas Day in 2001. Williams, the story goes, was home in Iowa, and spent the holiday in a Kinko’s, running the site off a 28k modem. By 2003, Blogger had managed to attract a million users. When their office manager quit, Williams had two criteria for his replacement: no more Jasons (there were two already), and preferably a woman. Jason Sutter, the St. Louis transplant who now worked for Blogger, suggested someone who fulfilled neither stipulation.

Vastly overqualified for the role, Goldman was nonetheless enthused by the opportunity. In the narrow world of Internet celebrity, Williams was, in the vein of Dave Winer, Tim O’Reilly and Anil Dash, already a well-known figure. Blogger’s newest headquarters, on Market Street, reminded Goldman of a detective’s office, with its frosted glass door and closeted sink and mirror. Williams seemed preoccupied, and Goldman soon found out why: Google, then a 600-person company, wanted to buy Blogger. Technology acquisitions accrue mountains of paperwork, and the methodical Goldman made himself indispensable. “He slipped into being Ev’s right-hand man very quickly,” said Sutter. When the deal went through, there was some question as to whether Goldman would stay on. But among Google’s sea of PhDs, Williams noted, Goldman was Blogger’s only employee with an Ivy League education.

In Mountain View, Googlers were divided between two buildings: engineers, along with Sergey Brin and Larry Page, sat in the Googleplex, while the AdWords team worked separately in the Moneyplex. Blogger was relegated to the money-making hub, in a windowless conference room called Drano. Like Google Reader, another misfit being developed by Chris Wetherell, Blogger was resource-starved and suspect in the search-dominated behemoth. Pretty soon, Williams, a serial entrepreneur, grew weary of the climate. He signaled that Goldman, who by then had slipped back into a product management role, would become his successor. “He was able to do more and more stuff,” remembers Williams. “I don’t think I would have felt that I could leave, except for Jason. I had confidence that he could really man the product, and continue to fulfill the vision that we had worked on.”

With Google’s imprimatur, Blogger grew to 20 million users and a team of twenty. But its content, sometimes racy or revealing, raised hackles in the AdWords department when advertisers bristled. By 2006, the quarrels escalated into a “straight-up turf war,” Goldman said. The battle royale pitted him against Sheryl Sandberg, then the AdWords chief (and now the highly visible COO of Facebook), with Eric Schmidt and Page serving as judge and jury. “It’s been in his nature to shy away from conflict,” Sutter said. “But that was something where he knew they were wrong. Really wrong.” Free speech had long been important to Goldman (Anna Utgoff, from Princeton, remembered an impassioned speech he used to make, about shining the light of truth on evil to make unjust beliefs go away). Although he won the day, Goldman soured on Google.

If that was the push, the pull came from Williams. By then, Williams had partnered with Biz Stone, who came to Google through another acquisition. Their podcasting company, Odeo, foundered when Apple entered the market. Williams instructed his team to return to the drawing board. One of their promising engineers, Jack Dorsey, had as a boy been interested in the intricacies of urban transit. With help from Stone and another Odeo engineer, Noah Glass, he built a barebones site called Twttr. “What if you could share your status with all your friends really easily, so they know what you’re doing? But you don’t want to have to write a whole blog entry or Live Journal entry,” Stone explained the concept in an interview.

That spring, Goldman urged an impromptu trip to Las Vegas on a few Googlers past and present, Williams among them. Ev was playing coy about Twttr, since Google had just acquired another mobile startup called Dodgeball. In Vegas, he pulled back the kimono, and Goldman was immediately hooked. “In my room at the bellagio. Desert mountains are rocking it!” he tweeted. Soon the gamblers were airing their fortunes in real-time (at least when they landed in the black). And by early the next year, Goldman came aboard the fledgling company.

The Vegas trip, with its incessant, chummy updates, would prove an instructive preview. The following March, Twitter — for $7,500, a bird enthusiast sold them the vowels — lit a fire under the South By Southwest conference in Austin, recording 60,000 Tweets each day. Soon the story was of so-called hockey stick growth. Today, its success there is held up as a template for rapid user adoption. Twitter won the award that year for “Best Blog,” and Goldman was starstruck by presenter Ze Frank. “Of course everyone immediately Twittered that Twitter won, causing massive waves of SMS notifications throughout the ballroom,” wrote the Laughing Squid’s Scott Beale. Even so, Twitter flew under the radar for another two years. Only after Ev joined Oprah, in 2009, did Jon Stewart declare a “Twitter Frenzy,” Slate release a parody video, and Twitter become the country’s third-largest social network, behind MySpace and Facebook.

Jason Goldman and Ev Williams in front of the Twitter display at SXSW 2007. Photo courtesy of

Nowadays, such a long period of quietude would be fatal for a startup. The meteoric rise of companies like Zynga, Groupon and Facebook has bequeathed a glut of aspirational apps, and a growing pool of investors who will fund them. But when it comes to writing bigger checks, venture capitalists are increasingly parsimonious. Of these subsequent investments, a Forbes contributor writes, “Series A rounds have flat lined, while earlier funding rounds have flooded the market, leaving thousands of startups floundering for follow-up funding.” Investors jostle to back talked-about founders like young D’Aloisio, but balk at reupping in maturing companies. Looking back to Twitter’s own early metrics, Goldman acknowledged, “It probably would have had the Series A crunch problem.”

At the root of one crunch is another squeeze for talent. With easy money and ample clout available, why work for somebody else? The abundance of seed money, Napster founder Sean Parker said, “results in a talent drain, where the best talent gets diffused and work for their own startups.” The result is a thousand flowers, blooming but flimsy. And the “dirty secret,” as one failed founder admits, is how many of them wilt; or in his words, “die with a whimper.” After his stints at Google or Twitter, Goldman could easily have raised millions to fund his own idea. “To me, the goal is not about role per se,” Goldman told me. “It’s about the team and the idea.” Instead of starting up, he dug in.

This summer, an august group of product managers hashed out on Branch whether theirs was a dying vocation. The prompt came from Ted Barnett, a former product manager at Aol and Apple. “Even in my old ‘waterfall’ days, I argued that good product managers should make themselves ‘invisible,’ Barnett wrote. Now he wondered if they should become extinct. The opposition was hardly full-throated. Goldman branded his profession “internal marketing and internal PR,” while a former Zynga developer said he’d experimented without P.M.s, and the “result was not a disaster.” Not even the product guys made a good case for their kind.

You can point fingers at investors with eyes bigger than their pockets, quixotic founders, obsequious reporters or product managers who don’t speak up enough. Ironically, one of the biggest culprits may be Twitter itself. In the Web 2.0 days, Internet celebrity carried only so far as its nascent conveyors. Social networks gave the web a cosmic jerk. Bloggers, once obscure, accrued retinues as numerous as any movie star’s; one report suggested only 20,000 users generate half of all tweets. “There was a period of time where it was very much the darling of just the Internet set,” Goldman said of Twitter. “But I never wanted it to be something where it was like you had to be in on the joke to understand it.”

That’s a criticism sometimes leveled at Branch, his new startup. Formerly known as Roundtable, the site is engaging, well-designed but vulnerable to charges of exclusivity. One recent Branch included the Awl’s Choire Sicha, blogging pioneer Jason Kottke, BuzzFeed Longform Editor Steve Kandell. It was a lively discussion on the economics of freelance writing, where only notable ones were invited to participate. On another Branch, a contributor worried that sites like Medium “aim high and mean well, but unconsciously create pockets of elitism about content.” But Goldman has high hopes for Branch. “The ultimate goal is that everyone feels enticed to have their own conversations,” he told me, where it’s “not purely a chance for the ninety-nine percent to consume the one percent.”

In his own life, Goldman, too, is reconciling some of the friction between Internet stardom and actual celebrity. Moving to New York may have been one step, and sitting for a profile another. Utgoff, the college debater, thought back to Goldman’s bit on free speech. “There was some point during the Arab Spring, when Twitter became a big part of that, where it clicked in my head,” she said. “Jason actually became part of building that light of truth.” It made him uncomfortable for her to put it that way. “He really does refer to himself as a failed astrophysicist,” said Stone. “It’s like a legit version of a humblebrag.” Still, Goldman said he prefers a quiet dinner for four to a cocktail party. I learned to take him at his word when, that very night, I saw him with three friends at Apiary, a restaurant on Third Avenue. I think he suggested we order the white bean soup, but it was a little too loud to hear.

Although he’s no longer employed by Twitter, Goldman said it endures as a source of daily inspiration. In keeping with his dispassionate bearing, he said the extraordinary moments register just the same as the quotidian. “The experience of NASA using Twitter to talk about the Mars Rover is as amazing to me as seeing Arian Foster, the running back for the Houston Texans, using Twitter to try and reach Neil deGrasse Tyson,” an eminent astrophysicist who taught at Princeton. “All those experiences feel equally intimate and amazing to me. They’re scale-free in the sense that they’re not dependent on the number of zeroes that go behind the people on the system.”

One day last month, a moment arrived in the person of April Underwood, a product manager at Twitter who had been battling a cold. Under the heading, “A 6 second study on product management,” Underwood posted a video of herself picking up donuts at 7:30 in the morning. That day, her team was unveiling a new API for Twitter Ads. Her dedication made Goldman emotional. “Startups are run by people who do what’s necessary at the time it’s needed. A lot of time that’s unglamorous work. A lot of times that’s not heroic work. Is that heroic? Is that standing on a stage in a black turtleneck, in front of 20,000 people talking about the future of phones? No. But that’s how companies are built. That person who did that for the iPhone launch at Apple, we don’t know who he is. All we know is that Steve Jobs came up with the iPhone. But he didn’t ship it. The person who bought the donuts did.”